After the Coup: Burkina Faso’s Humanitarian and Displacement Crisis

Summary

Burkina Faso is now the epicenter of the Central Sahel’s rapidly deteriorating displacement and humanitarian crises. Clashes between armed groups—many with affiliations to the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda—and national security forces and attacks on civilians by all warring parties continue to cause widespread displacement and massive humanitarian need.

Since 2018, violent clashes have internally displaced more than 1.8 million people—a 62 percent increase in the last year alone. Out of Burkina Faso’s 20 million citizens, one in five Burkinabès requires emergency assistance. At present, more than 2.8 million people are food insecure, and this number is expected to rise significantly over the coming months as the country braces for a longer dry season. Yet the country’s humanitarian crisis gets little international attention.

Armed non-state actors, national forces, and pro-government volunteer fighters have been repeatedly accused of committing atrocities against civilian populations—including murder, rape, torture, and violent persecution based on ethnic and religious grounds (primarily targeting the country’s Fulani Muslim minority).

In January 2022, dissatisfaction with the government’s inability to quell the threat of armed groups led a group of mutinous soldiers to overthrow President Roch Kaboré. A few weeks later, coup leader Lieutenant-colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba was inaugurated as the transitional president. He announced that the military transition would last until March 2025 and then formed a new government.

The international community has largely condemned the coup d’état. However, most citizens appear to have either celebrated the change in leadership or resigned themselves to accept it. The coup marked a major step back for Burkina’s already troubled democratic and governance institutions. Furthermore, the military’s history of human rights abuse against ordinary citizens raises serious concerns about what the coup could mean for the protection of civilians in the next phase of the country’s conflict. The coup should be condemned, and efforts made to move toward governance that better reflects the will of its citizens and provides them with adequate protection.

However, in the immediate term, the change in leadership may provide some opportunities to address the humanitarian crisis. There has been cautious optimism about the transitional president’s expressed commitment to addressing the crisis and the appointment of the new Minister of Humanitarian Affairs Lazare Windlassida Zoungrana. The latter is a former head of the Burkinabè Red Cross and is known for being a staunch supporter of humanitarian action.

Immediate international diplomatic and donor engagement is needed to mitigate the consequences of the worsening crisis and to push the new government to better protect and provide for Burkinabè civilians. A useful metric of success will be the government’s compliance with the terms of the African Union’s Kampala Convention—the continent-wide convention on state obligations to uphold the rights of internally displaced people (IDPs). Burkina Faso ratified the convention but has yet to implement its terms.

Unfortunately, donor engagement has failed to keep up with humanitarian challenges. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will likely exacerbate the shortfall of donor funding and food insecurity across the Sahel. One major concern is the risk that financial support will be diverted from ongoing crises like Burkina Faso to the Ukrainian crisis. In addition, more than a third of Burkina Faso’s grains are imported from Russia and Ukraine, and many analysts expect a global shortage and a sharp increase in the basic price of grains. Faced with this reality, aid organizations must be prepared to improve the effectiveness of their work by better researching, planning, and coordinating their efforts.

To head off the worst, the transitional government and donors must support and bolster the work of United Nations humanitarian agencies, as well as national and international non-government organizations (NGOs) to avoid unnecessary and dangerous gaps in the humanitarian response.

Recommendations

The transitional government of Burkina Faso must:

- End violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law. National authorities must denounce abuses and transparently investigate allegations of violations of international human rights and humanitarian law by members of its military and police force and the state-assisted volunteer fighters.

- Cease targeted attacks on the country’s Fulani community by national security forces. Years of government neglect of this minority group have left them vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups that prey on their grievances. Government forces have indiscriminately attacked Fulani civilian communities—wrongfully painting all Fulani as extremists. The attacks on these communities must cease.

- Fulfil its obligations under the African Union’s Kampala Convention. Burkina Faso has failed to live up to the principles and commitments of the convention—the continent’s main legal framework for the protection of IDPs—despite ratifying the Convention. The new Minister of Humanitarian Affairs, Lazare Windlassida Zoungrana, should be tasked with implementing the terms of the Kampala Convention. To this end, Burkina Faso must guarantee unrestricted humanitarian access and allow aid groups to adhere to humanitarian principles. The transitional government must also acknowledge and assist displaced people in Ouagadougou, allow IDPs to receive aid before being registered, and ensure that military operations do not unnecessarily fuel displacement.

UN agencies and humanitarian organizations must:

- Engage and pressure the authorities to improve the protection of and provision of basic services to Burkinabè citizens and guarantee humanitarian access to those in need.

- Collect more detailed information on the push and pull factors of displacement. This information helps humanitarian actors to understand the reasons for displacement, project trends, and plan programming. This information could be collected using existing data collection and dissemination platforms such as the Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM).

- Ensure that cluster leads and co-leads increase their analysis of the humanitarian situation. More in-depth evaluations of needs, trends, and critical gaps by sector of the response will help relief groups to coordinate within the cluster to allow better coverage of needs and decrease programmatic overlaps.

- Conduct frequent intention surveys of displaced communities. Collecting and sharing this data will allow organizations to understand if IDPs hope to return to their areas of origin, security permitting, or if they prefer local integration or relocation as long-term solutions to their displacement.

Donor governments must:

- Increase, or at a minimum, maintain current overall funding levels for aid. Despite global competition for funding, donors must not disengage as the humanitarian situation in Burkina Faso continues to deteriorate.

- Act quickly to provide funding for food assistance. With food security rapidly deteriorating in the coming weeks and months, donors must act quickly to provide the resources needed for aid groups to mitigate the consequences of national food shortages.

- Support the localization of the response. Engaging in dialogue with national NGOs, donors, and international aid agencies can help local groups learn more about donor standards so that they can play a more active role in the response. International partners should then support their capacity-building efforts to meet these standards.

Research Overview

A Refugees International team traveled to Burkina Faso from February to March 2022 to assess the impact of the country’s recent coup d’état on the deteriorating humanitarian crisis and the effectiveness of the aid response. Team members conducted interviews with representatives of UN aid agencies, foreign embassies, and local and international non-governmental organizations.

Background

Since the onset of Burkina Faso’s security crisis in 2018, the country’s humanitarian challenges have steadily worsened. Violence, need, and displacement have spread to every administrative region of the country. When Refugees International last traveled to the country in September 2019, 289,000 Burkinabès had been displaced by violence. The latest figures now estimate that more than 1.8 million people have been forced to flee their homes and 3.5 million require humanitarian assistance.

Burkina Faso was once known for its peaceful coexistence between ethnic, religious, and linguistic groups, but the ousting of former President Blaise Compaoré in 2014 left a power vacuum that destabilized the country. Although President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was democratically elected in 2015, insecurity continued to worsen. This allowed for militant groups like Ansarul Islam to form and for offshoots of the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (referred to as JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara to spread into the country from neighboring Mali and Niger. In 2018, instability began to cause widespread displacement and tipped the country into a humanitarian crisis.

Rebel factions, state-supported self-defense groups, and national forces have repeatedly looted and attacked villages. Rebel groups continue to systematically damage or destroy health and education infrastructure, increasingly using improvised explosive devices, and executing those they believe to support the government. The security landscape was further complicated in January 2020, when the country’s parliament passed the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland act to support the thousands of local self-defense groups created during the crisis. This program offers volunteer fighters a brief two-week training session, after which they are given communication devices and weapons to fight in their regions of origin against armed factions.

As detailed in Refugees International’s last report on Burkina Faso, civilians not only face atrocities from armed non-state actors, but also from national forces and pro-government volunteer fighters. Reported atrocities committed by all parties to the conflict include murder, rape, torture, and violent persecution based on ethnic and religious grounds. Muslim Fulani communities are disproportionately attacked by all warring parties. This Muslim ethnic group, which spans across Africa, is a minority group in Burkina Faso and has long been excluded from power and neglected by the government. They live along the country’s northern borders with Mali and Niger—the center of the violent crisis. Extremist groups disproportionately recruit young Fulani men, taking advantage of the dearth of economic prospects and government services in their communities to get them to join their ranks. As a result, an erroneous belief has spread that Fulani civilians are responsible for many of the terror attacks. This has left them vulnerable to attacks from state forces. But similarly, armed groups attack Fulani communities when they do not support the rebels.

As the government struggled to contain the spread of violence and respond to mounting humanitarian needs over the last two years, former President Roch Kaboré censored journalists, restricted access to displacement camps, and hindered the aid response by intimidating and suspending aid groups. Frustration with the government’s actions began to mount. Some citizens criticized the government for not taking a stronger stance against armed groups. Others called out the deterioration of democratic norms and institutions, and widespread human rights violations. Many people took to the streets to show their frustration, and the government responded by banning anti-government protests. Two days later, on January 23, 2022, a group of mutinous soldiers detained the president and forced him to resign the following day. At the time of writing, Kaboré is still being held by the army.

On February 16, 2022, Lieutenant-colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, who led the coup, was sworn in as president. He subsequently announced that the transition back to civilian leadership would take place 36 months later (March 2025). At the end of February, he announced the members of his new government. The appointment of Lazare Windlassida Zoungrana, former head of the Burkinabè Red Cross, as Minister of Humanitarian Affairs is cause for cautious optimism that the tense relationship between the government and aid groups could be a thing of the past.

Reactions to the military takeover of power have varied. International stakeholders like the African Union, United Nations, and French and American governments have all publicly opposed the coup. For its part, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has strongly condemned the coup and announced that economic sanctions would be imposed if civilian leadership was not restored by April 25, 2022. These sanctions could impact the country’s economy and ability to import food stocks, which will exacerbate the country’s already dire humanitarian crisis.

Perceptions on the ground have been quite different. Although pro-putsch Burkinabès took to the streets in Ouagadougou to show their support, areas beyond the capital—especially areas that have been badly affected by conflict and violence perpetrated by the state forces—have been less welcoming of the change. As a Fulani aid worker explained, “now those who attack my people with impunity have even more freedom to do so.” While many Burkinabès may not endorse or support the coup, most appear to have reluctantly accepted the new government.

While it is too soon to say if the change in leadership will lead to a more positive approach to the humanitarian situation from the government, the security and humanitarian crises have continued to deteriorate. According to aid workers, security incidents dramatically increased over the course of the last months of 2021 and in early 2022. According to the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), there was an 11 percent increase in security incidents in February 2022 compared to the previous month.

Humanitarian staff said that rebel groups have responded to the military’s takeover by increasing their attacks on both civilians and military targets. Armed groups have been destroying water points, cell phone towers, and electricity infrastructure. They have encircled and blockaded towns across the northeast of the country, like Djibo and Titao, stopping the flow of people and necessary goods in and out of these locations. The use of explosive devices by insurgent groups has also increased and are believed to have killed over 300 people.

The new regime has signaled its intent to increase security operations. Given the armed forces’ history of disregard for civilians and human rights, a new round of military operations could have devastating consequences for civilian protection and humanitarian needs more broadly. As the head of a national NGO told the Refugees Iternational team: “focusing solely on security won’t work.” The transitional government must simultaneously improve governance, provide for and protect the civilian population, and allow aid groups to fill critical gaps in basic service provision.

The Humanitarian Crisis

The country is facing the region’s largest protection crisis. Civilians are at risk of violations that include physical violence, torture, gender-based violence, arbitrary arrest and detention, and restrictions on freedom of movement. Burkina Faso’s displacement trends are unique in that most IDPs report having only fled when faced with immediate danger, and not in anticipation of violence. A REACH survey found that in Burkina’s Sahel1 region, the most affected of the country’s administrative regions, 91 percent of IDPs indicated that direct violence was their primary reason for displacement.

Aid groups are struggling to meet the ever-growing needs of civilians. A humanitarian worker complained that the international community “glorif[ies] the fact that IDPs are being welcome by host communities, but we should be embarrassed that IDPs are [having to find] assistance among host communities who similarly struggle to have their basic needs met.” The aid worker explained that “this is a sign of a failing humanitarian response” where the displaced cannot rely on the government or the aid community, and that neither they nor the host communities are getting the assistance they require.

The deteriorating security environment limits humanitarian access where it is needed most. Gaining access is incredibly difficult and labor intensive to negotiate. Humanitarian staff with whom Refugees International spoke explained that they must repeatedly negotiate access every time they wish to enter a specific location. The dynamic security landscape and recent changes in government mean that aid workers must constantly build rapport with new interlocutors to reach communities. Even when access is granted, relief groups are still subject to threats, robberies, abduction, or violent attacks. An aid worker told the Refugees International team that the frequency of such incidents had increased over the course of 2021.

As a donor told the Refugees International team, “this is a protection crisis that was only made substantially worse by the previous government’s heavy-handed response.” The new regime will have a long road ahead to address some of the most pressing needs. As of early March 2022, 3,683 schools have been forced to close because of insecurity. Nearly 600,000 children have been left without access to schools. As of the end of February 2022, 160 health centers have closed. IDPs, civilian populations, and host populations continue to pay the highest price for the increase in violence. Less than half of those receiving humanitarian assistance report that help comes when they need it.

Food Insecurity

In recent years, violent conflict, resource scarcity, COVID-19, and droughts have worsened food insecurity. At present, 2.8 million people, more than 10 percent of the total population, are currently food insecure in Burkina Faso, and this number is expected to rise significantly over the coming months. Although the yearly lean season usually lasts from June to August, it is projected to begin in April in 2022. This longer dry season, coupled with rising violence, will deplete the availability of food for millions. This will only increase the number of food-insecure people across the region. At present, there are an estimated 323,000 people who are in IPC Phase 4 (critical), one phase below famine on the Famine Early Warning System’s Integrated Phase Classification. By the summer of 2022, this total is expected to double, with more than 628,000 people in IPC Phase 4. Immediate action is required, and as an international aid worker told the Refugees International team, “providing funding for food security in May will already be too late.”

The troubling food insecurity trends will undoubtedly be worsened by the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of wheat, the second most-produced grain in the world. Russia and Ukraine export more than a quarter of the world’s supply of wheat and more than 30 percent of Burkina Faso’s imported supply. As their grain exports decrease over the coming weeks, a global shortage is expected and the basic price of grains will likely sharply increase.

The World Food Program (WFP) has already experienced a worldwide rise in the cost of operations and procurement of $42 million per month due to inflation. WFP now estimates that the Ukraine-Russia conflict will result in a surge of an additional $29 million a month for its costs. On a global scale, this will dramatically augment the funds needed to address food insecurity. In 2021, humanitarian efforts to address food insecurity received just over 30 percent of the required funding. The increasing cost of grain will mean that it will cost aid groups more to provide less food stocks. In Burkina Faso, this will further limit the availability of grain, cause inflation, and lead to intercommunal tensions over scarce food.

Operationalizing the Kampala Convention

On March 1, 2022, transitional President Damiba signed and adopted a new transitional charter for his government. The charter lists the new regime’s principal missions, including providing “an effective and urgent response to the humanitarian crisis and the socio-economic and community suffering caused by insecurity.” An aid worker told the Refugees International team that Burkina Faso is a scene of “human suffering on a massive scale, and it won’t get better, given [the country’s] quick population growth and a weak government, without dramatic change.” This commitment to prioritizing the humanitarian response, however, creates an opening for the international community and aid groups to pressure the government to improve its delivery of services and engagement with aid groups.

The African Union’s Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (known as the Kampala Convention)—the main legal framework for IDP protection on the continent—should be used as the main road map for ushering in these improvements. The Kampala Convention established a shared vision among African Union states of the necessary legal framework for the protection and assistance of IDPs. It lays out the obligations of states in addressing displacement and calls for governments to adopt measures aimed at preventing and putting an end to internal displacement. The Convention is a historic milestone as it is the only legally binding instrument for the protection and assistance of IDPs.

In 2009, the government of Burkina Faso ratified the Convention but both President Compaoré and Kaboré’s governments made little efforts implement it. The latter’s failure to do so was particularly problematic given that the displacement crisis occurred during his years in power. Instead of following its terms, Kaboré’s government repeatedly violated the Convention.

1. Failure to guarantee unrestricted access and allow aid groups to adhere to humanitarian principles set out in the Kampala Convention.

Aid groups, both local and international, indicated that over the last few years, national authorities (civil servants and security forces alike) and government-supported self-defense groups have impeded humanitarian access to areas where armed groups were present or exerted control over territory. In some cases, the government and its allies have even accused relief groups of supporting rebel factions with aid deliveries. Multiple NGOs told the Refugees International team that this had occurred in their efforts to respond to the needs in the city of Djibo. The large city in the north of the country is experiencing dire humanitarian needs as a result of repeated sieges by armed groups, but aid groups reported that government authorities are also preventing aid from flowing into the city to the communities in need.

Relief operations are rooted in the core humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. Based on these principles, organizations must respond to populations in need, regardless of whether these populations are in government-controlled areas or not. The previous government’s failure to respect these principles has been deeply problematic. Changing course would fulfill the Burkinabè government’s responsibilities to “allow rapid and unimpeded passage of all relief consignments, equipment, and personnel to internally displaced persons” and “uphold and ensure respect for the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence of humanitarian actors” under Article V (7) and (8) of the Convention.

2. Refusal to acknowledge and assist displaced people in Ouagadougou

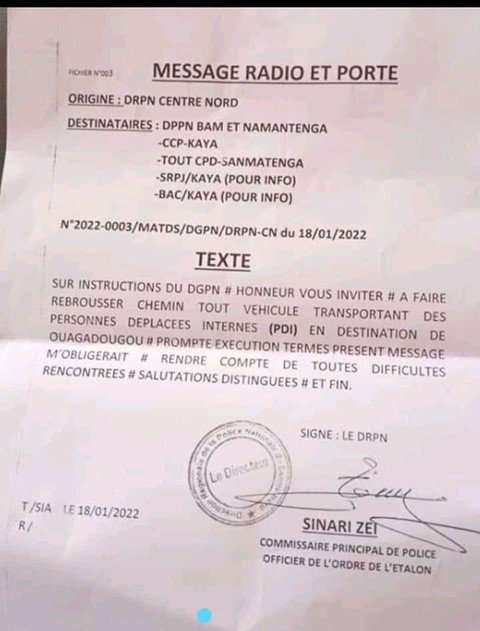

Official government tallies of IDPs in the Centre region—home of the country’s capital Ouagadougou—estimate that 1,051 people are seeking refuge there. Numerous NGOs, however, told the Refugees International team that the total number of displaced people in the capital could be as high as 25,000 and that most are unable to access basic services such as health and education. Under the previous government, there were widespread efforts to deny their presence, and even block IDPs from coming into the capital (see Annex). An international donor told the Refugees International team that “government denial is not only political posturing, but also to avoid having IDPs compete with locals over limited government services available.” The new government should recognize that by ceasing its denial and allowing IDPs in the capital to be officially counted and registered, aid groups would be able to provide aid to these communities.

This ongoing denial is a violation of the Kampala Convention, which under Article IX (2, b) calls for State Parties to “[p]rovide internally displaced persons to the fullest extent practicable and with the least possible delay, with adequate humanitarian assistance, which shall include food, water, shelter, medical care and other health services, sanitation, education, and any other necessary social services…” If the government is unable to provide basic services to these populations in need of assistance, it is of paramount importance that the government publicly acknowledge their presence in the capital and allow aid groups to assist them instead.

3. Denying the right of IDPs to receive aid before being registered

The National Council for Emergency Relief and Rehabilitation (known by the French acronym CONASUR) is charged with counting and registering all IDPs in the country—with the help and support of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). The previous government’s policy of only allowing displaced citizens who were officially registered with the CONASUR to access aid (emergency food distributions, shelter kits, etc.) should end immediately. According to aid workers in the country, the process of registration can take up to a month or more. In 2021, Ground Truth Solutions published a report detailing the experience of displaced Burkinabès who had received humanitarian assistance. According to their findings, only 47 percent of participants felt that they received aid when they most needed it. Aid groups told the Refugees International team that this delay is mostly caused by this rule.

This administrative wait not only delays access to humanitarian assistance to newly displaced people but is also in clear violation of the Convention’s requirement that governments “[p]rovide internally displaced persons to the fullest extent practicable and with the least possible delay, with adequate humanitarian assistance.”

The government of Burkina Faso must publicly allow organizations to provide much-needed assistance before IDPs are formally registered. They must allocate more resources to the CONASUR to allow them to decrease the time it takes to register displaced populations and expand their work across the country as the violence intensifies and presence of IDPs increases in all regions of Burkina Faso.

4. Attacking civilians and fuelling widespread displacement

As detailed above, Burkina’s national security forces, along with their volunteer allies, have been accused of some of the deadliest attacks on civilians—all of which have contributed to the displacement of Burkinabès. Alarmingly, nearly all these attacks have gone uninvestigated and unpunished. The government’s role in instigating displacement is in conflict with the Kampala Convention’s Article IV (1) which requires the State “to prevent and avoid conditions that might lead to the arbitrary displacement of persons.”

While military operations targeting armed groups may cause displacement, the targeting of civilians must stop. Furthermore, the government must investigate accusations of abuses of human rights law and violations of international humanitarian law by members of its security forces and the state-supported volunteer fighters.

New Opportunities

It is both urgent and important that the transitional government break the cycle of disregard for the Kampala Convention and adhere to its provisions. This will not only allow the government to better protect internally displaced people but also help build trust and confidence of the international community at a crucial moment in the country’s humanitarian crisis.

On March 1, 2022, the country’s new ministers were announced. Of all the new appointments, the announcement of Lazare Windlassida Zoungrana as Minister of Humanitarian Affairs is a reason for hope. Minister Zoungrana previously served as Secretary-General of the Burkinabè Red Cross and is well-respected. He has vast experience with international humanitarian law and humanitarian principles. The transitional President should charge Minister Zougrana with operationalizing the Kampala Convention in Burkina Faso.

Implementing a More Effective Response

The international humanitarian response has been significantly bolstered since the Refugees International team was last in Burkina Faso in late 2019. OCHA has increased its footprint across affected regions to coordinate relief efforts, and the Cluster system—the structure responsible for coordinating relief organizations by each sector of the response—has also been established. Despite these improvements, more remains to be done to optimize the response and coordination.

A survey of aid recipients conducted by Ground Truth Solutions highlighted that only 35 percent of those surveyed felt that the aid they received met their basic needs. This low figure can be explained, in part, by low donor support as explained above, but relief groups must do more to improve their contributions. A donor representative lamented that they felt that aid groups—both UN agencies and NGOs—were too cautious and that “their appetite for risk was too low” in their programming and in their efforts to advocate to the government. Multiple donors and an international NGO lamented that many other groups are too often unwilling to leave the capital city and stressed the importance of doing so to share their expertise with staff in affected regions.

Donors and aid groups alike explained that a key way to better the response would be to improve the information on trends related to displacement and humanitarian needs and gaps in assistance. Firstly, organizations explained there was a lack of data on the push and pull factors of displacement for newly displaced people—i.e. the reasons people fled their area of origin or last location, and why they made their way to their current destination. Data is also needed on those who have been displaced more than once. All this information could be gathered through existing data collection projects such as the Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM), jointly led by Action contre la Faim, Solidarités International, Humanity & Inclusion, and the Danish Refugee Council, which monitors displacement and humanitarian programs.

There is also a gap in information on the intentions of populations that have been displaced for longer periods of time. Collecting and sharing such information will afford organizations a deeper understanding of IDPs’ plans to return to their areas of origin, security permitting, or if they prefer local integration or relocation as long-term solutions. This information would help improve response planning and funding allocation.

Furthermore, aid workers expressed disappointment with the lack of analysis being carried out within the individual Clusters—especially at the national level. The Cluster system leads the coordination of the aid response by sector of intervention. In contrast to the underfunded overall response, the coordination system in Burkina Faso is relatively well-funded compared to other crises, theoretically allowing those who lead, and co-lead, each Cluster to be dedicated full-time staff (which is not always the case). This should afford leads and co-leads with time to conduct more analysis of needs, trends, and critical gaps in the response.

Financial Discrepancies

According to OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service, last year’s aid response only received 44 percent of the $607 million required to fulfill the 2021 Humanitarian Response Plan. While this is undeniably too low, the breakdown of where these funds were allocated raises interesting questions about performance. Shockingly low financing levels in most areas of aid delivery stood in contrast to the relatively large sum allocated to coordination. While this figure may include a portion of funds to be disbursed to partner groups, the fact that it is comparatively so much higher than aid delivery sectors is alarming. It is also particularly surprising given that numerous aid workers—from UN agencies, local and international NGOs—as well as international donors bemoaned the lack of analyses provided by OCHA and the Cluster-specific coordination structures.

Although overall funding has increased over the years, it has not kept up with the steady worsening of the crisis and the increasing number of people in need. As a result, the humanitarian response has been underfunded year after year. Given this reality, OCHA’s Humanitarian Response Plan for 2022 has requested a lower amount—$590 million for the year—compared to 2021. A UN staff member explained that this year’s plan is smaller not because there are fewer people in need but, given insufficient international funding, they know they will not be able to provide for them all. Instead, they have a reduced and more tailored plan, but unfortunately, they still may be shockingly underfunded.

As the world’s attention is seized on the Ukrainian crisis, even as needs grow to historic levels in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, and elsewhere, funding for humanitarian aid in Burkina Faso will likely decrease. NGOs in the country have already been warned by some donors that funding for lifesaving operations could be diverted to efforts to address humanitarian consequences of the situation in Ukraine. Of course, Ukrainians in need require donor support, but disengagement from ongoing crises is not the answer. At the very least, donors must maintain funding levels and more equitably balance their funds between sectors within the Burkina response. With food insecurity rapidly increasing, donors must act quickly to support relief efforts to mitigate the consequences of national food shortages.

Improving the Localization of the Response

Refugees International’s February 2020 report on humanitarian needs in Burkina Faso called for aid groups and donors to partner with civil society networks—comprised of hundreds of organizations ranging from human rights advocates to development groups—who were and are still keen to engage in addressing their country’s unfolding crisis. Since then, local groups have played an increasingly large role in the humanitarian response. In June 2021, the Regional Humanitarian Funds for West and Central Africa was launched in the aftermath of the Director-level Meeting co-hosted by OCHA and the governments of Denmark and Germany. The funding mechanism, managed by OCHA, pools together financing from several international donors to respond to the growing needs in the region and emphasizes supporting local actor involvement in the response. By late 2021, a total of $36 million had been pooled, $20 million of which was slotted to fund humanitarian efforts in Burkina Faso to be disbursed over 2022. Despite this positive change, Burkinabè groups remain an under-utilized resource. As funds continue to be distributed over the year, OCHA and donors must prioritize directly funding local organizations, or calling for international NGOs to increasingly partner with national partners.

The Refugees International team met with a dozen national organizations whose representatives explained that notwithstanding this improvement, they still struggle to secure international funding for their activities, despite having more granular local knowledge and access to remote populations. Localizing the aid response—increasing funding for local and national groups in a humanitarian setting—improves cost efficiencies, supports the local economies, and improves the bespoke nature of the response design and implementation.

A member of a national NGO explained that their funding applications are “often denied, citing a lack of capacities, but donors don’t give us feedback on which capacities should be improved in order to receive financing.” Burkinabè organizations asked for dialogue between their staff and international donors. They believe that opening these channels—perhaps by scheduling quarterly meetings—would increase their awareness of what capacities they need to hone and that doing so will eventually lead them to play a bigger role in the response. Moreover, donors should also consider funding these capacity-building efforts, especially when it comes to donors’ financial and activity report standards.

Conclusion

The year ahead will be a challenging year for Burkina Faso. While the political landscape remains uncertain, the country will experience a worsening displacement and humanitarian crisis. The transitional government has a responsibility to protect and provide for its citizens. A starting point would be for the government to comply with its obligations under the Kampala Convention. In order to mitigate the consequences of the dire situation, donors must provide aid groups with the resources needed to respond to the worsening situation and encourage the government to fulfill its responsibilities and do right by its citizens.

For too long, this crisis has not garnered the required attention, action, or funding it warrants. Competing crises, especially with the outbreak of the conflict and humanitarian suffering in Ukraine, will continue to leave the plight of the Burkinabè in the global shadows. Donors and aid agencies must not disengage at this pivotal moment.

Annex

Order from the DGPN (National Police) in command to “turn back any vehicle transporting internally displaced persons (IDPs) to Ouagadougou” from January 18, 2022.

Endnotes

[1] This is an administrative region within Burkina Faso, not to be confused with the broader Sahel region spanning across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Cover Photo: Women prepare maize in northern Burkina Faso. (Photo by Giles Clarke/UNOCHA via Getty Images)