The Fallacy of Control: Tightened Asylum and Reception Policies Undermine Protection in Greece

Introduction

Greece was unprepared in 2015, when it became the primary entry point for more than 1 million people seeking protection in the European Union (EU). With a nascent Asylum Service and no reception capacity, it left people awaiting asylum decisions for months or years in inhumane conditions. Although the EU and United Nations provided financial and operating support, the lack of effective responsibility sharing in the absence of a regional EU approach hindered Greece’s ability to respond. As its economic and social systems strained to accommodate new arrivals, public sentiment and political will soured. Successive governments designed policies portraying refugee reception as a temporary challenge. Seven years later, asylum seekers continue arriving in Greece, but true access to protection remains elusive.

Since 2020, the number of new arrivals, pending applications, and people in camps have dropped significantly. The Ministry of Migration and Asylum (MoMA) claims these figures indicate it has “regained control” of the situation. But they are largely driven by policies and practices that prevent and limit access to protection and dignified reception. On both the islands and mainland, asylum seekers remain confined in increasingly restrictive and securitized settings, marginalized instead of welcomed. The government narrowly delimits displaced people’s access to aid and stymies civil society efforts to help. Even when governmental and non-governmental actors identify common problems and interests, the response often founders. A lack of trust and coordination among stakeholders undermines an effective and humane response, leaving thousands of forcibly displaced people without critical protections.

These measures shape Greece’s long-standing policy of deterrence, containment, and exclusion of asylum seekers and refugees, legitimized by the European Union’s support. The introduction of a restrictive new asylum law and new reception model since 2020 has brought these dynamics into sharp focus. The Greek government—together with EU, UN, and NGO partners, and displaced people themselves—must take this opportunity to assess the changes’ impacts and address harms before further implementation.

Recommendations

To the Greek Government:

- Guarantee asylum seekers’ full access to a fair asylum process, with safeguards for at-risk groups. Ensure the right to territorial asylum. Revoke Joint Ministerial Decision 42799/2021, which wrongly designates Turkey a safe country for asylum seekers. While it stands and Turkey refuses readmissions, re-examine on their merits applications that have been deemed inadmissible. Adequately resource the Greek Asylum Service to process applications in a timely manner without sacrificing due diligence. Train all staff to identify vulnerabilities and refer care at any stage in the asylum process, and facilitate applicants’ access to interpretation and legal aid.

- Provide adequate and dignified accommodation for asylum seekers. Replace the camp model with a decentralized, community-based reception and accommodation system. So long as camps remain, they should serve only as temporary landing points for asylum seekers to promptly register with authorities while having access to essential care and services, including from NGOs. Applicants should then be referred to suitable accommodation where they have support to navigate the asylum process while beginning to integrate into local communities.

- Systematically monitor conditions in new “controlled structures” and apply lessons. Develop a plan to monitor and evaluate conditions in the new restricted-access reception and accommodation facilities for asylum seekers and their impact on residents’ well-being, access to services, and integration. Enable independent actors, including NGOs, to conduct monitoring and provide residents effective channels to provide feedback. Create a mechanism for camp managers to systematically share information with each other and relevant stakeholders to quickly address problems and avoid replicating them elsewhere.

- Ensure the safety of camp residents and staff without infringing on their rights and freedoms. Halt construction of prison-like security and surveillance structures and uphold residents’ freedom of movement. Regularly engage residents and staff to understand their safety concerns and proposed solutions. Increase access to private shelter, lighting, and electricity to prevent gender-based violence and improve safety overall.

- Increase capacity to ensure access to special protections for marginalized groups. Increase capacity to house individuals with “vulnerabilities” outside of camps. Inside camps, establish dedicated safe spaces for children and unaccompanied minors, women, and other at-risk groups. Ensure adequate staff capacity to provide psychological support and manage child protection and gender-based violence (GBV) cases.

- Ensure access to basic means of subsistence for all persons, regardless of their status. Provide all persons residing in state-run or managed facilities, irrespective of their legal status, access to material reception conditions, which include food, housing, and clothing and must be provided under EU law. Quickly and fully compensate all individuals for missed cash distributions owed in late 2021, including those who have since received asylum decisions.

- Adopt an approach to reception that facilitates early integration. Provide asylum seekers in camps with free transportation to urban centers and opportunities for engagement with local Greek communities, including through education, recreation, and employment. Revoke conditions on cash assistance that prevent asylum seekers from living in independent housing.

- Exercise forethought and due diligence to ensure good program management that maintains quality reception conditions. Design a resilient and sustainable reception infrastructure able to respond to changes in demand. Government entities assuming management of key programs and services from UN agencies and NGOs must dedicate the necessary time and resources to guarantee smooth transitions without service disruptions.

- Foster a more constructive operating environment for all stakeholders. Reverse policies that obstruct or criminalize NGOs and humanitarian efforts, including excessive registration requirements. Together with relevant UN agencies, assess existing coordination mechanisms and reform any proving ineffective. Ensure senior government representatives’ active participation in multi-stakeholder coordination meetings. Prioritize coordination to improve data collection and sharing and empower asylum seekers and refugees themselves, as well as NGOs working closely with them, to participate in decision making.

To the European Commission:

- Hold Greece accountable for its mistreatment of asylum seekers at its borders. Trigger infringement procedures against Greece for its breach of EU law. Uphold the demand that Greece put in place a border monitoring mechanism that is independent and adequately resourced, and has the mandate and expertise to ensure fundamental rights and accountability. Condition the release of additional financing for border management on progress in this area.

- Fulfill requests from Members of the European Parliament to assess the compatibility of Greek legislation on the NGO Registry with EU law. The Commission should immediately conduct the requested legal assessment and hold Greece accountable if it determines the regulations governing NGO operations breach provisions of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the asylum acquis.

- Review the Greek reception model and seek alternatives to camp settings. EU support has enabled a strategy of containment and social exclusion of asylum seekers in Greece that risks becoming a model for the rest of the region. To reverse a dangerous trend, EU institutions should explore more dignified alternatives to camp-like structures for registration and community-based reception.

- Continue providing technical and financial support to ensure an adequate response to displaced people’s protection needs. EU funding remains crucial to supporting the Greek government, UN agencies, and NGOs in delivering essential services to asylum seekers. Member States should also share responsibility through a regional solidarity mechanism that includes relocation.

Methodology

Refugees International’s Advocate for Europe undertook a research trip to Greece from November 2-17, 2021. She visited several camps for asylum seekers: the new Closed Controlled Access Centre in Samos (Zervou); the temporary Reception and Identification Centre in Lesvos (Mavrovouni); and the Eleonas, Malakasa, and Ritsona accommodation sites in and around Athens. She interviewed refugees and asylum seekers; Greek and American government officials; European Commission representatives; UN agency representatives; and members of national and international non-governmental organizations.

Access to Asylum

Various policies and practices create considerable obstacles for displaced people seeking protection in Greece. Authorities have physically blocked asylum seekers’ access to Greek territory by building border walls; obstructing maritime search-and-rescue operations; summarily expelling people; and conducting violent, sometimes deadly pushbacks at land and sea. NGOs and journalists have extensively documented pushbacks, which are illegal under EU and international law.1 But although Greece has drawn widespread criticism and dozens of lawsuits, the government simply rejects accusations of misconduct.2

The EU, which largely funds Greece’s asylum and migration response, has not taken meaningful action to hold Greece accountable. In an important but overdue move, the European Commission in September 2021 conditioned the release of additional migration funding on Greece establishing an independent monitoring mechanism to prevent and investigate rights violations at its borders. After initially rejecting the demand, the government appeared to reverse its position in December 2021. But it delegated the role to the National Transparency Authority (EAD), an audit body established in 2019 to counter fraud and corruption. The Commission accepted this, but experts told Refugees International the EAD lacks sufficient expertise and independence to effectively play the role. In evaluating Greece’s progress, the EU should assess the mechanism against criteria established in international guidelines and civil society recommendations.

Asylum seekers who do reach Greek territory then face legal and practical barriers to protection. For years, prolonged processing has caused overcrowding in reception centers and accommodation sites, even as the EU Asylum Agency (EUAA) has provided training and personnel to the Greek Asylum Service (GAS).3 European Commission representatives told Refugees International the GAS had made progress, even developing new capabilities like remote interviewing during the pandemic. But gaps remain.

Greece’s International Protection Act (IPA), effective since January 2020, itself undermines access to protection. The law expands the use of “fast-track” border procedures, which can preclude fair and thorough reviews of asylum claims, resulting in unfounded rejections. It expands the grounds on which applications are deemed inadmissible; extends the maximum duration of asylum seekers’ detention from three to 18 months; and makes it more difficult for rejected applicants to win appeals.

The IPA does provide special procedural guarantees for individuals deemed “vulnerable” because they have certain conditions or marginalized identities.4 But it diminishes these safeguards by no longer prioritizing vulnerable groups’ applications and newly subjecting many to movement restrictions and fast-track procedures.5 Moreover, legal-aid providers told Refugees International they are very concerned about clients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which no longer qualifies as a vulnerability.

An advocate in Lesvos told Refugees International that vulnerability assessments in the registration stage are so quick they sometimes fail to identify survivors of torture and trafficking. People are likely uncomfortable disclosing such traumas in early interactions with authorities. The NGO Fenix reports people seeking asylum on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and/or sex characteristics (SOGIESC) similarly find it difficult “articulating their claim” during registration or asylum interviews because of past stigma, discrimination, or persecution. The process “risks (re)traumatisation and (re)marginalisation of the very people it is meant to protect” if authorities disregard procedural safeguards.

With authorities sometimes issuing first-instance rejections in days, a lawyer at an NGO told Refugees International, “Sometimes we don’t even have time to get to [new applicants] before their cases are decided.” A government official told Refugees International he opposed facilitating lawyers’ access to asylum seekers, claiming they would “coach” applicants to lie to increase their chances of getting protection. He thought applicants should not need help if telling the truth. Such comments suggest an ignorance of the stress and intimidation forcibly displaced people experience, the legal complexity of the asylum standard, and the fundamental role legal aid providers play.

Access to interpretation is also insufficient despite being provided under law. Ultimately, many applicants lack the support they need to navigate the asylum process. An Iraqi asylum seeker told Refugees International he received little assistance from the lawyer assigned to help with his appeal, as the email communication between them was difficult and sporadic. Individuals can also submit “subsequent applications” for asylum if their circumstances have changed but, as of September 2021, have to pay a €100 fee.6 The charge’s prohibitive cost makes it incompatible with EU law.7 And even those who can afford it cannot actually pay because the fee processing system is not yet operational.

In November 2021, the government announced major changes to the registration process for asylum seekers who arrive on mainland Greece or the islands of Crete and Rhodes. Previously, asylum seekers would pre-register with the GAS through Skype then “fully register” in-person at a Regional Asylum Office or Asylum Unit. The new decree eliminates the remote pre-registration step and requires individuals to present themselves at one of two planned reception centers. But the GAS has not specified where the centers will be. Currently, there is only one Reception and Identification Centre (RIC)8 on the mainland—a small RIC in Fylakio, near the Turkish border, that largely processes people apprehended while crossing the border irregularly. Mobile Info Team warns that the RIC lacks capacity to process more asylum claims and that going to Fylakio is often not a “safe or viable option” for people. Thus, most people on the mainland have had no access to asylum—nor, therefore, to protection or assistance—since late November 2021.

Policy in Focus: The “Safe Third Country” Concept

Greece’s Joint Ministerial Decision 42799/2021 (JMD) brings the above trends into sharp focus. Issued in June 2021, it designates Turkey a “safe third country” for asylum seekers from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Somalia, and Syria. This renders their applications “inadmissible”—Greece will not assess the merits of their protection claims because it deems Turkey responsible for doing so.9 That these nationalities accounted for about 68 percent of applicants in 2020 means the majority of asylum seekers in Greece automatically receive first-instance rejections and orders for deportation to Turkey.

In denouncing the JMD, Refugees International and dozens of NGOs argued that Turkey cannot be considered safe for asylum seekers. Most displaced people there cannot access the rights and protections afforded to refugees under international law, and face possible refoulement or chain refoulement.10 Afghan and Syrian asylum seekers told Refugees International neither safely returning to their home countries nor living dignified lives in Turkey was possible.

Concern over returning Afghan asylum seekers intensified in August 2021, after U.S. and NATO troops withdrew from Afghanistan and the Taliban seized power. In the Malakasa refugee camp, approximately 40 kilometers north of Athens, 96 percent of the 1,406 residents were from Afghanistan at the time of Refugees International’s visit. An EUAA representative said all had received negative decisions on grounds of inadmissibility. The Greek Council for Refugees (GCR), which has provided free legal aid to asylum seekers and refugees for more than 30 years, has knowledge of the applications; GCR Advocacy Officer Spyros Oikonomou described what seemed to be “template” decisions, mass-produced without updated or individualized references.

No rulings on appeals had yet been issued. Asked whether developments in Afghanistan would inform the decisions, the EUAA representative said no—only circumstances inside Turkey are considered, leaving little chance of a successful appeal. In one September 2021 case, an appeals committee, reportedly citing a Refugees International report, did rule that an Afghan family with medical vulnerabilities would not be safe in Turkey. The decision underscores the importance of reviewing individual cases rather than applying the JMD automatically.

Meanwhile, Turkey has refused to readmit asylum seekers since March 2020, citing COVID-19 restrictions. According to EU Directives and Greek law, Greece must re-examine asylum claims on their merits if return is impossible.11 But a December 2021 letter confirmed what outside stakeholders told Refugees International they suspected—that Greek authorities had simply stopped sending readmission requests to Turkey because they expected, and wanted to avoid, receiving explicit refusals.

Even before the JMD, the European Commission was concerned about Greek authorities issuing final negative decisions and departure orders to Syrians on the basis of the 2016 EU-Turkey deal. That infamous agreement renders Syrians’ asylum claims inadmissible and orders their return to Turkey. With readmissions suspended, Syrians were stranded in Greece; but they had lost access to aid once their applications were rejected. European Home Affairs Commissioner Ylva Johansson affirmed Greece’s duty to re-examine the claims on substance in light of Turkey’s policy, and continue providing applicants access to material reception conditions, including food and shelter.12

The government has not complied. It announced the JMD soon after, effectively expanding the EU-Turkey deal by applying the safe third country concept to more people. The JMD’s significant impact is seen in rising cases of homelessness, hunger, and administrative detention among people trapped in “legal limbo.” In a December 2021 response to NGOs’ calls for action, Commissioner Johansson reiterated the Greek government’s obligation to conduct in-merit assessments. Coming nearly two years since the suspension, however, her “concerns” and “inquiries” to the Greek government fall short.

In a welcome move, the government announced in November 2021 the JMD would no longer apply to people who had been in Greece for more than one year since leaving Turkey. One person with knowledge of the policy change explained these individuals may no longer have a “meaningful link or connection” that would make it “reasonable and sustainable” to seek asylum in Turkey—normally a condition for applying a safe third country agreement. However, one NGO worker contended that people who only briefly passed through Turkey likewise lack a real connection. Another argued the change was too little too late, as authorities had already rapidly issued rejections to those who might now be exempt.

Material Reception Conditions

Individuals endure difficult conditions in the state-run facilities where most must reside as they undergo asylum procedures. On both the Aegean islands and the mainland, the government is remodeling camps into highly securitized, restrictive facilities.

Island Facilities

Greece has long drawn criticism for the inhumane conditions in RICs on the Aegean islands. Built to accommodate the many arrivals in 2015, RICs were never intended for long-term stays. But as the Greek asylum system faltered and fellow EU States’ support fell short, the camps remained, with growing populations and deteriorating conditions.

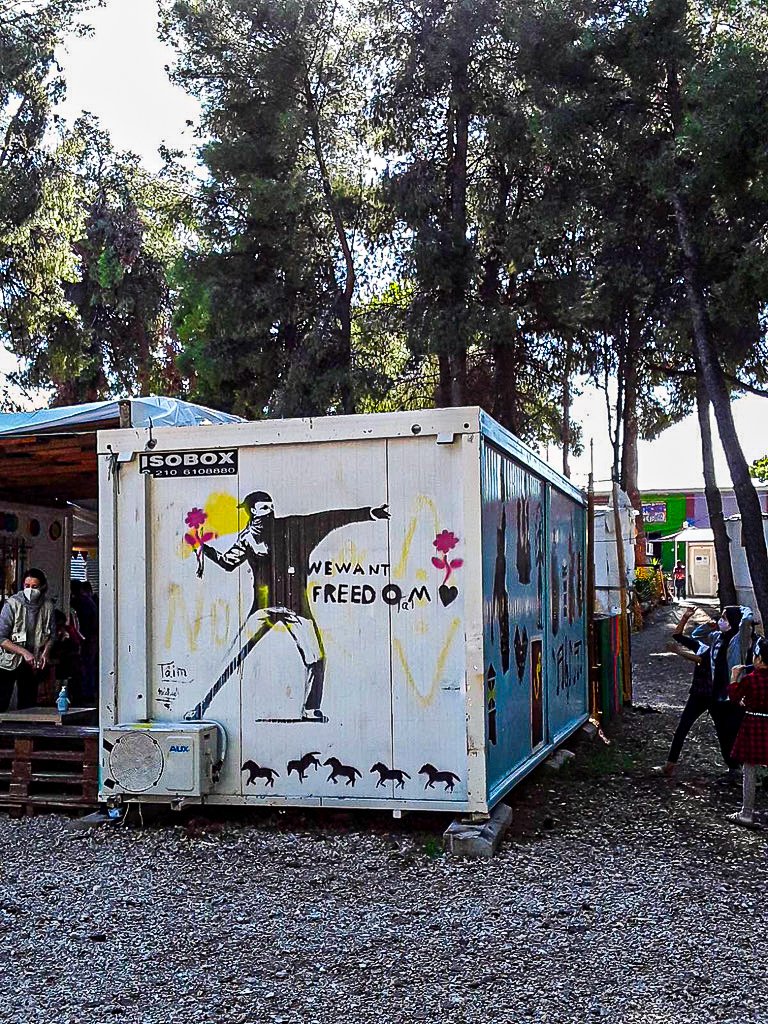

In 2020, Greece announced it would build new facilities, with $276 million in EU grants. Formerly called Multipurpose RICs (MPRICs), the Closed Controlled Access Centres (CCACs) handle all asylum-related procedures from registration to pre-removal detention. After months of protests from local communities and construction delays, the first CCAC opened in Samos in September 2021. CCACs in Kos and Leros opened in late November 2021, and those in Chios and Lesvos should open in 2022. The centers are materially better than what existed before. Residents live in air-conditioned containers with individual bathrooms and kitchen areas. There is—or should be—access to electricity, wi-fi, running water, and wastewater management. Greek and EU leaders promise the “modern” facilities will provide asylum seekers with better, more dignified, and more secure accommodation.But the CCACs are highly securitized structures with restricted entry and exit, built in remote areas. Advocates warned the resulting containment and isolation would undermine residents’ access to aid and services, mental health, and integration. The Council of Europe Human Rights Commissioner warned of large-scale, potentially long-term deprivation of liberty and the then-UNHCR Country Representative urged asylum seekers not be treated as criminals. Detaining someone only because they seek asylum breaches international, EU, and Greek law.13 Though EU officials insisted the facilities would not be closed, official Greek statements indicated otherwise and became reality.

Samos

While the former RIC on Samos was located directly in the main town of Vathy, the new CCAC is about seven kilometers away, in a remote hill area called Zervou. Even just one weekly bus trip to town would consume nearly 20 percent of the average monthly cash allowance people normally receive. Previously, the proximity to town allowed asylum seekers to access essential services provided by NGOs and UN agencies based there, patronize local businesses, and more easily find work and get to school. The CCAC’s location thus inhibits dignified life and beneficial integration into the host community.

At its peak, the RIC hosted about 9,000 people, compared to Samos’ population of 10,000. The deplorable tent camp was a source of shame, even as the presence of the international response fueled misinformation that refugees received outsized assistance. As Greece’s economy struggled, politicians seized on domestic grievances to promote nationalist, anti-refugee positions, while blaming the EU for not doing enough to help. “The central government felt left behind by Europe, and the islands felt left behind by the center,” one local told Refugees International, describing cascading resentment.

Despite having experienced racism and discrimination in town, asylum seekers told Refugees International that being isolated far away was a major loss. Their marginalization is exacerbated by the camp’s restrictions and security. Residents can only come and go between 8:00 am and 8:00 pm. Three-meter-high walls topped with barbed wire form most of the perimeter; in the detention area, they reach four meters. Magnetic gates, X-ray machines, and metal detectors control access to the main entrance and certain areas within the camp, including the safe zone for unaccompanied minors (UAM) and medical unit. All residents and staff must present a valid, government-issued ID card and fingerprint to pass. Cameras throughout the facility allow constant surveillance. Security is managed by a joint force of 300 local police and private security officers. A camp official suggested using private security was “more humane,” but the firm, G4S Global, has been mired in scandals over rights violations before.

A camp official said asylum seekers were “very happy and excited” about the new camp. Some residents acknowledged there were fewer fights and dangers than in the RIC. But in interviews with RI staff and testimony collected by Europe Must Act and the Samos Advocacy Collective, residents consistently described feeling like criminals. Even the sight of row after row of containers surrounded by high walls and barbed-wire fencing—its “fortress-like remove and strict policing”—leaves observers likening the CCAC to a prison.

This impression became a reality for many residents after a Ministerial Order preventing residents without valid IDs from leaving the CCAC. The policy affects rejected applicants, whose asylum cards are revoked, and newcomers yet to receive a card. In December 2021, Amnesty International estimated that about 100 of the approximately 450 residents had been illegally detained this way since the decision took effect in mid-November 2021. Inquiries sent to Greek and EU officials note the government did not issue a public decision providing a legal basis for the policy.

The CCAC is divided into six areas: administration; single-parent families (usually female-headed); UAM; “general population;” shared activities; and “controlled accommodation,” namely pre-return detention for rejected applicants. Overall, it has a 3,000-person capacity, including the 1,000-person detention zone. The general population—primarily single men and families without “vulnerabilities”—is further organized by nationality. During the RI visit, much was still under construction, and everyone resided in the “general population” area. The detention zone, cafeteria, laundry room, and other facilities were not yet operational. The site contract stipulates that 25 percent of the space must be green, but few plants were visible. There are three basketball courts, also with volleyball nets, but there were no balls for play. The only sports area in use during the visit was the soccer field—smaller than a standard field—where NGO staff played spikeball with some young asylum seekers.

Adults and families live in containers that house six to eight people. Refugees International spoke to a young Iraqi asylum seeker who arrived in Greece through Turkey in 2018 and moved into the CCAC upon its opening. Prior, he had spent a year in “the jungle,” the unofficial stretch of makeshift shelters surrounding Vathy camp, then two years in the RIC. In the CCAC, he said, conditions are nicer, but vary. Because the camp is not full, he shares his container with just three other men. But its air conditioning is broken, water leaks from the shower, and the refrigerator is very small. Other containers, he said, have working appliances and bigger refrigerators.

Regardless, residents cannot cook on their own. In a blatant generalization, a camp official justified this by saying it would be a fire hazard because the asylum seekers come from countries without electricity and do not know how to use appliances. Residents told NGOs they were not allowed to bring kitchen supplies into the camp for security reasons, but were also not provided with any. When the cafeteria opens, residents will swipe their ID cards to get food. For now, they rely on twice-daily distributions of prepared food. One asylum seeker said the food was better than in the old camp, but that he sometimes still waited on long lines.

All new arrivals undergo a health assessment, COVID-19 testing, and 14 days of quarantine. The Red Cross provides first aid, and one doctor is on site, but more serious conditions are referred to the public hospital. Just one psychologist works in the CCAC and refers patients who need a psychiatrist to a doctor in town. She said she typically saw ten patients per day in the RIC. Asked about plans to increase healthcare capacity, a camp official acknowledged it was a major gap proving difficult to fill. Authorities tried to incentivize local doctors to work in the CCAC by offering double pay but were unsuccessful. The strong anti-refugee sentiment in Samos partly explains this resistance. But humanitarian workers said some doctors were simply reluctant to work in an under-resourced facility for fear they could be held liable for inadvertent harm.

Asylum seekers also spoke of the urgent need for better healthcare. One man said he waited six months to see a dentist and five months to see the doctor, who could not provide the medication he needed. Instead of seeing the psychologist in-camp, he continues going to Vathy for mental healthcare at the International Rescue Committee (IRC) counseling center. Another said the quality of healthcare in the CCAC was “indescribably” bad. He revealed a small cut that became infected because he did not receive timely and proper care. Wait times could be four to seven hours and being sent alone to the hospital was difficult. Although he had previously received “excellent” care from an NGO working outside the camp, that organization was no longer operating. Reports of racist treatment from medical providers in-camp are particularly concerning.

NGOs are grappling with how to help people in the CCAC. Some NGOs have not been granted permission to work inside the camp. Others have chosen not to, to avoid legitimizing a model they oppose. Samos Volunteers, for example, continues to operate its Alpha Centre in Vathy and established another smaller space, called “Alpha Land,” a short walk away from the CCAC. Immediately next to it is a medical site run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). Given the need for health interventions, mobile MSF teams enter the CCAC to deliver care and information to residents. But, as elsewhere, MSF primarily works outside the camp because it believes asylum seekers should be able to independently access care in safe spaces and not be confined in camps. Similarly, IRC staff prefer to meet clients in their Counseling Center in Vathy.

Lesvos

The CCAC in Lesvos will likely be last to open, delayed by local opposition and bureaucratic red tape. For now, asylum seekers remain in Mavrovouni, a sea-side camp quickly erected after massive fires burned down the infamous Moria RIC in September 2020. The European Commission concurrently established a dedicated taskforce to implement a pilot initiative jointly with Greek authorities to build new, improved reception facilities on Lesvos. Nevertheless, the camp quickly became known as “Moria 2.0” for its similarly abysmal conditions, well documented by NGOs, UNHCR, and media.

Children’s wellbeing is of particular concern. After more than a year of running non-formal education (NFE) activities in makeshift settings, UNICEF received permission in fall 2021 to build a dedicated educational space in Mavrovouni. But a UNICEF representative emphasized that NFE is not an adequate substitute for integrating children into formal education in local schools. Sedigue, an Afghan mother who spoke to Refugees International, said her now-ten-year-old son bused to school daily before the pandemic but had since “lost two years of his childhood.” Without structured lessons or activities, children simply played, risking getting hurt around the trash and construction materials strewn throughout the camp. Moreover, there is no safe zone for UAM.

Sedigue worried most about depression, particularly among the men and young people in the camp. Although not technically in a CCAC, camp residents in Lesvos have faced restrictions on their freedom of movement since the pandemic began. Weekdays, they can only leave the camp for up to three hours from 7:00 am-7:00 pm, and only once every day and a half. On Saturdays, gates close at 5:00 pm. They cannot leave on Sundays.

With nowhere to go, Sedigue said her husband would rise every morning to stand in lines for water and food, then have nothing to do for the rest of each day. Young, single men in particular are languishing, feeling trapped and too depressed to engage in the few activities offered. Sedigue said she had seen men turn to drinking and substance abuse, and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reports high rates of self-harm and suicidal acts. An advocate warned that because they are not a “vulnerable group,” these men often “fall to the bottom of the list,” missing out on critical support and preventive care. Acknowledging the material hardships of camp life, Sedigue said, “All this we can endure; the real risk is to young people’s mental health.”

This, together with testimonies from Samos, validates concerns over the eventual opening of the CCAC in Lesvos. The future camp site is much farther from the main town of Mytilene—more than 30 kilometers—than Zervou is from Vathy. Isolating asylum seekers in such a remote location will present a still greater obstacle to integration and access to services. Even a camp worker in Mavrovouni recognized this. Placing the camp “in the middle of nowhere, out in the wild,” as he said, will create a host of other problems, including transportation to the hospital and schools, telecommunications infrastructure, and facilitating transfers to the mainland. He and other camp workers asserted that, although gaps still exist, conditions in Mavrovouni had improved and things were largely calm. One official, remarking on the extensive construction and planned upgrades, mused that the camp looked less and less temporary.

In fact, conditions in Mavrovouni are not acceptable. But asked why residents should move to a CCAC if it was expected to create problems, some officials said, very frankly, that they did not know. And though they could anticipate certain risks, they had no concrete plans to prevent or mitigate them.

Mainland Facilities

Until recently, asylum seekers on the mainland typically resided in open camps, where they would be referred if unable to support themselves financially. Conditions were generally better in these accommodation sites than in island RICs. The risk COVID-19 presented thus compelled the government to move hundreds of asylum seekers from the overcrowded islands to the mainland. Although some people with vulnerabilities received temporary accommodation in hotels and apartments, most people found themselves in camps. At the same time, land arrivals began increasing—and even surpassed sea arrivals for the first time in 2021—as asylum seekers sought to avoid pushbacks at sea.

But authorities did not adequately adapt to meet the greater need. Mainland facilities soon became overcrowded and conditions deteriorated. Meanwhile, the government began converting these sites into “closed structures”14 that, like the CCACs, enclose residents in securitized, restricted settings.

Eleonas, Malakasa, and Ritsona

Refugees International visited three mainland accommodation sites. Their differences reflected what Spyros Oikonomou of GCR told Refugees International—that authorities’ rather loose and arbitrary interpretation and implementation of the law, as well as weak accountability, mean rules and conditions vary between camps. Nevertheless, they share several challenges.

Eleonas, situated in the center of Athens, most starkly illustrates the decline resulting from population shifts in the last two years. Humanitarian workers told Refugees International that the camp was previously considered relatively decent. But since the pandemic, residents faced “major deprivation,” struggling to access even their most basic needs. At the time of Refugees International’s visit, the camp was at about 110 percent of its 2,000-person capacity. Although many residents have been moved into containers, which house six to eight people, others remain in makeshift tents. Many containers in poor condition are not repaired or replaced. One, visibly burned in an accidental fire, loomed where it had been left, unusable, as children played near the debris.

Malakasa, which encompasses two camps, was operating at 79 percent capacity. Authorities built the second camp during the pandemic to accommodate more people and address overcrowding. In the last year, more residents moved out of small tents and into containers, most with electricity and private kitchens and bathrooms. Just over 100 people remain in large tents known as rubhalls, where they use sheets or other materials to partition off individual living spaces.

About 35 kilometers from Malakasa, Ritsona camp was at 74 percent of its 2,948-person capacity. The population is more diverse than in Malakasa, with most people coming from Syria, Afghanistan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. They reside in containers and pre-fabricated housing units, with access to private kitchens and bathrooms, air conditioning, and hot water. The camp manager said significant improvements had been made to prevent flooding; install infrastructure for access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH); and provide stable electricity and lighting.

Structural improvements have helped mitigate the risk of gender-based violence (GBV), a problem in all camps. In Malakasa, social workers with the UN Migration Agency (IOM), which until 2022 ran Site Management Support (SMS) in mainland facilities, said a lack of electricity and proper shelter and frequent use of communal spaces had made women vulnerable. The move to containers and improved lighting around the camp, as well as awareness raising and safe spaces for women, improved the situation. Women who report incidents can relocate to dedicated safe shelters outside the camp, receive psychological support, and access legal aid. Still, underreporting remains likely because, as one humanitarian worker said, the reality that “justice is the exception, not the rule” in Greece’s weak system disincentivizes filing police reports.

Accessing healthcare is challenging. The national health authority (EODY) staffs medical units, and NGOs also provide services. But they are largely limited to first aid and basic care. Asylum seekers have the right to care at public hospitals but face practical barriers, including transportation, language, and discrimination. Many in Malakasa cannot afford the one-hour train ride to the nearest public hospital, in Athens. The closest public hospital to Ritsona is 18 kilometers away in Chalkida; IOM recently provided funding for daily buses to facilitate access. Whenever possible, interpreters accompany residents.

Healthcare workers said the biggest problems include chronic disease, mental health, and gynecological care. The outbreak of COVID-19 triggered an urgent response, including strict and disproportionate lockdowns. Testing and quarantine protocols remain in effect, and authorities are administering vaccines, using information campaigns to overcome hesitancy. In early November 2021, around 600 residents were vaccinated in Malakasa, which had recorded only 150 infections and one death. About 500 people were vaccinated in Ritsona.

Children living in camps face severe mental health problems and obstacles to education. Staff of Project Elea, a volunteer-based organization working in Eleonas, noted aggressive behavior and attachment issues had escalated during the pandemic. School shutdowns exacerbated conditions. In Malakasa, children could only access NFE, largely organized by residents themselves with support from the NGO Solidarity Now. The Ministry of Education provided some online learning materials, but minimal access to devices and internet limited their reach.

With COVID-19 lockdowns easing, children across camps were able to enroll in public schools at the start of the current school year. But children in Ritsona only began attending school in October 2021 because they lacked transportation, which the regional government is responsible for providing. The Ministry of Education, whose commitment to refugee children several NGO and UN actors applauded, intervened to secure the necessary funding. Nevertheless, obstacles to learning—including language barriers, lack of specially trained teachers, access to school supplies, and bullying—remain. Many children continue relying on NFE.

Youth spaces, language learning, and job information is available in some camps. But, since a change in the IPA, asylum seekers can only legally work six months after registering. Moreover, the difficulty of finding a job and remoteness of some camps mean relatively few residents work. Those who do largely find informal work, where they face exploitation.

The Security Pretext

Except under lockdowns during the pandemic, residents of mainland camps could generally come and go freely, while 24-hour security monitored movement in and out of the camps and activities inside. Now, entry and exit are only allowed from 8:00 am to 8:00 pm. Concrete walls are replacing the fences that surrounded the camps. As in the CCACs, electronic turnstiles line the entrance, where all residents and workers must scan identification cards and fingerprints. Authorities are also installing surveillance and alarm systems, drones, X-ray devices, and metal detectors.

“To fix a container window could take forever; but to build the walls took two weeks,” noted a humanitarian worker in Ritsona. Its electronic security system will soon be installed. Already, however, the walls—and, above all, the restrictions they represent—are affecting residents’ morale. “They ask, ‘Do you think we’re criminals?’” the NGO worker told Refugees International. This starkly contradicts camp authorities’ insistence that the facilities are simply “controlled” and not closed like detention centers.

A government worker in Malakasa said residents wanted the walls in place because they understood it was for their own safety. When the new security system became operational in December 2021, Minister Mitarachi reiterated that the new structures are “to ensure the dignity and safety of beneficiaries, employees, and the local community.” But NGO workers, UN representatives, and displaced people Refugees International spoke with do not believe the added security and physical barriers will address safety problems inside camps. They acknowledged that violence and petty crime, including drug use and theft, occur and that people without valid cause for being in the camp could enter unsecured points. But the primary threats to residents’ safety come from GBV, harassment of marginalized groups like LGBTQ+ individuals, and fights over things like food among residents. Building walls will not address these issues. Indeed, Minister Mitarachi’s emphasis on the government’s aim to “drastically reduce the effects of the crisis on the local communities” reveals what many believe to be the true priority behind the new measures—not ensuring displaced individuals’ safety, but exerting control, demonstrating a hard stance, and appeasing locals opposed to the camps.

Eleonas remains an unrestricted site. Although Greek police and private security officers are present, the entrance was open on both RI visits. One humanitarian worker said it did not cause major issues. But rather than fortify Eleonas like the other camps or implement alternative measures that could improve security, the city will dismantle it. After repeated threats to do so, the Athens’ Municipal Council voted in December 2021 to end the contract for the lot Eleonas sits on. While next steps are unclear, current residents will likely have to move to one of the other, more restrictive facilities on the mainland, farther from the city.

Doubling down on costly measures to isolate and surveil asylum seekers is a mistake. An NGO representative emphasized that guaranteeing camp security should mean making people feel safe inside—not securitizing the camps. In an already hostile environment, the new measures, together with Greek leaders’ public statements, risk promoting a harmful misperception that asylum seekers are themselves threats to local communities, rather than those needing security.

Policy in Focus: Aid Cutbacks and Cutoffs

The government has also sought to exert control by narrowly regulating the aid asylum seekers receive. In April 2021, the MoMA announced cuts to financial assistance for asylum seekers not living in State-managed accommodation as of July 1, 2021. The change affected an estimated 25,000 people, primarily in urban areas. The many unable to afford their rent without financial aid had to give up the freedom of independent housing and move into camps. GCR told Refugees International that in several cases, the MoMA assigned people to places in different towns or cities without arranging transportation, which they could not afford on their own. NGOs, including Refugees International, warned the policy seriously undermines asylum seekers’ autonomy and integration and questioned its legal basis.

Rather than move into camps, asylum seekers with vulnerabilities could try to secure a rented apartment under the EU-funded Emergency Support to Integration & Accommodation (ESTIA) scheme. But since the government took over management of the accommodation program from UNHCR in July 2020 and cut its budget by 30 percent, the program has been plagued with issues affecting the housing quality.

The problematic transfer of ESTIA’s accommodation scheme forebode problems with the transfer of its cash assistance component. Despite having plenty of time to prepare, when the MoMA took over the program in October 2021, it was unable to implement it. The Ministry insisted the resulting suspension of cash distribution would be brief, but only issued a tender for an implementing partner in November 2021. Asked to explain the gap, a government official said months of negotiations with its intended partner had fallen through at the last minute.

Refugees International, with dozens of NGOs, repeatedly called on the government to address the issue and its fallout and urged the EU to intervene. Cash aid is one of the most effective forms of humanitarian intervention. In Greece, asylum seekers living both inside and outside camps rely on cash to purchase basic necessities and essential services. While accompanying the Lighthouse Relief Streetworks Outreach program in Athens, Refugees International met individuals eager for cash vouchers to cover food and medical expenses—they were dejected to learn none were available. Cash aid has been especially critical as pandemic lockdowns made finding work more difficult, leaving people with no other income.

The cash freeze raised concerns about people going hungry. On the islands, camp residents use cash to supplement the food provided, which can be inadequate or unappealing. On the mainland, asylum seekers previously received slightly higher cash allowances to purchase and prepare their own food. When payments stopped, the government began catering food to those inside camps. But an NGO worker described the food distribution in Ritsona as a “chaotic, dehumanizing, free-for-all.” A private catering company distributed prepared meals at a set time, six days a week, for eligible residents. But the process was largely unregulated—there were no lines, fights sometimes broke out, and disappointment with the food quality and quantity triggered protests. Much food remained unclaimed after each distribution.

Even this dismal option was unavailable to many people on the mainland. Outside the camps, asylum seekers living independently or in ESTIA apartments did not receive food distributions and had to seek out help from charities. And inside the camp, an estimated 40 percent of residents were ineligible for food. They include newly arrived individuals yet to acquire their documents due to bureaucratic delays; those whose claims were rejected on merit or inadmissibility but could not be deported; and individuals who received positive decisions but remained in camps because, without integration support, they risked homelessness and destitution.[15] Under the IPA, none have access to material reception conditions, including food.[16] As one NGO representative put it, “Whether approved or rejected, the outcome is the same—they are out of the government’s hands.”

But using policy to render people “out” of the asylum system does not absolve the government of all its responsibilities. As Commissioner Johansson emphasized in her aforementioned December 2021 letter, under EU law, all persons, irrespective of status, must receive basic means of subsistence.[17] Some camp workers Refugees International spoke with said officials were still not strictly enforcing the policies. But people cannot rely on camp managers’ whims for their survival.

About four months after the last cash distribution, the MoMA finally contracted an implementing partner—Catholic Relief Services, the same NGO that had implemented the program under UNHCR. Authorities began distributing cash cards and back payments on December 31, 2021, and the normal disbursement schedule will resume on March 1, 2022. But the system can only account for currently registered asylum seekers—anyone who received their asylum decision between October and December and is no longer eligible for a cash card cannot receive back payments owed them. Moreover, the government is considering continuing to provide mainland camp residents with catered food and the lower cash amount, though many prefer to prepare their own food. Finally, the contract only runs until August 31, 2022—if the government again fails to prepare, there could be another lapse in just months.

The Supposed Inevitability of Camps

Greek and EU leaders justifying the new camps argue that since States must manage displaced populations somehow, they should at least make facilities decent and convenient, with all services in one place. They revert to the same refrain: that conditions in the CCAC are materially better than in the former RIC. Advocates do not deny this. But it is a simplistic and unsatisfying defense. First, the deplorable conditions in the RIC are no standard for comparison. Second, morally, if not legally, Greece owes asylum seekers more than their most basic material needs. Allowing people small freedoms like preparing their own food can have an outsized impact on their wellbeing. At the same time, to flaunt playgrounds and wi-fi while residents struggle with their health, underscores authorities’ insensitivity to some major issues.

Moreover, the deterioration of conditions in other camps, notably in Eleonas, inevitably raise questions about how long this defense can last. Simple neglect or the inability to adapt in case of more arrivals could mean the new containers are soon in disrepair. Rather than waste funds on supposedly temporary measures, the government should invest in a sustainable and resilient reception system. But politics shapes every decision—a UN worker noted authorities could have installed pre-fabricated units, which are sturdier than containers, in all the camps. But they likely chose containers because “they look more temporary,” and thus send an important message to voters.

Some humanitarian workers said they could accept the CCACs if authorities truly used them just as initial reception centers for very short stays and guaranteed full protection of residents’ rights, including access to quality services and freedom of movement. Others warn against acquiescing in the narrative that having large camps is inevitable. “Authorities have put forward this notion that we need big camps, that they’re nonnegotiable,” says one lawyer. “So we applaud the new conditions with caveats, but then everyone forgets about the caveats. We need to challenge the whole framework.” An alternative model involving initial processing at borders and decentralized accommodation is feasible, he says, and does not require building large-scale facilities.

Completely overturning Greece’s approach should be the ultimate aim, but trends are moving in the opposite direction—with the EU’s strong backing, Greece appears to be a testing ground for other EU States. In this context, advocates have focused on using past experience to anticipate problems in the CCACs, monitoring conditions and residents’ wellness, and proposing concrete measures to mitigate and prevent harm.

Creating an Enabling Environment

The Greek government’s claim to be “in control of the situation” belies the numerous obstacles to protection and the inhumane conditions asylum seekers continue facing. Fewer asylum seekers arriving, waiting for decisions, and living in camps does not indicate sound management if it results from denying people their full rights. Reversing policies that undermine protection is critical. The preceding discussion also reveals four essential factors for a better operational response.

Forethought

The government’s policies reinforce a public message that refugee reception is a temporary challenge, mirroring the EU’s crisis-driven approach. If unable to adjust capacity in response to changing demand, the government—and NGOs and IOs working beside it—will be left reeling from one emergency to another. For example, UN representatives acknowledged that higher rates of school enrollment could simply reflect that there are fewer children to enroll. The government must be able to mobilize resources to absorb new arrivals and sustain high rates of enrollment, if necessary. Similarly, the State’s responsibility to displaced people does not end as soon as an asylum decision is made. A narrow focus on material reception conditions and models that inhibit early integration undermine people’s prospects for self-sufficiency later on.

Although migration and displacement are dynamic and often unpredictable, the government has not delivered even when it could anticipate having to increase or adjust its response, or even demanded taking greater responsibility for operations. Authorities’ failure to renew expiring contracts, secure implementing partners, or otherwise prepare for transitions has disrupted critical services, ultimately harming the people the services should protect. One UN worker told Refugees International, “When we hear something is being transferred to the government, we automatically foresee a gap.” There was anxiety about upcoming shifts, for example in the management of Site Management Support and child protection, given the lack of clarity on exactly who would manage the roles and how. Early in 2022, the UN worker said the MoMA’s takeover of on-site cleaning and security contracts had in fact gone well. This only underscores that the government does have the capacity to manage the response if it commits to preparing—an effort it must sustain.

Trust

In interviews, humanitarian workers and advocates often expressed frustration over the government’s repeated, preventable lapses. The pattern led some to question the government’s political will to assist asylum seekers. Others pointed out that, “The government’s political agenda is not a secret.” Indeed, the administration is explicit about its aim to cut off irregular migration, in line with campaign promises. But even when it purports to act in asylum seekers’ interests, counterproductive policy choices suggest that is not the true goal.

Meanwhile, government officials’ concerns that some external stakeholders want to “do things their own way,” likely drove decisions to assume program management from UN agencies and create an NGO “transparency registry.” Organizations say the registry’s application requirements are excessive and that criteria are applied inconsistently. Many applicants have faced long waits, only to be rejected over minor administrative errors or grounds incompatible with law. No NGOs with which Refugees International spoke oppose a registry per se. Rather, they oppose a process that is so burdensome and unfairly applied that it effectively bars organizations from carrying out life-saving work and breaches the right to freedom of association.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders cites various examples of “bureaucratic harassment” and the “delegitimization and criminalization of solidarity [with displaced people].” The government is even prosecuting aid workers involved in search-and-rescue operations. But when asked from whom they had received help since arriving in Greece, all asylum seekers with whom Refugees International spoke named NGOs. Organizations point out the irony that the government regularly requests and relies on them to deliver services even as it undermines them.

NGOs are particularly concerned about their inability to provide services and monitor conditions in the new reception facilities. Previously, camp managers sometimes allowed unregistered NGOs to continue operating because the managers recognized the NGOs’ added value. But they will have less discretion in securitized camps, as staff of unregistered organizations will lack ID cards required to enter.

The result is that an “antagonistic and suspicious attitude” is reflected in policy governing NGOs, undermining prospects for effective engagement and inflaming an already hostile public view. In Samos and Lesvos, Greek and foreign journalists, lawyers, and activists told Refugees International they faced intimidation, harassment, and direct attacks from neighbors and authorities. More broadly, some in Lesvos described a sense that international NGO and UN workers had arrogantly “taken over” since 2015. But in interviews, UN and NGO representatives emphasized that reception and protection are responsibilities of the State, which they do not want to substitute. Rather, they supplement capacity to meet obvious outstanding needs.

Coordination

Underlying tensions hinder coordination between stakeholders. Interviews revealed misunderstandings and missing information, as well as missed opportunities around shared interests. Several people cited a lack of transparency and availability of valid data as a major problem. Better coordination could improve information collection and exchange needed to identify challenges, design appropriate solutions, and reliably deliver services.

Stakeholders had varying impressions of formal coordination mechanisms that do exist, such as UN-led Working Groups. Some considered fora in which government representatives actively participated to be most effective, as having government input from the early stage of decision-making helped ensure decisions could actually be resourced and implemented.

But a lack of internal coordination among the many government ministries involved also creates problems. Lapses affected some asylum seekers’ access to healthcare, employment, and other essential services under a new social security scheme, while parallel data collection efforts within the MoMA and Ministry of Education obscure and duplicate information about displaced children’s education outcomes.

For camp managers, the CCACs’ staggered openings create an opportunity to apply lessons from one camp to the others—and thus prevent additional suffering—as the model becomes operational. A camp official in Mavrovouni told Refugees International it would be telling to see how the Samos CCAC copes if arrivals increase dramatically. But when asked, he said there is no mechanism to exchange such lessons with his counterparts. He said one would be useful.

The complex history of the guardianship program illustrates several gaps within and between stakeholders. Built and managed by the NGO METAdrasi, the program was later transferred to the Ministry of Labor & Social Affairs then the MoMA. Despite METAdrasi’s efforts, government officials never made any meaningful attempt to facilitate knowledge transfer from the NGO. Years later, there is no implementing partner contracted and the MoMA, “despite knowing that it would take over the Guardianship, does not seem to be prepared to guarantee at least a transitional period.” Child advocates are unsure what the future will look like, warning that hundreds of children could be left without representation. Separately, one NGO worker expressed reservations about IOM taking over responsibility for child protection case management from NGOs in 2022. Ultimately, the situation demonstrates how poor coordination leaves potential unmet, wastes resources, and hinders effective reception and integration of asylum seekers.

Regional Solidarity

The absence of a regional approach to asylum has allowed EU States to avoid responsibility sharing. In September 2020, the European Commission proposed a new Pact on Migration and Asylum, promising to establish a coherent, comprehensive approach. But its plan, which remains stalled in negotiations, is unlikely to effectively address the challenges faced by frontline States like Greece. A mandatory “solidarity mechanism” that prioritizes relocation is key. Although ad hoc relocation schemes have helped share responsibility among willing EU Member States in the past, only a permanent, predictable mechanism may prevent crisis-like reactions and strain on Greece’s asylum and social systems.

Indeed, although insufficient support from other EU States does not excuse the mistreatment of asylum seekers, Greece should not have to manage what is a regional matter on its own. Sharing responsibility will enable Greece to better provide humane reception conditions and ongoing support to asylum seekers and refugees.

Financial support also remains critical to ensuring Greece provides an adequate response. All stakeholders expressed concern about the future of reception in the context of an increasingly “limited fiscal space.” Under the next EU budget period, 2020-2027, Greece will receive €1 billion for migrant and refugee support programs—a significant cut from €3.4 billion in the previous seven-year term. The EU based its decision on the reduction in asylum seekers arriving in Greece, which risks endorsing the externalization and dangerous practices that, as noted above, partly explain this trend. Given the government’s stated goals and actions to date, one humanitarian worker warned that depending on the allocation of national funds is “precarious.” Already, decisions about where to make cuts—such as removing safe spaces for women from some camps—raise significant concern.

Conclusion

Restrictive new policies and camps perpetuate a Greek strategy of deterrence, containment, and exclusion that systematically closes the space for asylum. The government—together with EU, UN, and NGO partners, and displaced people themselves—must halt or reverse implementation of policies that cause these harms. Responsibly and humanely managing asylum and reception requires taking the long view and implementing an approach that puts displaced people first.

Endnotes

1. Pushbacks undermine protection from refoulement. Non-refoulement is a fundamental principle of international law that prohibits States from forcibly returning refugees or asylum seekers to a country where their lives would be in danger.

2. See, for example, reports and remarks from civil society, the Greek Ombudsman, UN agencies, the Council of Europe, and the European Commission and Parliament.

3. The EUAA, formerly the European Asylum Support Office (EASO), is an EU agency that serves as a resource to Member States to support their application of the EU laws that govern asylum, international protection, and reception conditions (the Common European Asylum System, CEAS). It does not replace national asylum or reception authorities but provides various forms of practical, legal, technical, advisory, and operational assistance.

4. Per Hellenic Republic Law No. 4636/2019 (1 November 2019) Articles 39(5) and 581, “vulnerable groups” comprise children, both unaccompanied and in families; direct relatives of victims of shipwrecks; persons with disabilities; older persons; pregnant women; single parents with minor children; victims of human trafficking; persons with serious illnesses; persons with cognitive or mental disabilities; and survivors of torture, rape, or other severe forms of psychological, physical, or sexual violence.

5. Asylum seekers who arrive on the Aegean Islands are typically subjected to a “geographical restriction” that requires them to remain there. The IPA revoked the prior exemption for most persons with vulnerabilities, except unaccompanied children under 15 and victims of torture or trafficking.

6. A subsequent application is one that is resubmitted following a final rejection decision by the police, GAS, or Board of Appeal, when an applicant has new reasons for which they are requesting international protection. The fee was introduced in a controversial bill tabled in August 2021 that amended deportation, return, and asylum procedures. It passed in September 2021 as Law No 4825/2021 (A’ 157/4-9-2021).

7. Article 38(4) of the Asylum Procedures Directive (Directive 2013/32/EU) provides that “Member States shall ensure that access to a procedure is given in accordance with the basic principles and guarantees described in Chapter II.”

8. Also known as “hotspots,” the RICs were set up by the EU to serve as temporary sites of first reception to coordinate operational support from EU agencies to Member States faced with “disproportionate migratory pressure,” helping them swiftly identify, medically screen, register, and fingerprint migrants, and facilitate the implementation of relocation and returns.

9. For other cases in which an EUMS can decide not to examine a claim for international protection, see: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/pages/glossary/inadmissible-application-international-protection_en.

10. Turkey is party to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention but retains the geographic limitation only recognizing as refugees people originating from Europe. Syrians are afforded temporary protection status, which grants some basic rights, while non-Syrians lack even these.

11. This is in line with UNHCR guidelines that governments should only apply the safe third country concept when asylum seekers can be returned to the country and safely await a status determination through a fair procedure there.

12. Under EU law, “reception conditions” are the full set of measures that Member States grant to asylum applicants in accordance with what is known as the Reception Conditions Directive. Material reception conditions “include housing, food and clothing provided in kind, or as financial allowances or in vouchers, or a combination of the three, and a daily expenses allowance.” Source: EUR-Lex. See also: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/policies/migration-and-asylum/common-european-asylum-system/reception-conditions_en.

13. See respectively: The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) Article 31. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU (2009) Articles 6 and 52(1); Reception Conditions Directive (26 June 2013) Recital 15 and Article; Dublin III Regulation (1990) Recital 20 and Article 28; Asylum Procedures Directive (26 June 2013) Article 26. And Hellenic Republic Law No. 4636/2019 (1 November 2019) Article 45-46.

14. Formally “Controlled Centers for Temporary Accommodation of Asylum Seekers,” or KED for its Greek acronym

15. A forthcoming RI report explores this in depth.

16. Article 111, Law 4674/2020 introduced an amendment to Art.114 of L.4636/2019 (International Protection Act, IPA) in March 2020.

17. Namely, the provisions of the Reception Conditions Directive, the Qualifications Directive and the Return Directive, and from the relevant provisions of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

PHOTO BANNER CAPTION: Portrait of a man in the Closed Controlled Access Centre in Zervou, on the island of Samos. Photo Credit: Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto via Getty Images.