A Generational Collapse: Tracking the Toll of Trump’s Humanitarian Aid Cuts

In 2025, the global humanitarian system experienced a generational funding collapse.

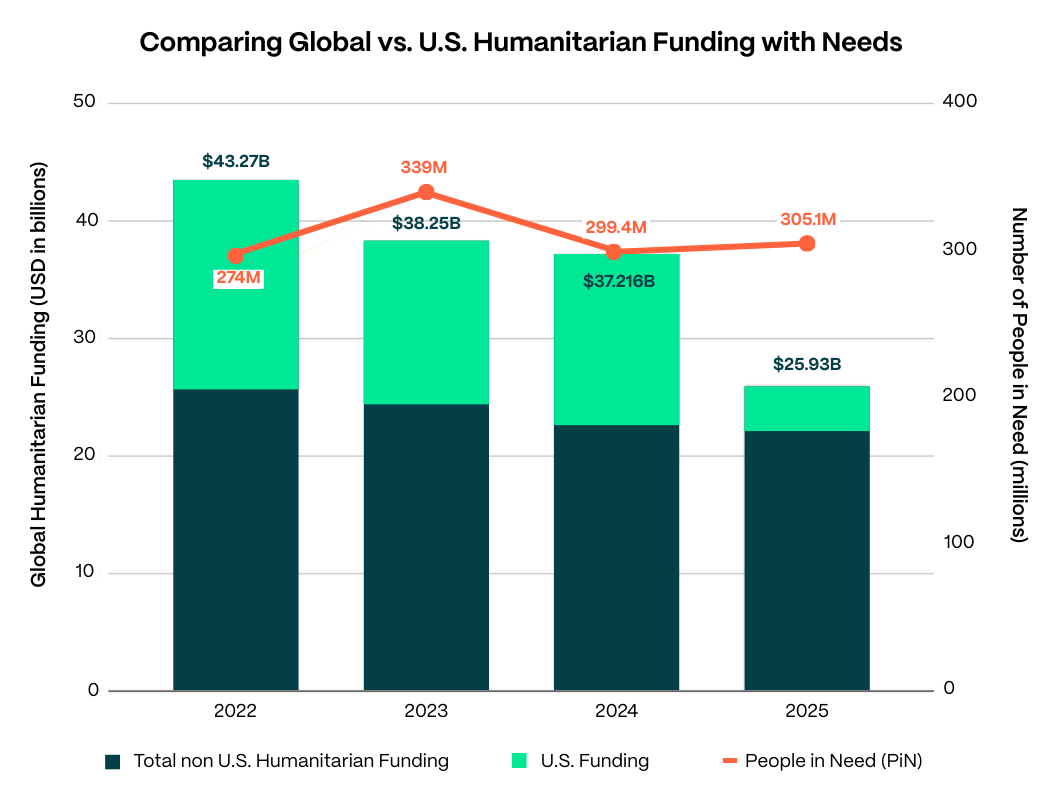

Between 2024 and 2025, more than 30 percent of global humanitarian funding disappeared–driven largely due to an implosion of U.S. support, which fell from approximately $14 billion to $3.7 billion. Following the U.S. cuts, other donors further reduced support, although their reductions were more modest. While global humanitarian resources had already been declining steadily from 2022 through 2024, the most recent cuts marked a far sharper drop. The net effect is that, by 2025, funding totals stood roughly 40 percent below 2022 levels, even as overall humanitarian need largely held constant. The consequences have been deadly and devastating and are now beginning to come into focus.

Following the U.S. freeze on global aid in early 2025, the UN led a “hyper-prioritization” exercise to reallocate limited funding toward the highest-risk needs across major crises. The UN prioritization exercise cut back services and narrowed the number of people targeted for humanitarian assistance to just 88.2 million – a reduction of more than half of the population it planned to target in its initial 2025 Global Humanitarian Overview. UN Humanitarian Coordinators were forced to use “cruel math” to define country-specific priorities and determine which humanitarian interventions should still receive funding. Even these efforts to provide the bare minimum to people with critical needs were underfunded, with humanitarian responders short by more than $3 billion at the end of 2025 to deliver these prioritized plans.

These reductions also substantially reduced the capacity of aid organizations themselves. Major UN agencies abruptly cut thousands of staff, closed field offices in crisis zones, and shuttered programs. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) reportedly cut 5,000 positions and scaled back 185 field offices; The World Health Organization (WHO) slashed more than 2,300 positions; the World Food Program (WFP) eliminated 6,000 positions, and thousands of other staff lost their jobs across other agencies. Among major international NGOs, which implement much of the field level delivery of programs, the impact was similar if not greater. U.S.-funded NGOs hemorrhaged staff, many cutting a quarter to half of their workforce and closing out numerous field programs; one source tallied more than a quarter million positions eliminated globally across all USAID partners.

The net effect has been a historic implosion of global humanitarian response. This brief provides a snapshot of some of the major observable humanitarian impacts of that implosion. The evidence compiled here makes clear that aid cuts are driving elevated mortality, even as the full scope of this mortality remains hard to comprehensively capture and attribute solely to reduced funding. The lethal consequences are visible, and individual instances attributable to humanitarian aid cuts have been persuasively documented.

It is difficult to formulate a comprehensively accurate picture of the overall mortality effects of the aid cuts. Funding reductions have eroded humanitarian data collection: when clinics shut their doors – as more than 2,000 have – they can no longer collect data on lives lost as a result. While Refugees International has not identified abrupt spikes in mortality rates in available humanitarian reporting, this partly reflects an absence of evidence rather than evidence of absence. The most that can be confidently said is the humanitarian funding cuts are already costing individual lives across multiple crises, while larger-scale mortality impacts beyond the most vulnerable groups remain unclear.

These apparent mortality patterns may indicate that the UN’s “humanitarian reset” exercise last year was helpful in blunting the immediate risks of elevated mortality. But the same data also indicate, ominously, that people living in humanitarian crises are broadly reverting to precarious survival strategies in order to stay alive – or what humanitarians refer to as “negative coping mechanisms.” Forcing desperate parents to choose between feeding or educating their children is unconscionable. This is not a sustainable situation: negative coping strategies can defer a spike in mortality only until people exhaust those coping mechanisms. So while the timeline for large-scale fatal impacts may be lengthened, the fundamental trajectory still risks hundreds of thousands of people dying from aid cuts as these conditions persist.

The collapse in international humanitarian funding also reflects an apparent erosion of global political support for humanitarian action. The Trump administration’s closure of USAID is the most prominent manifestation of this, but the trend is broader. Aid budgets in many countries have declined as rising nationalism is turning governments inward, reducing political support for global solidarity. These trends raise daunting questions: Will humanitarian funding ever rebound? If not, how many will die as a result?

Methodology and Scope

This analysis draws on publicly reported humanitarian impact data, Refugees International’s own field reporting, and reporting from refugee-led organizations and community-based NGOs in multiple crisis-affected countries. It is not an exhaustive catalog of all impacts, although such an exercise will be critically important as more data continues to emerge.

The task of gathering data is complicated by the aid cuts themselves. The cuts have triggered a sharp decline in data collection and monitoring of key humanitarian indicators. As USAID programs have disappeared, so have their reporting requirements designed to track improvements to beneficiaries’ wellbeing. Further, routine data collected at health facilities on the prevalence of disease, acute malnutrition, and vaccination rates are much more difficult to collect due to the closure of thousands of health facilities and layoffs of trained healthcare professionals. In early 2025, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) program, which collected household-level data and key health indicators, had its U.S. government funding slashed. Additionally, as part of the withdrawal from the WHO, U.S. funding for information management in health clusters across humanitarian settings vanished.

Main Findings: Fallout from Trump’s Aid Cuts

1. Severe damage has been done to health services in crisis settings.

The WHO estimates that foreign aid for global health shrunk by 30 percent from 2023 to 2025. It reports that the funding cuts in 2025 disrupted services at 5,687 health facilities across 20 crisis settings, including 2,038 clinics that suspended operations or closed. These disruptions and closures have reduced access to essential health services for an estimated 53.3 million people. They have weakened emergency response and health surveillance as well as immunization, malaria, HIV, TB, and maternal and child health programs. In addition, health facilities in humanitarian crises and refugee settings are shifting to emergency-only care and stopping routine treatment. These kinds of effects have been seen across numerous countries, as illustrated in the examples below.

In Bangladesh, the loss of non-emergency services has impacted more than 300,000 Rohingya refugees according to one NGO estimate shared with Refugees International, including the suspension of Hepatitis C treatments for 7,000 people. There has also been a 24 percent year-on-year increase in skin diseases such as scabies, affecting about half a million people in the Rohingya camps in Cox’s Bazar.

In Afghanistan, more than 420 health facilities have closed or suspended operations, eliminating basic health care services for approximately 3 million people since the termination of U.S. funding to humanitarian organizations. There are reports that one major health facility has recorded a “3–4 percent increase in infant mortality” in the months after the cuts.

In Mozambique, 81 percent of HIV prevention funding came from PEPFAR/USAID. Disruptions have already been linked to a 44 percent reduction in viral tests on children and could lead to a 10 percent increase in HIV-related deaths in the next four years.

In northern Ethiopia, aid cuts have reduced the population’s access to medical services, particularly harming internally displaced people and cutting them off from treatment for HIV and other conditions. Women in Tigray are unable to access critically needed health services for sexual violence, with some pleading to international actors for supplies to support rape survivors.

2. Food aid cuts are increasing the risk of severe hunger.

Reductions in rations and cash support quickly increase the likelihood that food insecurity will rise—especially for populations already dependent on humanitarian assistance. U.S. aid cuts and broader funding shortfalls have pushed many humanitarian actors to reduce the amount of food assistance they provide or suspend operations entirely. In refugee settings, the impact is immediate and quantifiable.

In Uganda, funding shortfalls linked to donor cuts forced the UN to suspend food assistance for 1 million refugees and reduce general food rations by up to 80 percent. These cuts may be contributing to the increased rate of acute malnutrition among refugees in Uganda as UNHCR reports that the Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) rate increased from 5.5 percent at the end of 2024 to 7.7 percent in late 2025.

In Bangladesh, WFP’s planned cuts to Rohingya rations would have been devastating for more than 1 million refugees and would have left people trying to survive on roughly $6 per month. Following intensive advocacy, U.S. funding allowed WFP to stem the extreme ration cuts, but, without further funding, cuts are again on the horizon.

In Kenya, the UN reduced the minimum food basket by 40 percent for nearly 800,000 refugees, sparking protests and unrest in refugee camps, and leading to documented deaths.

In northern Ethiopia, reporting from Tigray describes worsening hunger and deaths from malnutrition in forcibly displaced and other communities already struggling to recover from war, with conditions exacerbated by aid cuts.

In Syria, humanitarian operations were already collapsing in some IDP camps in early 2025 immediately following the aid cuts. Food and water distributions slowed or stopped entirely, increasing the risk of renewed displacement.

In Afghanistan, the termination of U.S. support led to the halt of UN emergency food assistance in May 2025 and a steep drop in monthly reach (from 5.6 million people served in one winter month in 2024 to about 1 million per winter month in 2025). This resulted in rising hunger, acute malnutrition in young children, and the closure of nutrition sites that deliver treatment.

3. The aid cuts are particularly harming women and girls.

Aid cuts have acutely hurt women and girls because the services they rely on are often treated as “non-emergency” and the first programs cut as humanitarian organizations re-prioritize funding. Programs have dramatically contracted, including those supporting gender-based violence (GBV) prevention and response, safe shelter, psychosocial support, and sexual and reproductive health care, as well as the outreach and case management that connect survivors to protection pathways. Further, many of these gender-related programs were deemed inconsistent with the Trump administration’s political priorities, making them especially vulnerable to elimination. The impact has not just resulted in fewer services but also weakened referral networks and reduced the number of safe points of contact, increasing household stress and pushing women toward negative coping mechanisms (see section below).

In the Tigray region of Ethiopia, aid cuts have significantly reduced the capacity of safe houses for women. As one local women-led organization told Refugees International, the decrease in UNFPA support for services at three safehouses by nearly $900,000 led to a reduction in survivor intake from approximately 200 survivors to approximately 90 survivors per quarter. Staffing was reduced from 29 staff to 12 protection workers, even as the waitlist for women in dire need of support grew.

In Chad, UNHCR is struggling to respond to the health needs of Sudanese women refugees, including new arrivals from El Fasher who have suffered appalling sexual violence. According to a November 2025 UNHCR assessment seen by Refugees International, the agency faces a $7.2 million shortfall for GBV prevention, life-saving services, and safehouses, and is unable to provide dignity kits for the more than 190,000 women, girls, and at-risk individuals in camps along the Sudanese border.

In Afghanistan, aid cuts led to the closure of family health houses and mobile clinics and caused at least 1,700 female health workers to lose their jobs. These closures and layoffs have stripped Afghan women of their primary – and often only – access to maternal, reproductive, and emergency care and have forced women and girls into dangerous travel that has already resulted in preventable deaths. The cuts also dismantled GBV services and women-led organizations, deepening Taliban-imposed gender apartheid.

4. The aid cuts are degrading migration, asylum, and refugee-protection systems in refugee hosting countries.

Despite the Trump administration’s fixation on migration, their aid cuts are actually eroding orderly migration management in transit and refugee-hosting countries. Many states rely on international support for funding, technical expertise, and staff to manage their asylum systems. The curtailment of aid has degraded the operational capacity of national asylum systems—fewer staff, fewer secondments, fewer protection partners, and fewer “front door” services that help people register, access information, and navigate procedures. More broadly, when humanitarian support and protection casework contracts are cut, people are more likely to be stranded without services, pushed into legal limbo, or forced into irregular onward movement, which can put them in greater danger and force them to operate outside the law. These pressures feed back into migration policy: strained systems and shrinking resources may create incentives for governments to impose restrictions on access to asylum and externalize migration management, further weakening protection safeguards and potentially creating greater insecurity for migrants in displacement flows.

Asylum systems in Latin America have been particularly strained. In Costa Rica, UNHCR programming was cut by 41 percent, and registration capacity for new asylum seekers fell by 77 percent. Historically, the system has heavily depended on UNHCR seconded staff, with an 8:1 ratio of UNHCR-seconded staff to support the government’s Refugee Unit. Removing secondments could leave only five Costa Rican government staff nationwide to process asylum claims, including only one in the south.

In Mexico, UNHCR had provided an estimated 46 percent of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR)’s budget during 2021–2023, and in 2024, the United States contributed 86 percent of UNHCR’s $58 million budget for operations in Mexico. Following aid cuts, UNHCR Mexico reportedly lost about 60 percent of its budget, triggering layoffs, four office closures, and reduced activities. Recent reporting has found that the wait for an initial email response to people seeking asylum can take one to four months, and asylum seekers must wait up to one year for refugee status determination interviews. This makes it far harder for displaced people to access asylum there, and elevates the likelihood that they may seek to reach the United States.

5. People in need are resorting to dangerous survival strategies.

When basic assistance and routine services contract, the effects do not stay neatly in the humanitarian system. As families and individuals come under increasing strain, they turn to negative coping mechanisms. Parents skip meals or trade rations to cover medical costs. As options for livelihoods and food decrease, individuals also become more vulnerable to exploitation. Displaced individuals seek dangerous work or take dangerous journeys, often at the hands of smugglers or traffickers. Women and children are particularly at risk. Women and girls are more likely to face GBV or rely on negative coping strategies such as early marriage, transactional sex, or unsafe migration. The U.S. rapid stop-work orders, program pauses, and aid cuts in 2025 are linked to negative outcomes for children, including increased child labor, early marriage, and school dropouts as families struggle to meet their basic needs.

In the camps in Bangladesh, some Rohingya refugees reported weighing dangerous onward movement when volunteer stipends and other assistance disappeared. In the Rohingya camps, verified cases of child marriage and child labor rose by 21 percent and 17 percent in 2025, respectively, compared to the same time period in 2024.

In Kenya, highly vulnerable families have struggled to meet their food needs because the merchants stopped extending them informal credit after the aid cuts were announced. This forced families deeper into negative coping mechanisms like selling off assets. In Afghanistan, families are resorting to harmful strategies beyond debt and asset sales. One “common strategy” is for women to reduce the amount of food they consume, prioritizing food for the males in their families. Of deep concern is the fact that early and forced marriage and transactional sex are on the rise.

6. Local leaders across crises have been negatively affected by foreign aid cuts but are stepping up to meet the moment.

The aid cuts are hitting local and national responders in the most direct way: they lose the small, flexible funding that supports basic operating costs: staff time, local transportation, communications equipment, and rent. Unlike international actors, local organizations do not have an “exit” option. They are rooted in place, accountable to neighbors, and expected to keep showing up whether or not the formal system is functioning. This is shifting responsibility downward as higher-level capacity shrinks.

In Sudan, in the immediate wake of the aid cuts, some 70 percent of the more than 1,400 community kitchens across Sudan were forced to shut down. Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs) and other local Sudanese actors are sustaining most frontline assistance and protection support across Sudan.

Similarly, in Afghanistan, women-led organizations have been decimated by U.S. aid cuts. In an environment severely restricted by the Taliban, these organizations were often the sole provider of services for women and girls. However, as a result of the aid cuts and Taliban prohibitions, most of these organizations are ceasing operations or are being forced entirely underground, making it harder for women in need to access critical support.

In Ukraine, NGOs, volunteer networks, and local civil society have taken on more while receiving less, scaling up informal social protection, emergency relief, and winterization efforts, even as many face layoffs and curtailed operations due to funding shortfalls. Yet, in the face of escalating conflict, displacement and deepening hardship, these local efforts cannot fully substitute for the breadth of lifesaving services the United States once supported.

Conclusion

As harmful as the impacts this year have been, the worst is likely yet to come. As systems break down further and negative coping strategies run out, levels of unmet need will rise even further. The negative coping patterns playing out across many crises mirror how communities often adapt in the period preceding a famine. Widespread mortality is the endpoint of a famine, but it follows a period in which deprivation spreads, support systems break down, and dangerous survival strategies eventually run out of steam.

The United States and other donors have it within their power to prevent those outcomes – but only if they take swift action to reverse the draconian cuts of the last year.