Seeking Asylum in Greece: Women and Unaccompanied Children Struggle to Survive

At the height of recent irregular migration to Europe in 2015, Greece was a transit country and gateway into the European Union (EU). Most asylum seekers and migrants moved onward from the Greek Aegean islands to other parts of Europe. With increases in the flow of asylum seekers from Turkey to Greece and the closure of other European borders, however, Greece has transformed from a short stopover for asylum seekers to a host country for large numbers of refugees.

The country has consistently demonstrated that it is ill equipped to handle this role. The Greek government continues to implement a “containment” policy that forces incoming asylum seekers to remain on the islands until they go through their asylum procedures. While there, they lack adequate access to essential services and often even the most rudimentary accommodations.

These conditions create enormous protection risks for asylum seekers, especially for women, girls, and unaccompanied children (UAC).[1] Women and girls are at heightened risk of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), and UAC are at risk of being trafficked and exposed to other forms of exploitation, yet there are not enough trained law enforcement officers at the reception centers to ensure the security of these vulnerable groups.

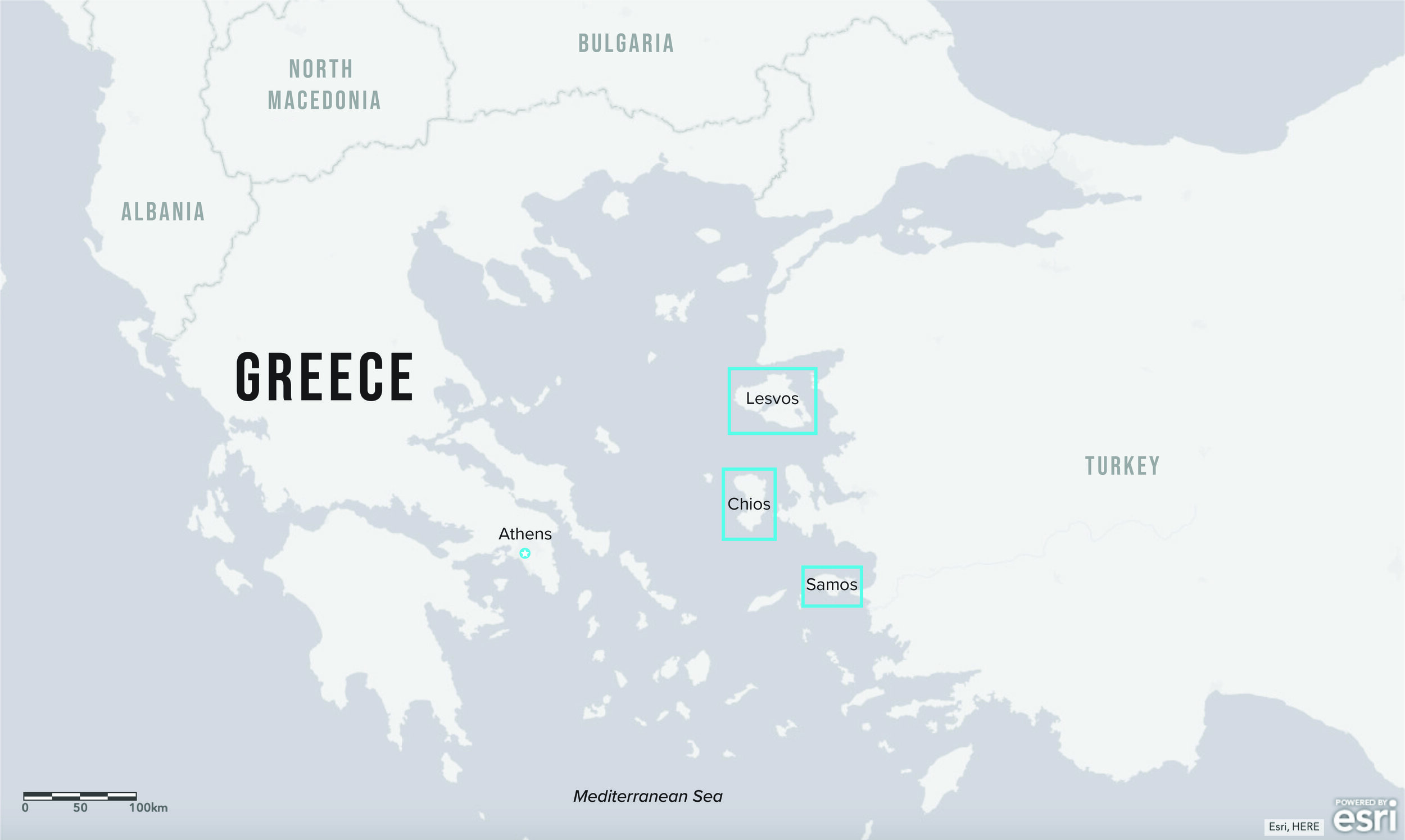

Furthermore, there is a severe shortage of social service providers, such as doctors, psychologists, and social workers, as well as interpreters. The situation for asylum seekers on the islands of Lesvos, Chios, and Samos is particularly stark. Massive overcrowding, deteriorating conditions, and a backlog of asylum cases endanger asylum seekers’ well-being and safety.

The enormous number of UAC in Greece—both on the islands and mainland Greece—who lack adequate protection is especially alarming. Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the Greek government announced a new policy, “No Child Alone,” in November 2019. Although not yet enforced, the policy commits the Greek government to providing safe accommodation and access to social services for UAC. In tandem with its “Guardianship law,” the new policy provides that the government will hire enough staff to act as legal guardians for all UAC.

Although this policy is an important step in the right direction, the Greek government has otherwise largely failed to make a meaningful effort to improve poor conditions for asylum seekers who have stayed on the islands for years. If the government hopes that such conditions will deter new refugees and asylum seekers, it is mistaken.

The factors that drive people to flee their countries in the first place have not diminished—indeed, many of them are growing more acute. The security situation in Afghanistan continues to deteriorate, millions of Syrians are unable to return home, and conflict and persecution persist in parts of Africa and elsewhere. With no resolution of these root causes in sight, and so few legal pathways available for refugees to access the EU, irregular migration to Europe will continue.

Greece needs to be better prepared for these arrivals. Although the EU has already allocated more than €2 billion to help Greece improve its capacity to manage this migration challenge, the funds have not resulted in meaningful improvements in the conditions that greet those seeking refuge. Greece still lacks the capacity to receive asylum seekers, care for them, adjudicate their claims, and then integrate those who qualify. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), which have a valuable role to play in this response, have stepped in to try to fill some of the gaps. Coordination needs to improve, however, and the Greek government should not rely on civil society to do the work for which it is responsible.

The EU must also take greater responsibility for asylum seekers searching for safety in Europe, many of whom arrive in Greece. It is especially important that the EU act in solidarity with Greece to assist the most at-risk groups of asylum seekers. Substantial numbers of UAC in Greece have close family members in other EU countries. However, the family reunification process is cumbersome, resulting in needless family separation and additional strain on Greek social systems.

The challenges Greece faces in receiving large numbers of asylum seekers are real, but most of them can be overcome with increased capacity and political will. The Greek government and the EU have an obligation to receive asylum seekers and hear their claims for international protection. Even the EU’s own directive considers seeking asylum to be a “fundamental right.” While in the asylum process, all applicants should be afforded safety and the ability to meet their basic needs according to humanitarian standards. However, on the Greek islands that currently is not the case. The conditions are so abhorrent that vulnerable groups, such as women, girls, and UAC, often find that the situation for them is even less safe than the conflicts they fled. This situation is unacceptable and undermines the very principle of asylum.

Recommendations

To the Greek authorities:

- End the “containment policy” and allow asylum seekers on the islands to travel to the Greek mainland, where conditions are relatively better. Also, ensure that once they arrive, they will have access to safe living conditions, livelihood opportunities, and adequate psychosocial and medical care.

- Hire more civil servants to work as medical professionals, social workers, psychologists, lawyers, guardians, and interpreters, especially for those islands hosting sizable numbers of asylum seekers.

- Ensure that law enforcement officers are present in asylum seeker accommodation areas and trained on how to deal appropriately with gender-based violence (GBV), protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA), and basic refugee rights.

- Provide sex-segregated accommodation and latrines with locks and lights for asylum seekers, consistent with the globally recognized Sphere standards.

- Implement all aspects of the “No Child Alone” plan as soon as possible, fulfilling its commitments to provide UAC with the protections they are due, including safe accommodations, legal assistance, access to basic services, and adequate supervision under the Guardianship law.

- Prioritize the relocation of UAC to other EU member states and establish criteria for selecting children to participate in the relocation program. Also, cooperate with states to identify UAC appropriate for further asylum processing outside of Greece.

To the EU and its member states:

- Develop more legal channels, such as humanitarian visas, for asylum seekers to enter Europe.

- Consistent with the request of the government of Greece, relocate at least 3,000 UAC, through newly established criteria, to other EU member states to proceed with their asylum process.

- Simplify requirements for family reunification and relax strict deadlines.

To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and NGOs:

- Collaborate with government authorities to hold regular, well-publicized information sessions to educate asylum seekers about their rights, providing examples of gender-based violence, and clearly explaining how they can report incidents of violence, abuse, and exploitation.

- Conduct regular mapping of NGOs and services available.

- Provide SGBV survivors with comprehensive case management until the government has the capacity to do so, including timely access to safe accommodation, medical care, psychosocial support, and legal aid.

Background

Between 2015 and the beginning of 2016, more than 1 million migrants and asylum seekers traveled in boats from Turkey to the Greek Aegean islands. Virtually all of the arrivals quickly transited through Greece and settled in other European countries, most notably Germany.

Greece—and the European Union (EU) more broadly—was entirely unprepared for this spike in migration. They were also ill equipped to address the needs of these arrivals, many of whom had fled severe violence and persecution. Other southern European countries closed their borders, leaving tens of thousands of asylum seekers stranded within Greece. In response, Greece invested more resources into its newly created Greek Asylum Services (GAS) but also pleaded for EU assistance.

In an effort to “end the irregular migration from Turkey to the EU,” the EU negotiated an unprecedented and far-reaching deal with Turkey in March 2016. The EU initially pledged €3 billion to please President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government and made several other political gestures beneficial to Turkey. In exchange, Turkey agreed to “take any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration” from Turkey to the EU. Turkey also agreed to permit Greece to return asylum seekers to Turkey without first reviewing their requests for international protection or after rejecting their asylum claims. In addition, for every Syrian that Greece returned to Turkey, the EU would resettle one Syrian to Europe.[2]

At the time, human rights groups deemed Turkey to be unsafe for many asylum seekers, and the situation for asylum seekers there continues to worsen. As soon as the agreement was implemented, however, it did have the intended effect—the number of arrivals to Greece fell dramatically, to an average of approximately 2,500 people per month. This sharp drop was a direct result of the Turkish government’s efforts to prevent people from leaving for Greece. In the summer of 2019, however, there was a significant uptick in the number of arrivals to Greece from Turkey, which peaked at more than 10,000 during September 2019.

The notable increase was led by a growing number of Afghans seeking asylum in Europe. More than 40 percent of the arrivals in 2019 were Afghan, followed by 25 percent from Syria. Continued insecurity in their home countries, widening hostility toward refugees in Turkey, and threats of deportation from Turkey explain the high numbers. Turkey’s decision to deport Afghans back to Afghanistan was particularly alarming, given that 2018 was the deadliest year in Afghanistan since the most recent conflict began in 2001.

Asylum seekers who arrive on the Greek islands are met by horrific conditions in their reception centers. The Greek government’s “containment” policy, instituted as part of the EU-Turkey deal, requires them to remain on the island where they arrived (3) until their asylum claims are decided. This policy complements the “hotspot” approach taken by the European Commission. Hotspots are specific locations in Greece and Italy where the respective governments concentrate asylum seekers so the authorities can more easily undertake asylum procedures and, if necessary, conduct readmission operations. Originally devised as a way to more easily return rejected asylum seekers to Turkey, the containment policy has instead resulted in massively overcrowded camps. The number of asylum seekers waiting to be processed has completely overwhelmed the capacity of reception facilities and service providers to meet their most basic needs.

Human rights actors—including Refugees International—have for years urged the Greek government to change this policy of containment, but to no avail. Instead, in November 2019, Greece passed a new law that aims to create closed detention centers on the islands. The law also commits to processing asylum claims faster, but without the proper protections and checks in place.[4]

As of the end of November 2019, the total number of asylum applications pending a decision by GAS stood at 83,633. Of this enormous backlog, nearly half are for asylum seekers restricted to the islands. About 20,000 of the asylum seekers waiting on the islands for their cases to be processed are women and children. The already overcrowded, unsanitary, and unsafe reception centers built to host a maximum of 5,400 people now host more than 42,000—they are over capacity by almost 800 percent. This severe overcrowding has led to deplorable conditions for asylum seekers, who find themselves living in makeshift camps outside of the official Reception and Identification Centers (RICs). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recently described conditions in Moria, the largest RIC,(5) as “extremely disturbing.”

Research Overview

Refugees International previously traveled to Greece in 2016 and 2017 to assess the mass migration into Europe and effects of the EU-Turkey deal, as highlighted in the report ‘Like A Prison’: Asylum-Seekers Confined to the Greek Islands.

In November and December 2019, a team of Refugees International staff returned to Greece to take account of the humanitarian and political responses to the recent surge of asylum seekers who arrived during the summer of 2019. The team traveled to Athens, Lesvos, Chios, and Samos. They interviewed asylum seekers of all ages and a number of nationalities. The team also interviewed staff of local and international NGOs, UN agencies, Frontex (the European Border and Coast Guard), and residents of the host communities. In addition, the team met with organizations in Athens working on migration issues in Greece.

Women and Girls

More than 60 percent of asylum seekers in Greece are women and children. In addition to—and, in some cases, as a result of—the dismal living conditions on the islands, women and children there face significant protection risks and are unable to access basic services. For women and girls specifically, safety and security are the most pressing concerns.

Security

Refugees International met with women asylum seekers on the three islands of Lesvos, Chios, and Samos. All of the women highlighted security as their greatest problem. An NGO staffer who has worked on all three islands said, “These camps are not safe. The Greek government is responsible for the safety of asylum seekers if they are forcing these people to stay on the islands. And the government is utterly failing. These camps are lawless, chaotic places, and women and girls are the first to suffer.”

Women and girls fear walking alone because police presence is minimal or non-existent, and tensions in the “hotspots” (6)—designated areas where RICs are located—are high. “You can basically say that there are no police. The police that are around are to protect the government staff, not the refugees,” a lawyer in Lesvos told the Refugees International team. Further, a social worker in Lesvos remarked, “there is probably one stabbing per day in Moria—most of them we just don’t hear about because this kind of thing has become so commonplace.” As recently as January 17, 2019, an asylum seeker stabbed and killed another in Moria—not the first death of this kind.

In addition to direct attacks, women and girls also fear that if they move within the hotspots, they will be caught in the kinds of violent fights that regularly break out between various groups of asylum seekers. The Greek authorities thus urgently need to increase police presence in the hotspots. Because there are not enough local police officers, the national government should deploy police from other parts of the country to the islands. To prevent police from abusing their power and prepare them to handle the unique circumstances on the islands, authorities must train all officers on basic refugee rights, gender-based violence (GBV), and prevention of sexual exploitation and abuse (PSEA). The officers should have a clear mandate to improve security in the hotspots by protecting everyone—staff and asylum seekers alike.

Absence of Sufficient and Safe Latrines

Within the RICs, asylum seekers are crowded either into intermodal containers—better known as ISO boxes—or in tents between the ISO boxes. Outside of the RICs, most people live in flimsy camping tents or in the open air. For all of the people restricted to islands, the only toilets for their use are the few latrines located in public areas inside and outside of the RICs. The overflow areas adjacent to the official RICs have grown so large and have so few latrines that many people must walk long distances and wait in enormous lines to use the toilets. Indeed, in some places, there is only one latrine for every 200 to 300 people. Moreover, during every interview the Refugees International team conducted, women and girls commented that they are afraid to use the few latrines available in the hotspots because they risk being attacked. Several women explained that they urinate in bottles inside their tents or trailers, or resort to wearing diapers to avoid traveling to the toilets. Risks are especially high at night because most of the latrines do not have lights.

Aziza, a young Afghan woman living with her uncle, husband, and small baby in the “Olive Grove” of Moria said, “I can’t use the toilet. Men and boys are everywhere and there are no rules here. I just try not to drink anything so that I don’t need to go outside of my tent.” Aziza has been restricting herself from drinking much water for five months already, and her asylum interview—of which the outcome is not certain—is not scheduled until May 2020. Meanwhile, according to NGO representatives, security is only getting worse.

This situation is both unacceptable and indicative of the overall lack of basic security in the hotspots. The Greek government must immediately upgrade each of the RICs to provide adequate sex-segregated accommodations and enough latrines to serve the growing population within and outside of the official boundaries of the RICs. These latrines need to have lights and locks to mitigate the risks that women and girls currently face. These are the most basic pieces of infrastructure required in any humanitarian emergency and should have been prioritized years ago.

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

As overall security continues to deteriorate in the ever-expanding hotspots, it is unsurprising that sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) persists.(7) NGO personnel told Refugees International that SGBV within the camps—including intimate partner violence, rape, sexual harassment, transactional sex, and physical assault—is rampant.[8] Although violence perpetrated by unknown people is common, an organization in Lesvos specializing in SGBV prevention and response noted that intimate partner violence is probably the most widespread form of SGBV occurring regularly in all of the camps. There is little that can be done when a woman reports domestic abuse, however. NGOs are rarely in a position to intervene, and most legal aid providers on the islands focus on asylum law—neither their mandates nor their expertise include prosecuting domestic violence cases.

Women and girls also arrive to Greece having already experienced SGBV in their countries of origin or en route to Europe. Refugees International spoke to 25-year-old Mercy,[9] who is from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and lives in an ISO box in the Moria RIC with a dozen other single women.[10] “Greece is a long way from Congo,” she said. “I fled because I was raped there and the fighting never ends. But I traveled alone, which was also unsafe. This was my second time trying to get to Europe. The first time the Turkish police caught me. I was out of money so I had to do whatever the smuggler said. Thanks to God that I made it, but it’s so much worse here than I ever could have imagined, and the harassment is unbearable.”

Provision of Information

UNHCR’s role in Greece is to provide information to asylum seekers and be the liaison between the government, NGOs, and asylum seekers. As part of this role, UNHCR has tried to connect SGBV survivors to the very few services available on the islands. UNHCR officials meet arriving boats and immediately provide asylum seekers with basic information about their rights. UNHCR staff also use that opportunity to direct any asylum seeker who has recently experienced sexual violence or exploitation to tell the authorities as soon as possible. Although it is important to tell survivors how they can seek help, this request is unrealistic. A social worker in Lesvos said, “How do you expect a woman or young girl to step up in public and talk to authority figures they don’t know about the most terrible things they have been through—especially when they are often traumatized for other reasons as well? Do you really think after being smuggled through Iran and Turkey that they are automatically going to trust people in positions of authority?”

Refugees International spoke to an Afghan woman who had arrived two days before with her husband and two children. “I remember them [UNHCR staff] telling us a lot of things about what would happen next and what we should do, but I couldn’t pay attention. There was so much going on and I worried about my children, who were still terrified from the boat trip we took in the middle of the night.”

UNHCR and government authorities should collaborate to hold regular, well-publicized information sessions for asylum seekers—especially women. Facilitators need to provide examples of SGBV and clearly explain how asylum seekers can report incidents of violence, abuse, and exploitation. UNHCR and the Greek government should also partner with legal aid practitioners to provide “know your rights” trainings to asylum seekers so they know what legal recourse they have, if any, following an incident of SGBV. Subsequent to these information sessions and trainings, RIC staff and UNHCR should offer opportunities for women and girls to meet individually with service providers in safe locations. These spaces should be welcoming and confidential, allowing survivors to share information without risk of becoming re-traumatized.

Lack of Capacity

After arrival, each asylum seeker must undergo a medical screening by a Greek doctor contracted specifically for each RIC. These screenings could provide an appropriate circumstance for survivors of SGBV to disclose their experiences. They could then be connected to the very limited medical and psychosocial support services available on the island until being transferred to the Greek mainland, where more services are available. However, the Greek government has not allocated nearly enough doctors to conduct these screenings in a timely manner or conduct thorough examinations. NGO representatives also told Refugees International they are not confident that staff working in these roles have training in how to work with vulnerable people and survivors of SGBV.

In Samos, one doctor serves 7,000 people. Alone, he is able to conduct screenings only three to four months after an asylum seeker has arrived and has no time to engage meaningfully with an individual. This circumstance also means that—in Samos, but also in Lesvos and Chios, where there is a similar shortage of staff, given the number of residents—asylum seekers are usually unable to see a doctor for anything other than emergencies. In those cases, RIC doctors refer the patients to local island hospitals, which are also overwhelmed.

Even the few NGOs dedicated exclusively to preventing and responding to SGBV are entirely under-resourced relative to the needs. For example, there is only one organization with specific SGBV expertise on Lesvos. Previously, its staff could provide basic counseling to survivors who reported within six months of an incident. Now, with a population on Lesvos of more than 30,000 people, its staff can serve only those asylum seekers who report within three months of an SGBV incident.

Lack of Interpretation

Language barriers are another major challenge for asylum seekers seeking to disclose incidents of SGBV and access necessary services. Virtually none of the government authorities, medical professionals, UN staff, law enforcement officers, counselors, border patrol officers, NGO staff, or other personnel on the islands speak the asylum seekers’ languages. Most of them lack knowledge of languages from even the most common refugee-producing countries, such as Afghanistan and Syria. Although the Greek government contracts for interpreters to help provide some essential services, such as asylum interviews, several service providers assisting asylum seekers on the islands indicated that the quality of this interpretation is questionable.

Furthermore, many of the service providers on the islands—particularly small NGOs with limited budgets—do not have interpreters on staff. In Lesvos, where asylum seekers account for one-fifth of its residents, the result is that a significant portion of the population cannot communicate easily with service providers and the host community. For example, if a Syrian woman who needs help approaches the police station, even in Mytilini, the capital, it is likely she will be unable to communicate with the officers. In such cases, some service providers and government entities attempt to find interpreters to help. However, women are often expected to acquire their own interpreter. For a woman disclosing sensitive information she wants keep confidential, bringing an interpreter from her own community is often out of the question.

The GAS has even rejected an asylum seeker because it claimed it could not find a Portuguese interpreter. It is not surprising, then, that often there is no interpretation at all for some less common languages, such as Lingala and Tigrinya.[11] Representatives from an NGO in Chios spoke about several SGBV survivors who could not obtain care from the local hospital because they could not communicate with the medical staff there.

Clearly, securing adequate and quality interpretation is a constant struggle for all of those on the islands. For women and girls, the lack of interpretation assistance often cuts off their ability to access the protective services many of them so desperately need. Every RIC, government agency, international organization, and NGO should make the recruitment and retention of qualified interpreters a top priority.

Fawzia* is not sure how old she is. Nor does her daughter with whom she traveled to Greece. What Fawzia does know is that she is not safe living in the Olive Grove, an overflow area outside of the official Moria reception and identification center (RIC) that is home to more than 10,000 asylum seekers.

Fawzia and her adult daughter left Iran in 2018 when the Iranian government threatened to deport them back to Afghanistan at a time of major human rights abuses and insecurity there. Although Fawzia has lived through decades of conflict at home in Afghanistan, she could not safely return and no longer even had a home there.

Fawzia and her daughter decided to flee from Iran to Turkey, which is also an unwelcome place for Afghan asylum seekers. From there, they took a boat to Greece.

“It was dark, it was cold, and it was so crowded. I don’t know how to swim, but at least my daughter was with me,” she said of the harrowing boat trip.

Fawzia and her daughter are two of the almost 60,000 “new arrivals” who came to the Greek Aegean islands in search of asylum in 2019. They are now living on the cold ground in a camp- ing tent in the Olive Grove. Fawzia has several health problems and can barely walk, but she has no access to medical care. Because of dangers in the camp, her daughter fears leaving her by herself. Despite that, she often must leave her mother to wait in lines for several hours inside the nearby Moria reception center to pick up basic necessities and food, which is sometimes barely edible.

“We can’t get anyone to help us and we are alone, just the two of us. We are given no informa- tion about what is next,” her daughter said.

When asked about the future, Fawzia remarked, “I definitely did not expect to spend my later years living in a tent on the ground. I’m too old for all of this. If I had known that Europe was so awful…I don’t know. Maybe I will die in this camp.”

*Refugees International is using a pseudonym to protect the identity of the asylum seeker.

Assistance for SGBV Survivors

In the absence of an adequate response from the Greek government, NGOs have stepped in to provide some assistance—such as basic counseling, psychosocial support, and emergency medical care—for SGBV survivors. However, such assistance is insufficient. Moreover, asylum seekers on all three islands told Refugees International that it is difficult for them to access accurate information regarding what services are available and which organizations do what.

There are approximately 30 NGOs operating on Lesvos, a majority of which were created within the last five years as a result of the increase in migration and the lack of government capacity to respond. However, many asylum seekers seem confused about the NGOs’ roles. Accurate mapping of services is a challenge among the organizations themselves, let alone for asylum seekers who have significantly less access to information. UNHCR has general knowledge about all of the NGOs and works closely with the Greek government. It is well placed to regularly map the services available and should share the information it gathers with NGOs, government partners, and, most important, asylum seekers. This type of mapping will improve referral pathways.

In contrast to the large number of NGOs on Lesvos, there are far fewer organizations operating on Chios and Samos. Although this fact might make coordination easier, the result is a dearth of services. On islands such as Symi, neither NGOs nor UNHCR have any presence.[12] The lack of assistance on some islands underscores how urgent it is that the Greek government discontinue its containment policy and instead allow asylum seekers the freedom to move to find better conditions.

Vulnerability Assessments

“Vulnerability” assessments were intended to identify asylum seekers who have needs that cannot be met on the islands and/or are particularly susceptible to violence, trafficking, medical emergencies, and so on. They were an explicit exception to the containment policy. Under Greek law, “vulnerability” has a precise legal definition that includes asylum seekers who fall under several categories.[13] At the time of Refugees International’s visit, when the Greek authorities designated an asylum seeker as “vulnerable,” that person’s identity card was “opened” and the geographic restriction—the policy that requires asylum seekers to remain on the islands—was lifted.

In theory, this procedure helped to address the needs of SGBV survivors by allowing them access to better services on the mainland. It was also designed to decongest the hotspots and move vulnerable women, girls, and children to safer locations. In practice however, not enough people have benefited from this exception to the geographic restriction. There is a huge shortage of staff, which at one point led to a three-month period in which no vulnerability assessments at all were conducted on Lesvos. Also, the rules and procedures surrounding the vulnerability interviews change frequently. As a result of a new asylum law that the Greek government is beginning to implement in early 2020, even the vulnerability criteria are changing. Moreover, according to the new law, vulnerability no longer lifts the geographic limitation.

This severe staff shortage and associated inconsistency in conducting vulnerability assessments was immediately evident when the Refugees International team walked around the camps during its late 2019 visit. The team met many asylum seekers, especially women, who should have qualified as vulnerable. Instead, many women in these circumstances are “missed.” The number of single mothers with children, disabled asylum seekers, and elderly women living in areas with no shelter, electricity, running water, or even latrines is disturbing—and these are the ones who visibly meet the legal criteria for being vulnerable. There are thousands whose vulnerabilities are not visibly apparent and languish in these camps with no assistance or protection.

Providing the protection that women and girls desperately need when they arrive in Greece is contingent on the Greek government committing significant resources to hiring more staff for conducting quality vulnerability assessments. The RICs are in urgent need of more doctors, psychologists, and social workers to conduct these evaluations. A social worker from an NGO in Lesvos explained that the problem is not a lack of quality: “Some of the government-employed staff are very good, and of course Greece has many qualified people,” she said. “It is really about quantity at this point. We can’t keep up.”

The Greek government needs to dramatically grow the Hellenic Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the department responsible for managing the vulnerability assessment process on the islands. Until now, the government has had challenges in filling advertised jobs for civil servants to work with asylum seekers on the islands. The government should address this challenge by offering above-average salaries and recruiting recently licensed professionals. Moreover, even as it continues conducting vulnerability assessments to ensure that asylum seekers can access the specialized services they need, the government should immediately end its containment policy. Freedom to move to the mainland should not be linked to vulnerability. Asylum seekers should undergo the asylum procedures on the mainland, where overcrowding and insecurity are less severe.

One director from an international NGO remarked, “The overcrowding is the basis of everything. The poor sanitation, the lack of shelter, so many of the medical problems—none of them will go away unless the severe overcrowding is urgently addressed.”

Unaccompanied Children

The proportion of unaccompanied children (UAC) asylum seekers in Greece has reached distressing levels. As of January 2020, there were just over 5,300 UAC registered in Greece and awaiting their asylum decisions or reunification with close family members in other parts of the EU. Given the large numbers of UAC—children who have fled their home countries and are living in Greece without their parents—the current systems in place to protect and respond to their needs are grossly inadequate. Throughout Refugees International’s field mission, NGOs repeatedly highlighted how dangerous it is for UAC to be waiting in Greece, especially on the islands. At least 2,000 UAC are currently waiting there.

The large numbers of UAC in Greece, including at least 392 girls, represent one of the most pressing concerns for the entire humanitarian community. Even the Greek government recognizes the gravity of the situation. A severe shortage of guardians, extremely limited safe accommodation, difficulties in applying for family reunification, and a high risk of exploitation through smuggling and/or trafficking all create acute challenges for UAC in Greece.

Guardianship

When Frontex intercepts boats, agents register each asylum seeker, including children. According to NGO and UNHCR staff, border authorities have registered minors as adults because many children either did not have the accepted identification documents or were unaware that they should present them. Faced with limited time, the authorities have made rushed—sometimes incorrect—judgments. This seemingly minor technicality actually has significant repercussions. Foremost among them is that children registered as adults will live with adults and receive no specialized assistance.

For those UAC registered as children traveling alone, the Greek authorities are supposed to assign each one a temporary legal guardian, usually a social worker who would be contracted by the Greek government. The role of the guardians is to help UAC with administrative procedures and ensure they have adequate shelter, medical care, and protection. The Greek government has yet to take up this responsibility, however. Instead, for the last few years, an NGO has dedicated its own staff to act as guardians, and there are far too many children who need assistance for this program to be as effective as it needs to be.

The situation on Lesvos is instructive. The island is on the front line of the migrant and refugee crisis in Greece, and receives the majority of those seeking refuge in the country. At the time Refugees International visited Lesvos, there were only two guardians for the 1,200 UAC on the island. According to a former guardian on Lesvos, each guardian can handle a caseload of 20 children at most at any one time. She went on to explain, “With two guardians, that means that at least 1,160 children are left to navigate the complicated asylum process alone and are really left to the mercy of an increasingly hostile environment.”

The circumstances subsequently have become even more dire. After Refugees International’s visit, NGOs on Lesvos informed the team that this NGO-led program of assigning guardians has been officially discontinued. At the time of writing this report, there is only one guardian for extremely urgent cases as a transitional measure before the project stops completely.

Although the situation on Lesvos may be the most acute, it reflects the dismal conditions confronting UAC across Greece. The “Guardianship law” passed in 2018 requires each UAC to have a legal guardian. The government has twice delayed full implementation of the law even though implementation is needed to comply with legal obligations. The law is now scheduled to enter into full force by April 2020. To properly care for the current national caseload of 5,300 unaccompanied children, the Greek government will need to hire upwards of 225 new guardians. This step is essential; the shortage of guardians is only one of the challenges however. Even if there were a sufficient number of guardians on staff, the lack of services on Lesvos—and indeed across the country—would significantly limit their effectiveness. Therefore, the government must also deploy additional staff and funds in key sectors, such as pediatric health and education, to ensure that guardians have the resources required to meet the needs of these vulnerable children.

Insecure Accommodation

At the end of 2019, 1,809 UAC were living inside the official RICs. UAC should reside in sex-segregated trailers, but currently there is not enough space in these temporary structures. In Samos, female UAC are supposed to live in a separate ISO box near the RIC police station for their security. The container has space for eight people. However, at the time of Refugees International’s visit, 20 girls were crammed inside. As the number of UAC continues to rise, the remaining girls take turns sleeping on the concrete outside of the police station—the only place they feel relatively safe. A social worker who works with UAC said, “In my opinion, UAC girls should not be on the islands for more than a week—it is very possible many of them have been trafficked. We don’t track the numbers, but girls always disappear, and no one has any idea what happens to them.”

The National Center for Social Solidarity (EKKA)—the Greek government agency responsible for child protection—reports that 3,492 UAC are living outside of the RICs. Some of these UAC live in apartments with others or in squats. Others survive in the streets, especially in Athens. A large number live in the squalid and unsafe overflow areas outside of the RICs. These children tend to move frequently between different types of accommodation.

In the short term, EKKA should urgently secure safe accommodation for all UAC, especially for the approximately 400 female UAC, who are at heightened risk of exploitation. In the longer term, the Greek government should build appropriate shelters as outlined in the new “No Child Alone” initiative described in further detail below. EKKA should also use the supported independent living (SIL) program for children when it is safe and appropriate. This initiative is one in which some UAC ages 16 to 18 live together in apartments. The Greek government covers their basic needs and ensures the appropriate level of guardianship and supervision.

Family Reunification

Thousands of UAC have traveled to Europe to reunite with family members already in other EU countries. The family reunification process requires significant documentation and the ability to navigate a complicated bureaucracy. Legal aid providers generally help UAC complete this paperwork. Once again, however, limited capacity severely hinders this process.

In Lesvos alone, legal aid providers estimate that at least 600 UAC have legitimate family reunification cases but no legal help. Rather than making the process simpler, EU countries are adding cumbersome requirements. For example, Germany—the primary recipient of family reunification claims—has changed its procedures so that children must lodge their application within three months of arrival in Greece rather than within three months of full registration. This policy change has resulted in hundreds of denied requests for family reunification.

Best Interest Process

When making decisions on behalf of UAC, it is important to undertake the “best interest” process—comprising procedures followed by qualified professionals, based on Article 3 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)—that prioritize the best interest of the child.[14] In Greece, NGO social workers conduct best interest assessments, which include interviewing the child and writing an assessment recommending a course of action for their protection.

The best interest process should ensure that children who want to reunite with legitimate family members can do so if the situation is safe and their family members are prepared to care for them. A social worker noted, however, that the requirement to complete a 40-page “Best Interest Assessment” (BIA) form is “totally unrealistic in an emergency setting such as Greece. They are making it impossible to assist all of the children who need to get out of the camps and be with their parents.” This issue means that UAC remain at risk in the hotspots for much longer than necessary. According to one lawyer, “If receiving countries made the process easier, our shelters would be empty, and kids would be with their families.”

European countries need to simplify the family reunification process. Countries such as Germany, which allow only short windows for lodging family reunification requests, should review cases even if the families miss the application deadlines. They should even consider removing deadlines altogether. EU countries hosting family members of UAC should understand that, especially on the islands, service providers are overstretched and cannot always meet stringent timelines.

Danger of Smuggling

Frustration with this process and lack of assistance leads UAC to leave Greece on their own. UAC increasingly resort to using smugglers to reach their parents rather than wait out the flawed and lengthy process of official family reunification. NGOs told Refugees International that about 150 UAC have left Moria over the last few months, and no one has been able to locate them in Greece; it is assumed that they used smugglers to get to other countries.

A UN staff member recounted a recent case of a 17-year-old Afghan boy whom police found in the back of a truck in northern Greece, having died of suffocation. Because both of his parents were dead, he had a pending family reunification request to join his grandmother in Germany. The process was taking so long he decided his only choice was to try to get to Germany on his own.

Fewer UAC will be tempted to leave Greece on their own if the government hires guardians who can assist them in all matters, including submitting family reunification requests. These guardians should also be responsible for tracking the number of disappeared UAC so policymakers have an accurate understanding of the extent of the problem.

“No Child Alone”

To address these explicit protection risks and the extreme lack of basic services for UAC in Greece, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced a “No Child Alone” plan in November 2019. The prime minister referred to the issue of UAC as “a wound of the migrant crisis that we can heal immediately…” The plan commits the Greek government to build new facilities to provide long-term accommodation for 4,000 UAC. This measure is important. Even if many UAC are reunified with family and/or accepted for further processing in other EU countries, more of them will continue to arrive and need safe shelter. As envisioned, these accommodation centers would also provide food, education, medical care, and some limited psychosocial support to UAC until they can reunify with their families or integrate more permanently in Greece. No Child Alone also puts the responsibility on the Greek government to provide the necessary legal help to children who want to reunite with family members in other parts of the EU.

The plan is a significant step in the right direction. If implemented successfully, it could be used as a model for how to treat asylum seekers in Greece more broadly. Although overwhelmed by the numbers of asylum seekers and refugees, the government recognizes that UAC are among the most vulnerable in Greece and that it is legally responsible for their care and safety.

Even with new commitments made by the Greek government to care for UAC through the No Child Alone policy and the Guardianship law, Greece alone should not be responsible for caring for such large numbers of at-risk children arriving in Europe. In both October and November 2019, the Greek government asked all of the other EU member states to share in the responsibility by taking in 2,500 to 3,000 UAC. Although not a huge burden for those 28 countries, only one responded. Further, Greece cannot make such requests as merely a political posture. The Greek government should be prepared to work cooperatively with EU member states to identify those children appropriate for further asylum processing outside of Greece. This approach will ensure that when other states do finally agree to relocate UACs, the process will be smooth, efficient, and successful.

Frustration with the lack of European solidarity on this issue is palpable on the Greek islands, where so many UAC are stuck in filthy, unsafe conditions. A volunteer from France in Samos remarked, “If you give these kids a chance at life, they will be the biggest supporters of your country. But if this situation continues and European countries continue to deny these children protection, you are creating traumatized young people whose problems Europe will have to deal with later anyway.” A staff member from a medical NGO went further: “We are crippling people for life.”

Conclusion

Asylum seekers currently live in inhumane and degrading conditions, especially in the Greek hotspots. Violence, medical issues, and mental health problems are exacerbated by Greek government policies and the lack of sufficient investment in infrastructure and staff. Women, girls, and UAC are particularly vulnerable to violence, abuse, and exploitation. For so many people who expected to find safety and dignity in Europe, they have found insecurity and misery instead. Five years on from the height of arrivals in 2015, there is no excuse to have such a broken, overstretched system in place. As one NGO staff member put it, “We are going into the fifth winter now and we are talking about the same f—ing sleeping bags.” Greece must do better; the EU must do better.

The lessons Europe learned in the wake of World War II gave birth to international refugee law and institutionalized the principle that states have a responsibility to protect those fleeing conflict and persecution. The way that asylum seekers currently live in Greece is entirely avoidable and threatens to undermine the entire principle of international protection. In January 2020 at a meeting in Washington, DC, the new Greek Prime Minister Mitsotakis stressed that the country has turned a corner and is now a new Greece. He declared, “It is our time to show the world who we are and what we can do!” It truly can be a new Greece if it becomes a leader in refugee reception, integration, and management in a dignified and creative way. Doing so in line with the greatest of European values is as important as ever.

Endnotes

[1] According to the Greek Presidential Decree 220/2007, an unaccompanied minor (UAM) is “any third-country national and stateless person below the age of eighteen who arrives in the territory of Greece unaccompanied by an adult responsible for him and for as long as he is not effectively taken into the care of such a person or a minor who was left unaccompanied after having entered Greece.” For purposes of this report, Refugees International will use the term “unaccompanied children” (UAC) in lieu of UAM to reinforce the fact that such individuals are children.

[2] Although an “exchange” program was agreed on, stipulating that for each Syrian returned to Turkey, the EU would resettle one Syrian from Turkey, Greece had returned only 367 Syrians to Turkey as of December 31, 2019.

[3] Exceptions—some are transferred to other hotspots.

[4] In a forthcoming report, Refugees International evaluates the deeply concerning consequences this law is likely to have for asylum seekers in Greece.

[5] Unless otherwise indicated, Moria (Lesvos), Vathy (Samos), and Vial (Chios) refer both to the formal RICs and the overflow informal tented camps adjacent to the official RICs.

[6] According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, “‘Hotspots’ are facilities set up at the EU’s external border in Greece and Italy for the initial reception, identification and registration of asylum seekers and other migrants coming to the EU by sea. They also serve to channel newly-arrived people into international protection, return or other procedures.” The European Commission formulated the hotspot approach in April 2015 in response to large numbers of arrivals. There are currently five hotspots in Greece on the islands of Lesvos, Chios, Samos, Kos, and Leros.

[7] For the purposes of this report, Refugees International will use the terms gender-based violence and sexual and gender-based violence interchangeably.

[8] UN Committee against Torture (UN Doc. CAT/C/GRC/CO/7).

[9] Her name has been changed at her request because she wishes her identity to remain confidential.

[10] A total of 2.3 percent of asylum applications in Greece are made on behalf of people from the DRC, a country known for its high levels of SGBV, especially in conflict zones.

[11] Lingala is a Bantu language spoken throughout the northwestern part of the DRC and a large part of the Republic of the Congo. It is spoken by about 70 million people in the Great Lakes region of Africa. Tigrinya is spoken in Eritrea and Ethiopia.

[12] Because there are no NGOs on Symi and it is not a hotspot, asylum seekers who arrive there are regularly transferred to other islands where their asylum claims can be processed. Because of a lack of any infrastructure dedicated to asylum seekers, migrants who arrive from Turkey have been sleeping in the local police station or on the streets.

[13] According to “Greece: Law No. 4375 of 2016 on the Organization and Operation of the Asylum Service, the Appeals Authority, the Reception and Identification Service, the Establishment of the General Secretariat for Reception, the Transposition into Greek Legislation of the Provisions of Directive 2013/32/EC,” the categories of vulnerability are as follows: unaccompanied children; persons suffering from disability or a serious or incurable illness; pregnant women/new mothers; single parents with minor children; victims of torture, rape, or other serious forms of exploitation; elderly persons; victims of human trafficking; and minors accompanied by members of extended family.

[14] Article 3 states, “In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”