Lebanon at a Crossroads: Growing Uncertainty for Syrian Refugees

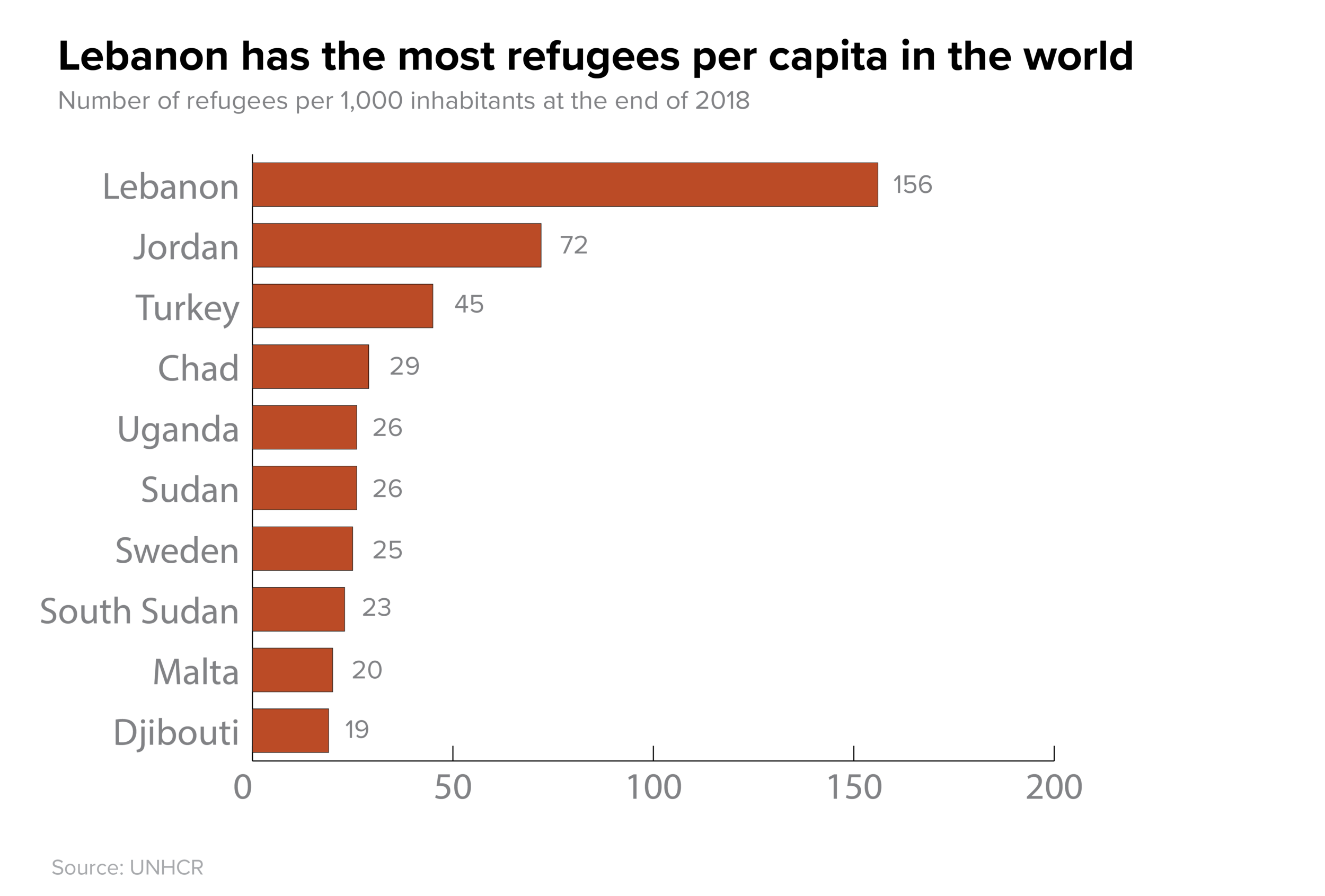

Nine years into the Syrian conflict, nearly 1.5 million Syrian refugees are currently living in Lebanon, of whom about 950,000 are registered with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). With a population estimated at around 6 million, Lebanon is host to the largest number of refugees per capita in the world. This massive influx has posed immense challenges to this small country, which lacks the adequate resources, infrastructure, and political will to respond to refugees’ needs. International and regional donors—that provided more than US$7 billion to the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP) between 2012 and 2018—have helped Lebanon cope with the challenge. However, donors’ commitments have gradually receded. Only 52 percent of the US$2.62 billion required to assist refugees and host communities have been met for 2020.

Predictably, as refugee flow intensified, Lebanon’s initial welcome of Syrians increasingly waned. In host communities, most of which already suffer from poverty and marginalization, resentment has been on the rise. According to UNHCR, more than 60 percent of Syrian refugees are settled in north Lebanon and the Bekaa Valley in the east—two of the most deprived regions in the country. Many Syrians live in extremely dire and vulnerable conditions.

Currently, most refugees are denied legal residency or the right to work. Syrians can work legally in only three low-skilled sectors—agriculture, construction, and cleaning. As a result, many find jobs in the informal sector, where conditions are precarious. Equally worrying, human rights abuses against Syrian refugees have multiplied, including house demolitions, collective evictions, curfews that single them out, or arrests because they lack extremely hard-to-get residency permits. Lebanese officials often have exploited the refugee presence for political gain. Some, including members of the government, have made racist and xenophobic declarations against Syrians. In 2018, Lebanon began organizing the return of Syrian refugees despite the many risks they face back home. Also, based on a decision to expel any Syrian who entered Lebanon informally after April 24, 2019, the country’s General Security Organization (GSO) deported hundreds of Syrians without referring them to a judge. Overall, both official and informal pressures to force Syrians out the country have increased.

In recent months, the situation of Syrians in Lebanon has become even more precarious because the country faces one of the direst economic and financial crises in its recent history. In late October 2019, massive popular demonstrations led to the resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri. Through the support of the Shiite militant group Hizbollah and its allies (known as the March 8 coalition), Hassan Diab was appointed prime minister in December 2019. More than three months into the protests, Diab formed a new government whose members are largely perceived as affiliated with parties of the March 8 coalition. It remains uncertain whether the government will be able to implement much-needed reforms or garner critical international support to address the ever-worsening crisis.

Lebanon is at a crossroads. Violence is rising, as is the use of excessive force against protestors and activists. The increasing drift toward repression threatens to further destabilize the country and undermine the situation of all people in Lebanon, including refugees. The current crisis has largely overshadowed the issue of Syrian refugees and pressures for their return. However, such a return will almost certainly be a priority for the new government. Despite its massive challenges, the crisis should serve as an opportunity to radically change Lebanon’s approach toward refugees and its most impoverished citizens.

Recommendations

To Lebanon:

The new Lebanese government should do the following:

- End discriminatory practices against Syrian refugees, such as collective evictions and curfews.

- Ease restrictions on access to legal residency for Syrian refugees, including abolishing the sponsorship system.

- Regularize the informal Syrian workforce in sectors like hospitality and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and expand work permits to other sectors in which Lebanon suffers from a major labor shortage, such as nursing.

- With the support of international partners, develop a job creation program that includes Syrians. Allocate a significant percentage of these newly created jobs to Syrian refugees. Grant legal residency and work permits for the Syrians selected for these jobs.

- Dedicate special efforts and funds to boost the local economies of marginalized areas that host significant numbers of refugees, such as the Bekaa Valley and northern Lebanon.

- Ensure that any future organized return takes place through a UN-led and monitored mechanism.

Lebanese politicians should do the following:

- End all racist and xenophobic rhetoric against refugees.

The General Security Office should do the following:

- Stop unlawful deportation of Syrians and refer all of those arrested for illegal entry to the judicial authorities.

- Halt the unsafe and premature organized return of Syrian refugees as long as their safety inside Syria cannot be guaranteed.

The Lebanese armed forces and internal security forces should do the following:

- Stop the use of excessive force against protestors and activists, as well as all forms of harassment and acts of intimidation against Syrian refugees, including demolishing shelters and arresting people for not being legal residents.

- Hold accountable any of their members who perpetrate human rights abuses against Lebanese citizens and refugees.

The European and U.S. governments should do the following:

- Continue supporting the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan and fill the funding gaps estimated at US$1.25 billion, to enable the humanitarian community in Lebanon to respond to needs.

- In coordination with local actors, the UN, and NGOs, focus on sustainable livelihood opportunities targeting the most vulnerable, and dedicate special funds to marginalized areas that host a large majority of Syrian refugees, including in the Bekaa Valley and north Lebanon.

- Press Lebanon to uphold its commitment to respect the human rights of all people, including protestors and refugees.

- Significantly increase the resettlement of Syrian refugees from Lebanon to the United States and European countries.

Donors, international institutions, UN agencies, and NGOs should do the following:

- Work with the Lebanese government on initiatives that create job opportunities; a significant portion of these jobs should benefit Syrian refugees, to whom the Lebanese government should grant residency and work permits.

- End programs that provide vocational and skills trainings for both refugees and Lebanese citizens in fields in which employment prospects are virtually non-existent.

Research Overview

A Refugees International team traveled to Lebanon in October 2019 to investigate the conditions of Syrian refugees and the pressure for their return to Syria. The team conducted interviews with representatives of UN agencies, Lebanese and Syrian nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), as well as Syrian refugees in south Lebanon and inside informal settlements in northern Lebanon. During the team’s time in Lebanon, massive popular protests swept the country, and roadblocks prevented the team members from traveling to the Bekaa Valley. Refugees International interviewed NGO representatives and some refugees in the Bekaa Valley by phone. Finally, to understand refugee-related issues among protestors, Refugees International observed the protests for several days and interviewed protestors and activists.

Background

For the past two decades, Lebanon has been gripped by political division, a recurrent political stalemate, and intermittent violence. Three decades after the end of its 1975–1990 civil war, the country still suffers from a dilapidated infrastructure and lacks adequate public services, including water, electricity, transportation, and sanitation. The third most indebted country worldwide, it now faces one of the most acute financial crises. For months, banks have been imposing increasingly restrictive measures on depositors, limiting withdrawals of funds and other transactions in U.S. dollars and, to a lesser degree, the Lebanese pound (LBP). These measures remain largely arbitrary and nontransparent, and have led to numerous violent incidents inside banks.

This deteriorating situation led to massive demonstrations in October 2019. The protesters called for the fall of the entire ruling class, whom they held responsible for the economic downturn, widespread corruption, governance failure, and embezzlement of public funds. After nearly two weeks, as massive demonstrations continued and protestors blocked major roads to significantly hamper commuting between regions, Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigned. Backed by Hizbollah and its allies, Hassan Diab was nominated to the premiership. On January 21, 2020, Diab announced a new government after lengthy negotiations and bargaining between the parties allied with Hizbollah. Thus, the new government fails to meet the protestors’ main demand for an independent and non-partisan cabinet.

Because of its dysfunctional state, Lebanon has failed to adopt a strategy that addresses the immense challenges posed by the influx of an estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees. They are dispersed across the country, living in cities, towns, or spontaneously erected tented settlements. The refugee presence is felt most in impoverished host communities that have suffered from decades of the state’s negligence and exclusion. According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), more than 63 percent of Syrian refugees reside in north Lebanon and the Bekaa Valley in the east—two of the most marginalized areas in the country. They have put additional strains on resources, public services, and access to the labor market, thus exacerbating Lebanese-Syrian competition for jobs.

More worryingly, refugees have often borne the blame for many of the country’s woes. Just a few weeks before the protests erupted in October 2019, they were the target of xenophobic media and public campaigns, in addition to demolition of shelters and deportation. For years, they have suffered from numerous human rights abuses and discrimination. However, this treatment is not specific to Syrian refugees. Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, estimated at between 200,000 and 300,000, have for decades suffered from the same fate. Lebanon’s anti-refugee approach is shaped largely by its 15-year civil war, which also partially involved Palestinians.

Today, as the narrative that the war in Syria is winding down and Lebanon’s economy is deteriorating further, Syrian refugees face the risk of being pushed into returning to areas of Syria that still lack the most basic conditions for a safe and dignified life.

Push for Return

As the Syrian conflict intensified, the number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon multiplied six-fold between 2013 and 2014. Today, one in every four people living in the country is a Syrian national. This rapid population growth has created substantial challenges for Lebanon, which already suffers from a weak economy, high unemployment, depleted resources, decaying infrastructure, and ineffective public services. Gradually, the Lebanese welcome for refugees has given way to growing resentment and tensions.

Forced into Illegality

Although a comprehensive strategy to address the refugee challenge was necessary, the Lebanese government, whose members were divided on the war in Syria and the refugees, has failed to agree on a unified response. The government’s inaction created the perception that the situation was unmanageable; thus, Lebanon ended its open-door policy and imposed a range of measures aimed at reducing the number of Syrians in the country. As a result, narrow eligibility, economic barriers, and arbitrary administrative procedures have limited access to residency for most Syrians. The Syrians, however, have had few options: resettlement in third countries has become increasingly difficult, and return to Syria has not been feasible. Ultimately, Lebanon’s policies have forced most Syrian refugees into illegality.

Today, UNHCR estimates that more than 70 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon live there without legal residency. As a Syrian relief worker put it, “even if we wanted to, it is virtually impossible to comply with visa regulations. And when someone does have all the necessary documents, it might take months to get the residency permit, if at all.” Lebanon has largely allowed Syrian refugees, including those with no legal status, to remain in the country. However, authorities have occasionally conducted random identity checks targeting men and have arrested refugees with no legal residency for a brief period, some told Refugees International.

Lebanon is not party to the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, and has mostly relinquished its responsibility to deal with refugees. Officially, Syrians in Lebanon are referred to as “displaced people.” Moreover, the government’s decision in 2015 to instruct UNHCR to halt the registration of Syrians has had a detrimental effect on many of them. It has denied hundreds of thousands of unregistered refugees the support and protection afforded by the UN agency, pushing them into even greater distress.

Unsurprisingly, most experts believe that these more restrictive measures did not decrease the number of Syrians in the country. Instead, the measures have exacerbated the precarious conditions of refugees while reducing the government’s oversight of them. As an academic observed, “The Lebanese government assumes that suffocating measures are likely to push refugees into going back to Syria. The reality is that these policies aggravate refugees’ hardship, but they also render their presence informal. Lebanon doesn’t have information about many of the people residing on its territory.”

Forcing Syrians into illegality largely has become the norm, leaving most with few choices but to bypass the system. “The only way to get by in our daily life is to evade these laws. I have no legal residency, I can’t go to Europe, I can’t go back to Syria! What can I do? Every day I take measures to avoid being arrested. So far, I have been lucky!” said a Syrian refugee who works as a chef in a restaurant in Beirut.

However, bypassing the system comes with many risks and affects almost all aspects of life for Syrians in Lebanon. Often, refugees—especially males—have limited their movement drastically for fear of random identity checks, arrest, or even deportation by security forces. In informal refugee settlements in Akkar in north Lebanon, many refugees told Refugees International that they had not left the camp for weeks. This immobility not only hinders their ability to work to make ends meet, it also prevents access to education, health care, and other basic services, which only fuels a vulnerability cycle. “When these laws and restrictions are adopted, authorities don’t have people in mind. They don’t think of us, refugees, as human beings,” lamented a Syrian doctor living in Tripoli.

To make matters even worse, rules change constantly and often lack clarity. Their implementation is often arbitrary; only those who have some connections and/or financial means can hope to dodge these harsh regulations. The head of a relief organization in the Bekaa Valley said, “Despite having a residency permit, my wife was not allowed to enter Lebanon with our kids—a new regulation now requires the children’s residency to be separate from their parents. We pulled some strings, and the issue was finally resolved. We are lucky, but most Syrians are not.”

No Right to Work

Similarly, an extremely restrictive labor law has pushed most Syrians into the informal job market, where exploitation and low pay are common. Lebanon allows Syrians to work legally in only three low-skilled sectors: agriculture, construction, and cleaning. Work permits in other sectors are virtually impossible for Syrians to obtain. Several refugees working in the informal sector told Refugees International that they were sometimes paid less than a dollar per hour.

Even in those employment sectors allowed by the government, Syrians lack protection; their difficult work conditions are exacerbated by their overall precarious situation with respect to legal residency. In an informal settlement in Akkar, a mother of five working in agriculture—a sector that does not require Syrians to have a work permit—recounted her experience with the owner of land where an informal camp was established. “He also owns a farming land nearby. My 10-year[-old] daughter and I work for him. Some days, we work in the heat for 10 hours or more. He hasn’t paid us a penny for the past 10 months. When I requested my money, he threatened to kick us out of the camp.”

More worryingly, the widespread anti-refugee rhetoric has led to some Lebanese citizens engaging in vigilante behavior. A Syrian refugee living in Qolei’at in Akkar was harassed repeatedly by his Lebanese neighbor when he decided to sell some basic commodities in front of his modest apartment. “My neighbor used to come every day, make racist comments, asking me to go back to Syria and threaten me,” he said. “A month later, she came accompanied by a police officer who raided my small shop, ruined most of the supplies, and forced me to close.” Sadly, this incident is not unusual. Flyers calling on citizens to report Syrians working illegally, Syrian-owned shops being vandalized, anti-Syrian demonstrations, and chants against businesses employing Syrian nationals have been exacerbated by a Ministry of Labor campaign to close such businesses. Moreover, many of these incidents are not spontaneous; they are often instigated by Lebanese officials or politically affiliated media channels. In June 2019, Gebran Bassil, then Lebanon’s minister for foreign affairs and leader of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), posted a video on Twitter showing members of his party protesting in front of a restaurant that employs Syrian workers. “If you love Lebanon… hire Lebanese,” he commented on the video.

According to most interlocutors interviewed by Refugees International, competition for work is the primary source of tension between Syrians and their Lebanese hosts. Undoubtedly, Lebanon’s struggling economy and worsening unemployment have compounded these dynamics. An August 2018 report estimated the unemployment rate to be around 25 percent, and as high as 37 percent among the country’s youth. The situation has deteriorated significantly since that time. The economic and monetary crisis recently led to hundreds of businesses closing. Thousands of people have lost their jobs—if not more—and many employees have reported salary cuts since October 2019. Economists believe that the situation will almost certainly worsen. The lack of prospects for improvement has even pushed some citizens into desperate measures, such as suicide or self-immolation.

There is no easy fix for Lebanon’s unemployment crisis—it would require extraordinary domestic efforts and international support to address. However, donors and implementing organizations can help alleviate the situation, especially for those most vulnerable. At these challenging times for Lebanon, donors, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and UN agencies should focus on livelihood opportunities, paying special attention to areas that host significant numbers of refugees.

Even though the right to work is a fundamental human right that should not be denied, it is unlikely that Lebanon will grant it to most Syrians (or Palestinians) because of its ailing economy. However, international donors and institutions such as the World Bank should incentivize the Lebanese government to ease its restrictive labor policy toward refugees. They should press Lebanon to expand refugees’ right to work to sectors in which significant numbers of Syrians are already employed informally, such as the hospitality and NGO industries, and also use the Syrian workforce in sectors that suffer from labor shortages, such as nursing. Finally, initiatives aimed at creating jobs should include refugees. With international support, Lebanon should agree to allocate a significant percentage of newly created jobs to Syrian refugees. Lebanon should commit to grant residency status and work permits to those targeted by these initiatives.

More broadly, donors and implementing organizations should significantly rethink their approaches to ensuring sustainable livelihood projects that respond to the needs and qualifications specific to each region, in coordination with local actors and the private sector. They should avoid projects and trainings that leave many with newly acquired skills but no prospects for work. Echoing the frustration that many people in local communities relayed, a representative of an international NGO said that “Donors like trainings because this kind of activity provides specific and significant numbers that they can then turn in to their governments. They like quick fixes. But the numbers don’t reflect reality. In the past decade, millions of dollars have been spent on training. What changed? We left tens of thousands of trainees unable to find jobs, despite their newfound skills. We only increased their frustrations. There is something fundamentally wrong with this approach.”

Deprived of Protection

Not only has Lebanon failed to address refugees’ needs, it also has relinquished its duty to protect them. Successive governments have resorted to politicizing humanitarian issues involving refugees, and officials have repeatedly used refugees to deflect from their own responsibility for the country’s long-festering crisis. One party in particular—the Christian Free Patriotic Movement (FPM)—and its leader, Gebran Bassil, have escalated the situation to dangerous extremes, repeatedly exploiting their constituency’s existential fear of the mostly Sunni Syrian refugees. “We have established the concept for our Lebanese belonging, which is above any other belonging,” he tweeted in June 2019. “We said that it was genetic and that is the only explanation for our similarity and distinction, for our ability to sustain and accommodate together, for our flexibility and strength, our ability to integrate and be integrated, for our refusal [for Lebanon to be a place for] any displacement or refuge.”

At the local level, the government’s hostility has allowed for abusive and discriminatory measures against Syrians, such as collective evictions and curfews. According to a 2018 Human Rights Watch report, “At least 13 municipalities in Lebanon have forcibly evicted at least 3,664 Syrian refugees from their homes and expelled them from the municipalities, apparently because of their nationality or religion, while another 42,000 refugees remain at risk of eviction.”

Lebanon not only considers refugees as an economic burden, it also perceives them as a security and political threat, deemed a destabilizing factor that impacts the country’s fragile sectarian balance and security. Historically, many Lebanese citizens and officials have been wary of refugees, recalling the country’s 15-year war that partially involved Palestinian refugees. In addition, the Syrian regime’s decades-long divisive and destabilizing interference in its Lebanese neighbor’s affairs have made the relationship with Syrian refugees even more tenuous. Finally, Lebanon has seen some violent spillovers from the Syrian war. Spillovers from that war—a bloody 2014 confrontation between the Lebanese army and Syrian extremist fighters in the northeast and a series of suicide attacks between 2013 and 2016, some of which involved Syrian (albeit non-refugee) nationals—have only amplified suspicion regarding these refugees.

As a result, the task of regulating the presence of Syrians in Lebanon is conducted mostly by the security and military apparatus. Security forces have relied broadly on punitive methods, including regular raids on informal refugee settlements, arrests, intimidation, and even torture of some detained Syrians. This security-driven approach has served to justify harsh and repressive measures that disregard humane considerations.

For instance, in the summer of 2019, the Lebanese army invoked a 2004 construction law that prohibits some types of construction, with the aim of forcing the demolition of concrete shelters in informal refugee settlements in Arsal, a border town in northeast Lebanon. Not only was the decision implemented exclusively against Syrians despite widespread illegal construction across the country, it also left thousands of refugees—mostly children—unprotected in the face of harsh weather conditions. In a previous winter storm, many of them had seen their tents and belongings flooded and washed out. As a UNHCR senior official explained, “When refugees built these shelters with the support of NGOs, their intention was not to break the law. They were seeking minimal measures to protect themselves and their families from the elements, including strong winds and cold.” To avoid the army’s raids on the camps, most refugees destroyed their shelters with their own hands.

Similarly, between May 21 and August 29, 2019, Lebanon’s General Security Organization (GSO) deported more than 2,700 Syrians. This decision was based on an earlier announcement by the Higher Defense Council—an inter-ministerial body in charge of national defense policy—that refugees who entered Lebanon “illegally” after April 24, 2019 would be deported. However, several legal and human rights experts noted the unlawful nature of these deportations, with little consideration for deportees’ safety. “While Lebanon has the right to protect its borders from illegal migration,” explained a legal expert, “a judge should issue a deportation decision. The court should consider safety risks and other protection needs. If it threatens one’s life, deportation is in violation of international law.” Even more concerning is the fact that authorities denied those who were deported legal representation and the means to prove they had entered the country before April 2019.

Refugees are not the only target of the government’s heavy-handed security measures. These measures reflect a wider trend: the country’s drift toward greater repression. Human rights organizations have reported increasing violations and abuses against Lebanese activists, journalists, protesters, and critics of Lebanon’s government and leaders. More recently, security and military forces have resorted to brutal and unjustified violence against protesters.

Organized Return: Premature and Unsafe

The issue of the return of Syrian nationals is politically charged and highly polemic in Lebanon and beyond. Opponents of the Syrian regime invoke the latter’s brutality and repression, the country’s massive destruction, and the general insecurity in Syria as among the many deterrents for the return of refugees. On the other hand, the regime’s backers see return as a ratification of their ally’s military victory and thus have taken various measures to encourage it. In Lebanon, however, the issue has prompted a rare consensus among an otherwise deeply divided political class. Thus, Beirut has taken direct measures to push for return and has set up so-called “return offices” for this purpose. Lebanese security forces and the Syrian regime’s allies have been mediating for those who have signed up for return and are trying to obtain a security clearance from authorities in Damascus to allow it.

However, the process remains problematic. The Syrian president’s call for refugees to return home notwithstanding, Damascus has adopted numerous measures that have effectively deterred return en masse. The treatment of the internally displaced, continued insecurity, arbitrary laws, detention of some returnees, and conscription have dissuaded the vast majority from setting foot in Syria, as have other barriers. As for the Lebanon-led process, a researcher explained that it remains extremely uncertain. “While some [of those who signed up for return] were cleared by the Syrian security and others were not, the majority was left in limbo, neither cleared nor vetoed,” he said.

Yet it is the returnees’ safety that is of most concern. The situation inside Syria remains very opaque, and independent monitoring of returnee conditions is virtually impossible. There are numerous accounts of detention, interrogation, and even torture of refugees upon their return.

For its part, the UNHCR does not facilitate any large-scale repatriation. However, the agency has been providing support to refugees deciding to return now, including to obtain essential documentation, to help those who return be equipped to re-establish themselves back home. A UNHCR senior official explained that, “Refugees should not be lumped all together as one single mass. It is inappropriate to tell people what to do. Return is an individual choice. UNHCR wants to create the space for Syrians to make their own decisions. We don’t incentivize return. We only make sure that people are well informed and that their decision is based on knowledge. We have a responsibility to equip refugees who take the decision to return to do so in as safe, dignified, and sustainable way as possible. We want to enable them to restart their lives once back in their country.”

In addition, the agency dispatches protection officers to the Lebanese border to observe the return process and ensure, through interviews with refugees, that they are not being coerced into leaving the country. “It is not ideal,” said a Western official, “but UNHCR presence is critical. They are the witness on the ground to ensure that these returns are not forcible.” However, the immense direct and indirect pressure on refugees makes the voluntary nature of many if not most of these returns highly improbable. Unsurprisingly, some activists and relief workers have criticized UNHCR’s role in the repatriation. “Do you think refugees on the border surrounded by Lebanese security, about to go to Syria, would tell a UNHCR officer that they were not forced to leave? The UNHCR is becoming a false witness!” said the head of an NGO.

In short, despite all of the pressure and the fact that almost all Syrians say that they want to eventually return to Syria, only a small percentage of Syrian refugees have been repatriated. Furthermore, they are unlikely to return to their homes any time soon.

Real numbers remain uncertain. Lebanese authorities claim that nearly 100,000 returned to Syria in 2018. However, many interlocutors believe that Beirut inflates the return figures to encourage the process. UNHCR monitored the return of only half this number between 2016 and 2019. Moreover, even if the war completely recedes in Syria, many of Lebanon’s Syrian refugees are what one of them characterized as “political refugees.” They include fighters, Syrian army defectors, activists, journalists, and even humanitarian organization staff who have worked in Syrian opposition-controlled areas, and whose safety would be at risk under Syria’s current regime.

Lebanon should refrain from a hasty return process and instead wait for an internationally recognized return mechanism, led and monitored by the UN, to ensure the safety and dignity of returnees. However, this will be possible only with strong and sustainable international support to help Lebanon cope with refugees and the increasing economic stress.

The Role of the International Community

Donor countries have stepped in to help Lebanon cope with the massive Syrian refugee influx. Between 2012 and 2018, their contribution to the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP) totaled around US$7.1 billion. The LCRP is a joint plan between the government of Lebanon and the UN that aims to respond to the needs of refugees and host communities. Because of the immense needs and the country’s meager resources, this assistance was critical to both the refugees and their hosts. A refugee expert explained, “These funds have prevented the deterioration of basic needs and the exacerbation of communal tensions. International support to Lebanon is necessary and should continue.” However, nine years into the Syrian conflict, donor fatigue is increasing. For 2020, 48 percent of the US$2.62 billion appeal for the LCRP remain unfunded.[01]

More broadly, Lebanon has grown increasingly dependent on foreign aid. At the Cedar Conference in Paris in April 2018, international donors pledged US$11 billion in soft loans to boost the country’s economic development.[02] However, Lebanon has been unable to tap those pledges because it cannot demonstrate the credible reforms required by donors. Similarly, the United States and European countries have been instrumental in providing support to the country’s security sector. In March 2018, the European Union (EU) held the Rome II conference in support of Lebanon’s security institutions—the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) and the Internal Security Forces (ISF). In early December 2019, the White House lifted an unexplained hold on US$105 million in military aid.

Western donors, especially those in Europe, seem intent upon preventing new waves of refugees from reaching the EU. They have focused primarily on Lebanon’s stability and have increasingly turned a blind eye to human rights violations against refugees—and Lebanese citizens. The head of a Lebanese human rights organization warned that, “The Europeans’ advocacy for human rights in Lebanon has waned. They even removed it as a conditionality for funding the Lebanese government.”

Lebanon is at a crossroads. The risk of violence is increasing, and international donors play a critical role in helping Beirut mitigate the crisis. However, safeguarding the country’s stability should not be a pretext for maintaining an untenable status quo, which consigns refugees and other vulnerable populations to uncertainty, poverty, and abuse. The urgency of the current economic and financial crisis should not overshadow the needs of those most vulnerable. Thus, the international community should press Lebanon to respect the safety, dignity, and rights of refugees and Lebanese citizens. International and regional donors should continue to provide the much-needed funds to respond to humanitarian needs in Lebanon. They should also prioritize livelihood opportunities, especially in marginalized areas like the Bekaa Valley and northern Lebanon, which host a large majority of Syrian refugees.

Human rights abuses committed by members of security institutions, including those receiving support from Western governments, cannot be ignored. The United States and the EU should urge Lebanese security and military forces to stop using excessive force against protestors and activists, cease all kinds of discrimination and abuses against refugees, and commit to the basic need to hold accountable the perpetrators of human rights violations.

Finally, the United States and most European countries should also acknowledge their own shortcomings. Their anti-refugee policies at home have delegitimized their efforts to protect refugees worldwide. A U.S. observer solemnly inquired, “How can we preach to Lebanon about better treatment of its refugees when we closed our doors in their face?” As Lebanon confronts an increasingly dire situation, the United States and EU member states should prioritize the resettlement of significant numbers of refugees from Lebanon in their own countries.

What Is Next for Syrian refugees?

As Lebanon’s situation deteriorates, refugees are not being spared from the shockwaves of the crisis. Like their hosts, they are suffering from the country’s collapsing economy. The significant inflation and devaluation of the Lebanese pound has substantially reduced people’s purchasing power. “There is a crazy increase in commodities prices. People are starting to reduce their food intake,” said an unemployed Syrian relief worker in a phone interview with Refugees International. “As for me, I have to choose between feeding my family or paying the rent. Debts are just piling up.”

Given the mostly informal nature of Syrians’ employment in Lebanon, it is virtually impossible to assess the impact of the overall labor crisis on Syrian refugees. However, refugees certainly have been affected by the closing of businesses, pay cuts, and employee layoffs. A Syrian refugee lamented,

Since I came to Lebanon, finding a job was not easy, but I always felt I could manage to make ends meet. However, for several months now, it has become almost impossible to get a job—any type of job. I spoke to the owners of many small and medium-sized businesses. All have told me that they are reducing their expenses, and some might have to close soon.

The banking crisis has made things even worse. Restrictions have hampered employers’ ability to pay salaries. They have also affected NGO operations, including providing services, as money withdrawal and bank transfers become increasingly challenging. Despite the economic crisis, only a few refugees have returned to Syria since October 2019.

Lebanese protests have had a mixed impact on refugees. Some Syrians, typically activists, voiced their support for protesters, but the vast majority have mostly kept a low profile. Fear and uncertainty prevail among many Syrian refugees. The memory of violence at home, which ripped them away from everything they had ever had, is still fresh. “We fear from history repeating itself,” one said. In addition, many refugees remain concerned that they could become the scapegoats for Lebanon’s current unrest. “We are very worried,” said a refugee in Beirut. “Anti-refugee slogans have faded. But all it takes is one fiery statement by [Gebran] Bassil to spark anti-refugee sentiments all over again.” In late October 2019, threatening audio messages against refugees circulating on WhatsApp terrorized many refugees, especially those inside informal settlements. In Halba, Akkar, a mother of five, told Refugees International, “I am afraid that something will happen. I can’t sleep at night. My husband and I take turns to watch the tent.”

Still, the Lebanese protests mostly have shifted blame from Syrian refugees to the Lebanese officials and political figures who have genuine responsibility for the country’s dysfunction and collapsing economy. Some protesters have questioned the racist, anti-refugee rhetoric in the country, while voices expressing resentment against refugees mostly have been silenced. Most important, attempts to use refugees as a distraction from the country’s real problems have been unable to gain much traction. Overall, the issue of refugees has been marginal since the protests erupted. Although this trend is encouraging, it is not enough.

This momentum should serve as an opportunity for Lebanon to change its policy toward refugees. Lebanon should acknowledge that the majority of Syrians are not going to return to Syria any time soon. With international support, the country should empower them to increase their chances for return once the conditions are suitable. As a UNHCR senior official explained, “It’s not because people are struggling that they will return. Many other considerations influence their decision. From our experience, the most vulnerable are generally the last to go because they are the most encumbered by debt, lack of education, and feeling incapacitated to restart a life in a country severely affected by war.”

Conclusion

Undeniably, Lebanon faces one of its most challenging crises ever. This crisis has affected all aspects of the country, including the economy, the monetary and banking system, governance, and the security situation. Despite the urgency, Lebanese officials have not adopted any serious plan to mitigate this crisis, and political deadlock has prevailed for months. Fundamental reforms have become Lebanon’s only way out of the abyss. However, as Lebanon tries to mitigate the crisis, neither Syrian refugees nor vulnerable Lebanese should be forced to pay the price. Syrian refugees must not be made scapegoats.

Endnotes:

[01] Email correspondence with UNHCR officials.

[02] The Cedar Conference is also known for its French acronym CEDRE (Conférence Economique pour le Développement par les Réformes et avec les Entreprises)