By Land or By Sea: Syrian Refugees Weigh Their Futures

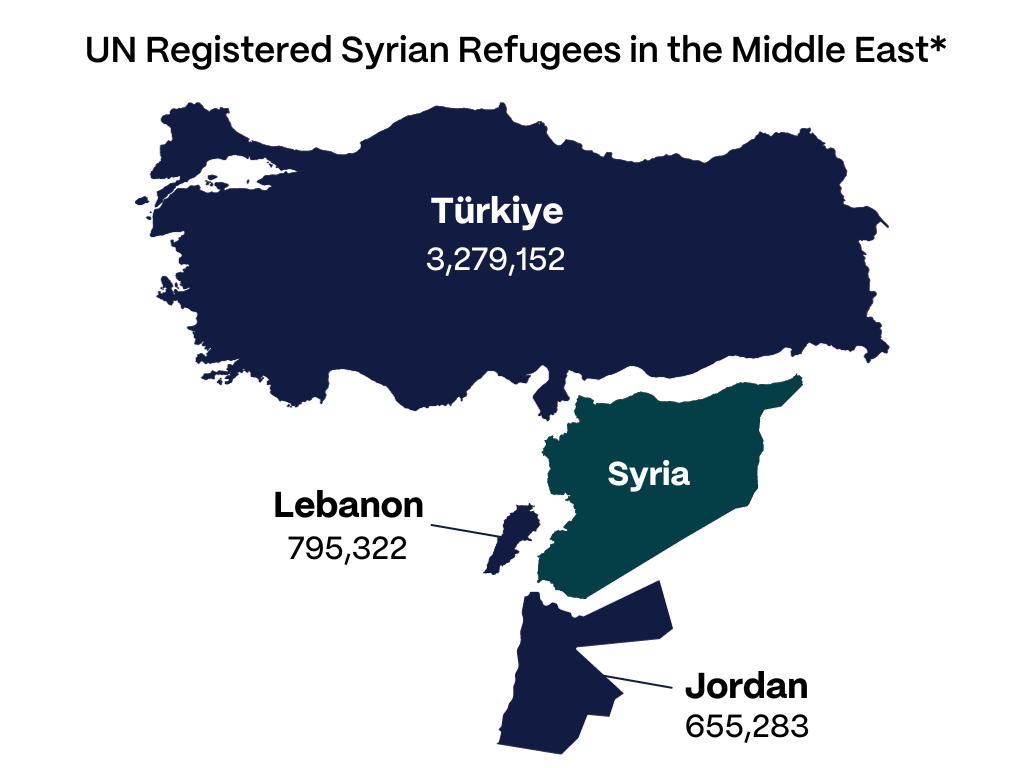

After 12 years of war, nearly 5.2 million Syrian refugees in Türkiye, Lebanon, and Jordan are caught in an increasingly untenable limbo. Host countries are normalizing relations with the Syrian government and are eager for refugees to depart, even though there is no foreseeable prospect of them ever safely returning to Syria. The time has come for a serious global conversation on durable solutions for Syrian refugees—one that acknowledges the impossibility of return and grapples seriously with expanded local integration and global resettlement.

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has clearly articulated that conditions in Syria are not suitable for a safe, dignified, and voluntary return. Regardless, host countries, contending with their own economic pressures, are increasingly normalizing relations with Syria, while simultaneously ramping up efforts to force Syrians to return—even though there is no foreseeable prospect of them ever safely returning to Syria. This is a clear violation of their obligation to the principle of non-refoulement.

The Syrian government does not want Syrian refugees to return en masse but exploits the refugee crisis to pressure neighboring countries to engage more deeply in normalization and reconstruction. Syrian authorities continue to employ forced conscription, reprisals, arbitrary detention, extortion, or enforced disappearances against the Syrian people, including Syrian refugee returnees and deportees. Efforts by Jordan and senior UN officials to secure meaningful safeguards for returnees from the Syrian government have failed. The failure to find a durable solution to the refugee crisis works to the Syrian government’s political advantage by granting it unchecked leverage over Syria’s neighbors.

In Lebanon and Türkiye, security forces are actively raiding and deporting thousands of Syrian refugees, in violation of their legal rights to protection, back to Syria, where some face arrest, extortion, and torture. Syrians remaining in these countries are left to cope with deepening fear and insecurity over their futures. These measures not only threaten refugees’ safety but also undermine the essential work of Syrian NGOs in host countries and in Northwest Syria.

Humanitarian aid is meanwhile declining as donors, fatigued by the protracted response, are turning their focus to more recent crises. The failure of donor countries and UN agencies to counter rising restrictions and pressures on Syrian refugees endangers their lives, compelling many to take perilous routes to Europe—resulting in the largest increase in migration there since the 2015 Mediterranean crisis. Concurrently, recent reductions in UN aid and food assistance further drive refugees to contemplate these risky journeys. Further cuts on the horizon will push Syrian refugees deeper into poverty and force aid agencies to cut their services to the most vulnerable.

Host countries should immediately cease refouling Syrian refugees and expand pathways for them to remain legally in neighboring countries. In return for this commitment, donors should offer host-countries a new package of support to fund local integration and dramatically expanded resettlement. To this end, the United States and EU could also work with host countries on more novel solutions, including expanding the donor pool to incorporate BRICS+ and GCC countries and capitalizing on initiatives like the Jordan Compact and the India-Middle East-EU Corridor to bolster the economic inclusion of Syrian refugees. Moreover, these steps should go hand in hand with broader U.S. and EU commitments to resettlement. Specifically, the Biden administration should aim to resettle at least 20,000 Syrian refugees by 2024.

If Syrian refugees face a choice only between forced return to an unsafe Syria or indefinite legal limbo and increasing destitution in neighboring host countries, many are likely to vote with their feet and attempt irregular migration to Europe and other places where they might find a better future.

Recommendations

To the Governments of Türkiye, Lebanon, and Jordan:

- Refrain from normalizing or enhancing coordination with the Syrian government on return of Syrian refugees. The Syrian government’s violence against civilians continues to fuel insecurity in Syria, including violence routinely directed toward Syrian returnees and deportees. Host-countries should challenge false narratives about improved security in Syria and avoid actions that rehabilitate the Syrian government and prolong the refugee crisis.

- Comply with international law and avoid pushing Syrian refugees to return prematurely or adopting policies that exert undue pressure on them. Host governments, especially Türkiye and Lebanon, should refrain from rhetoric that scapegoats Syrian refugees for local economic, social, and political challenges. Such behavior exacerbates tensions between refugees and host communities, heightening security risks for refugees. To mitigate this, host governments should counter disinformation and dispel myths about Syrian refugees through public advocacy campaigns.

- Respect the legal status of Syrian refugees residing in their territory and establish clearer pathways for them to remain without fear of deportation. This includes granting prima facie refugee status to those already in host countries and streamlining existing pathways, such as Türkiye’s temporary protection regime for registration, residency, and work permits. Properly implemented, these initiatives must grant refugees unfettered access to education, health, employment, and legal services, enabling them to reside without the constant fear of deportation.

- Immediately cease raids, detention, and deportation of refugees and strictly adhere to international non-refoulement obligations. This includes providing UNHCR permanent access to detainees or those flagged for deportation to ensure states are upholding and respecting refugees’ rights.

- Empower Syrian NGOs to help address the needs of refugees in host countries and in Northwest Syria. This includes easing NGO registration restrictions, permitting the hiring of Syrian NGO staff, and ending crackdowns on Syrian NGOs supporting humanitarian operations. Specifically, Türkiye should reduce pressure on Syrian NGOs supporting cross-border aid into Northwest Syria.

To the United States, European Union Members, and Other Donor Countries:

- Launch a Syria Refugee Study Group, comprised of U.S. government representatives, donor representatives, refugee leaders, scholars, and other key stakeholders to explore new opportunities for innovative solutions and make recommendations for supporting refugees and host countries.

- Pressure host governments to cease the persecution, raid, arrest, and refoulement of Syrian refugees. This includes utilizing all forms of leverage to push states to respect the rights of Syrian refugees, including those without proper legal identification, and end pressure on refugees to return to Syria. The United States and EU should condemn these actions (and put pressure on UN agencies to do the same), and use leverage, including security assistance, to ensure respect for refugee rights.

- Reiterate that Syria is not safe for return and challenge narratives that suggest otherwise. The EU should reject concerted actions by Cyprus to recognize certain areas as safe for return. Such steps contradict UN statements about insecurity in Syria and propagate a false narrative of security, which is detrimental to those who could be coerced to return.

- Implement a new aid package for host countries, incorporating non-traditional donors. This includes engaging BRICS+ and GCC nations to diversify and augment humanitarian and economic aid, reinforcing the collective commitment to the Syrian Refugee Response. Any direct financial support should be given in exchange for host governments’ commitments against refoulement.

- Expand resettlement of Syrian refugees. The United States and EU should expand refugee resettlement from Türkiye, Lebanon, and Jordan. The Biden administration should commit to accelerating the resettlement of at least 20,000 Syrian refugees by 2024 in exchange for host-state commitments against refoulement. This provides refugees alternatives to dangerous boat journeys to Europe and signals a commitment to responsibility-sharing.

- Use new support to promote refugee economic inclusion in host countries. The Unites States and EU should work with non-traditional donors to explore initiatives like the Jordan Compact or the new India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor as avenues to incorporate refugees into emerging economic opportunities.

To the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR):

- Reinforce refugee protection and condemn host countries’ violations of non-refoulement. The UNHCR High Commissioner and UNHCR country offices should advocate louder against efforts by host governments, especially Türkiye and Lebanon, to deport Syrian refugees. They must also demand access to those who have been detained or flagged for deportation.

- Strengthen protection monitoring for Syrian returnees and deportees. UN agencies, especially in Damascus, should intensify efforts to safeguard returnees. UNHCR in particular must press the Syrian government for access to monitor the safety of returnees throughout Syria and advocate for the release of those detained or missing. Concurrently, UNHCR offices in adjacent countries should collaborate with Syrian NGOs, who are already observing returnee conditions, to optimize access strategies and reporting methods.

Methodology and Research Overview

Refugees International conducted three research trips in Jordan, Lebanon, and Türkiye in June and July 2023 to assess the conditions and challenges facing Syrian refugees living in neighboring countries and evaluate the impact of recent steps between the Arab states to normalize relationships with the Syrian government on the viability of durable solutions for Syrian refugees. The team interviewed Syrian refugees, Syrian-led organizations, INGOs, UN officials, government officials, and an array of other experts in each country. This research builds on several years of research and interviews undertaken by Refugees International on the mounting challenges facing displaced Syrians both inside Syria and in neighboring Türkiye, Jordan, and Lebanon.

Background

Since May 2023, some diplomatic efforts to normalize relations with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad have intensified. After years of international political isolation, a push by Assad’s long-standing allies, chiefly Russia and Iran, and fatigue by its neighbors has opened the way for legitimization of the Syrian regime. The most significant momentum has come from countries in the region, notably demonstrated in May 2023 when the Syrian government was welcomed back to the Arab League. One major pillar of this effort aims to recast Syria as safe for Syrian refugees to return. This rhetoric has been welcomed by Syria’s neighbors who have been emboldened to push harder for Syrian refugees to go back prematurely. This dangerous trend poses dire risks for millions of refugees in Türkiye, Lebanon, and Jordan. This report lays out the main challenges in each country then highlights key aspects of this troubling trend, ending with recommendations for how it can be reversed.

*Syrian refugees registered with UNHCR as of October 2023

Türkiye

Conditions for Syrian refugees residing in Türkiye have noticeably worsened since Refugees International visited Türkiye in May 2023 following a post-earthquake wave of anti-Syrian policies and political rhetoric. The February 4 earthquakes, which struck Southeast Türkiye and Northwest Syria, left tens of thousands of Syrians and Turks dead and hundreds of thousands displaced and homeless amid widespread destruction of buildings and critical infrastructure. The earthquake amplified the suffering of millions of Syrian refugees in heavily impacted areas.

Türkiye hosts as many as 3.6 million Syrian refugees, who hold temporary protection (TP) status within Türkiye. However, it is becoming increasingly uncertain whether this status will be sufficient to remain in Türkiye. As Ankara weighs its future role in Syria, senior Turkish officials have met with their Syrian government counterparts in discussions, brokered by Russia, around a pathway to normalization. President Erdoğan, empowered by his May 2023 election victory, has promised to return 1 million Syrians to Northwest Syria. Shortly after, Turkish authorities began a major crackdownon Syrian refugees in many Turkish provinces, notably Istanbul, of those residing and working without proper legal permits. Syrian refugees, while still reeling from the physical, emotional, and psychological toll of the earthquake, now face threats of arrest, detention, and deportation by Turkish authorities. Deportations, while not necessarily new to Türkiye, have increased in rate, resulting in the deportation of as many as 20,000 Syrians in 2023. The number could be higher. See section “Raids and Refoulement.”

Lebanon

Conditions for Syrian refugees in Lebanon have worsened considerably over the past year. Lebanon is the country with the highest refugees per capita globally with an estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees—or a quarter of Lebanon’s population. Most Syrian refugees in Lebanon lack basic access to humanitarian aid, with nearly half of Syrian children out of school. Most Syrians lack legal work permits, pushing them into the precarious informal sector, and heightening their risk of exploitation. The repercussions of the nation’s deteriorating economic and political situation, intensified by the Beirut explosion in 2020, have thrust over 90 percent of these refugees into acute poverty.

Lebanon faces one of the region’s most severe economic downturns, resulting in soaring inflation, widespread job losses, and reduced access to essential goods and services. These conditions are intensifying the humanitarian plight of both Syrian refugees and Lebanese citizens, with both groups sinking into poverty with limited prospects for relief. As Lebanon’s economic and political infrastructure deteriorates because of corruption and economic mismanagement, state institutions have largely deteriorated, leaving major gaps in services to support affected communities. Instead of addressing these challenges, some political elites deflect responsibility by scapegoating Syrian refugees, escalating tensions within host communities and fueling public backing for harsher measures against refugees, including detention and deportation.

Jordan

Jordan hosts more than 1.2 million Syrian refugees, with 680,000 registered by UNHCR. Most live within Jordanian communities, while about 10 percent reside in the Zaatari and Azraq refugee camps. Jordan offers enhanced employment opportunities for these refugees in exchange for favorable EU trade access under the Jordan Compact. Yet, many Syrians still work in low-wage informal sectors or depend on UN assistance.

Most refugees in Jordan fled Southwest Syria, which was retaken by Syrian forces in 2018. The region’s ongoing instability has lessened their hopes of returning. While Jordan aims to enhance conditions in areas of return and curb narcotics trafficking along its borders, it believes reconciliation with the Syrian government is essential to achieve these goals.

Jordan leads in advocating for Syria’s Arab League reintegration and broader global diplomatic acceptance. Concerned about dwindling donor support, Jordan and Türkiye emphasize the importance of engaging with the Syrian government to facilitate refugee returns. This stance risks using the refugee populace as leverage in negotiations, potentially enabling countries like Lebanon to adopt stricter measures against Syrians.

The Push for Return

Türkiye, Lebanon, and Jordan see the return of Syrian refugees as a preferred near-term objective. In theory, voluntary repatriation is best suited if conditions allow for returnees to undertake a safe, voluntary, and dignified return. The protracted nature of the refugee crisis, however, is pushing governments to jumpstart the process of return even without any such safeguards in place. Those familiar with recent efforts by senior UN and Arab officials to engage with the Syrian government told Refugees International that the Syrian government, emboldened by recent normalization gains, will not provide sufficient protection guarantees or access for UN monitors to ensure the safety of returnees. The eagerness of Arab governments to normalize diplomatic relations with the Assad regime thereby works at cross-purposes to their objective of repatriating refugees. Even if such safeguards were agreed to, there is little evidence the Syrian government would abide by them. Indeed, new reports are emerging of the detention, torture, and disappearance of returnees in recent months. These reports underscore the regime’s intransigence on the question of safe and dignified returns.

Nevertheless, in May 2023, Jordan jumpstarted negotiations between Arab states and the Syrian regime on the repatriation of Syrian refugees. Jordan’s pilot plan calls for the return of at least 1,000 Syrian refugees in exchange for donor commitments to funding for early recovery in areas of return. Officials offered no timeline for the plan, but argued that it could “serve as a model that would establish and encourage a comprehensive plan for the voluntary return of refugees.” This proposal was endorsed by Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Egypt. But UN officials and one donor told Refugees International that the proposal has not gained traction with UNHCR or Western donors. This initiative by Jordan is only the latest in a series of regional efforts, including those by Lebanon and Türkiye, to repatriate Syrians. Previous efforts have all failed to facilitate the safe return of Syrian refugees. One interlocutor told Refugees International staff that Jordan’s current push for return may have indirectly emboldened more forceful deportations by Lebanon.

Politicizing Refugee Return

Jordan has been actively engaged in discussions with the Syrian government as well as senior UN officials to solicit progress on its repatriation proposal. Interlocutors familiar with these negotiations told the Refugees International team that Jordan has struggled to secure favorable guarantees from the Syrian government for the necessary safeguards for returnees, such as protections against conscription, arbitrary detention arrest, torture, and forced disappearance (among others).

There was a broad consensus among UN agencies, donors, and INGO officials the Refugees International team interviewed that the Syrian government fundamentally does not want Syrians to return, except for a small number that can bolster the regime’s political legitimacy. One Syrian NGO staff told Refugees International that the Syrian government “…employs the refugee card as a bargaining chip for pressuring neighboring countries to engage in normalization and reconstruction.” A senior European official told Refugees International that “normalization has been emboldening [regime] intransigence.” This is complicated further by the Syrian government’s tight controls over the humanitarian environment inside of Syria and its long history of controlling both the access and the actions of UN agencies and INGOs in Damascus.

Jordan will likely continue to press UN agencies, donors, and the Syrian government for a timeline to send Syrians back. Any such agreement is premature unless the legitimate protection needs of returnees are guaranteed, in addition to a clear reduction in fighting and improvement in the availability of basic services in areas of return. Donors should underscore this position and signal to both neighboring countries, particularly Jordan, and the Syrian government that it will not bankroll unsafe returns in any form.

No Monitoring Mechanisms for Returnees

UNHCR is largely unaware of returnees’ or deportees’ conditions because they lack a robust returnee monitoring system in Syria and neighboring countries. This data is critical to ensure that UNHCR can intervene when returnees’ rights are compromised.

Most humanitarian workers Refugees International interviewed noted protection monitoring must be a precondition before major returns can occur. Yet, no standardized mechanisms exist. UNHCR stressed to the Refugees International team that Syria remains unsafe for refugee return, and they are careful not to endorse or promote returns because “…there is no evidence conditions in Syria are conducive for return.

However, this careful approach has created a tension between UNHCR’s mandate to oversee returns and its reluctance to potentially encourage premature returns. Tens of thousands of Syrians have returned since 2017, but UNHCR has faced difficulties monitoring these returns. A UN official told the Refugees International team that UNHCR in Syria depends on indirect sources, mainly government-affiliated partners, to gather fragmented data on returnees. The Syrian government does not allow UNHCR to expand this access, particularly in southwest Syria, where most Syrian refugees in Jordan originated. Some INGOs and Syrian NGOs have tried informal monitoring, but these attempts are not a replacement for a UN returnee monitoring mechanism.

Concerns loom over the targeting of returnees and deportees by Syrian authorities, including reports of torture, extortion, and forced disappearance. The silence from UNHCR in Damascus is alarming. A high-ranking official from a Western government told Refugees International that UNHCR Syria is not sufficiently pressing the Syrian government for access to returnees. Meanwhile, UNHCR offices in neighboring countries have tried informal monitoring, but face major impediments in accessing and assessing potential returnees and deportees.

Donors and UNHCR in Geneva must put more pressure on UNHCR Syria to fulfill its mandate to monitor the safety and conditions of returnees. Soliciting Syrian government cooperation, however, remains a major impediment. In the absence of government cooperation, donors should coordinate with UNHCR offices in neighboring countries as well as neighboring countries (whose border authorities often document Syrian returnees) to expand information sharing on returnees. Donors should also coordinate with Syrian NGOs who are currently implementing informal returnee monitoring through their robust networks with Syrian communities.

Worsening Environment for Syrian Refugees

The failure to secure voluntary returns at scale is driving a more repressive approach to Syrian refugees and eroding conditions for refugees in Türkiye, Lebanon, and Jordan. A series of challenges now threaten refugee protection and heighten the vulnerability of refugees in Türkiye, Lebanon, and Jordan. In Lebanon and Türkiye, many Syrian refugees cannot obtain the legal documents necessary to remain. Those who lack legal status face severe restrictions in their daily lives, including in mobility, access to jobs, and basic services. Host governments continue to worsen these conditions by proliferating anti-refugee rhetoric, fomenting deeper resentment among host communities, and scapegoating refugees for a range of international problems. Meanwhile in Jordan, deep cuts in UN aid are being felt among Syrian refugees, especially for those in camps who are entirely reliant on the UN and donors for funding.

Post-earthquake Challenges in Türkiye

In Türkiye, the February 2023 earthquakes and a tumultuous election later in May accelerated the deterioration of conditions for Syrian refugees. Syrian refugees face strong xenophobic and anti-refugee propaganda in their communities following the earthquake, driven largely by escalating political rhetoric in the run-up to the May presidential election.Politicians have scapegoated Syrians for various national issues, including economic instability and inflation. Such rhetoric has permeated host communities, stirring resentment further inflamed by the earthquake aftermath. A Syrian NGO worker conveyed to Refugees International that the earthquake eroded social ties between refugees and Turkish citizens and heightened tensions, which occasionally manifested in targeted violence, such as the tragic murder of a Syrian refugee in the border town of Reyhanli.

While both Turkish citizens and Syrian refugees were equally affected by the catastrophe, Syrian refugees expressed to Refugees International that their Turkish neighbors saw them as competition for aid and services. One Syrian aid worker explained that while the Turkish government did not neglect Syrian refugees, it did prioritize Turkish citizens who often received better accommodations and assistance.

Post-election, these anti-Syrian sentiments persisted. Many Syrians hoped Erdoğan’s election would curtail the political vilification of refugees and reduce pressure on them. However, more aggressive interactions between Turkish authorities and Syrians following the elections, including raids and detention, diminished these hopes. One Syrian refugee told Refugees International, “They [Türkiye] are giving signs that we [Syrians] are no longer welcome.”

Beyond the quake’s devastation, the economy’s downturn and the depreciating Turkish Lira have forced Syrian refugees further into poverty. Syrian NGOs reported to Refugees International that these conditions have increased the rates of child labor. They also noted that a significant number of Syrians sought better informal employment opportunities in bigger cities, notably Istanbul, after the earthquake destroyed sources of livelihood in disaster areas. Yet, this post-earthquake migration poses new risks. Those in the informal sector, often underpaid and without insurance, are concentrated in areas frequently targeted by Turkish security raids.

Many of the roughly 1.7 million Syrian refugees spread across eleven provinces impacted by the earthquake relocated within the country. Typically, Syrian refugees with TP or international protection status cannot move outside their registered province without municipal travel permits. However, this rule was temporarily relaxed post-earthquake until October 27, specifically for those from the six most quake-affected provinces. This has led many Syrians to relocate elsewhere. While some utilized the temporary relocation period to temporarily return to Northwest Syria, intending to re-enter Türkiye within the stipulated period, others remained, taking refuge in temporary shelters ranging from informal camps to official centers. Many other yet migrated to key urban hubs, especially Istanbul.

Türkiye’s relaxed travel permissions for Syrians, initially designed to temporarily allow Syrians from earthquake areas to travel to Syria and return within a stipulated time, was inadequately rolled out. This led to significant confusion regarding the eligibility criteria for Syrian refugees. NGO staff informed Refugees International that the initial introduction of the scheme failed to clearly define which Syrian refugees could relocate.

As a result, many ineligible Syrians moved to different regions, notably Istanbul, putting them at grave risk if intercepted by Turkish authorities without the appropriate travel permits. NGO officials told Refugees International that such refugees could be detained and deported if caught. In the past, Syrians found outside their registered province without permission were returned to their respective provinces. However, based on current trends, Turkish authorities are increasingly deporting Syrian refugees from detention centers directly to Northwest Syria, bypassing their respective provinces.

Additionally, Syrian refugees and humanitarian personnel reported to Refugees International that Turkish authorities barred re-entry for a smaller group of Syrian refugees who ventured to Syria during the travel grace period. While Refugees International staff were not able to directly corroborate the reasons these groups were denied entry, one UN official said the cases were the result of the policy’s lack of clarity, which created confusion for some Syrians over who could benefit from the relaxed travel restrictions.

The temporary relocatIon permission is not a long-term fix for Syrian refugees displaced by the earthquake. Their future in areas of relocation remains ambiguous. The Turkish Presidency of Migration Management, which oversees Türkiye’s refugee policies, has not yet provided further guidelines for when the permit expires this month. As a first step, Turkish officials should extend the grace period beyond October, and streamline the process for Syrian refugees to regularize their new province of residence. This current limbo hinders Syrians from permanently settling, as their travel permissions remain volatile.

Lebanon Closes the Door on Legal Registration

Conditions for Syrian refugees in Lebanon have been in decline for several years, but a worrying series of changes in the legal space are threatening the security of Syrian refugees. In 2022, Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Miqati urged the global community to “assist Lebanon in facilitating the return of displaced Syrians to their homeland.” Failing this, he warned that Lebanon would remove Syrian refugees “by legal means.” Since then, Lebanese authorities have capitalized on the ambiguity of the nation’s poor immigration laws to magnify the legal uncertainties facing Syrian refugees, expedite their return, and, where possible, directly deport them. The persistent instability of Lebanon’s political landscape exacerbates this situation, perpetuating the legal limbo for Syrian refugees.

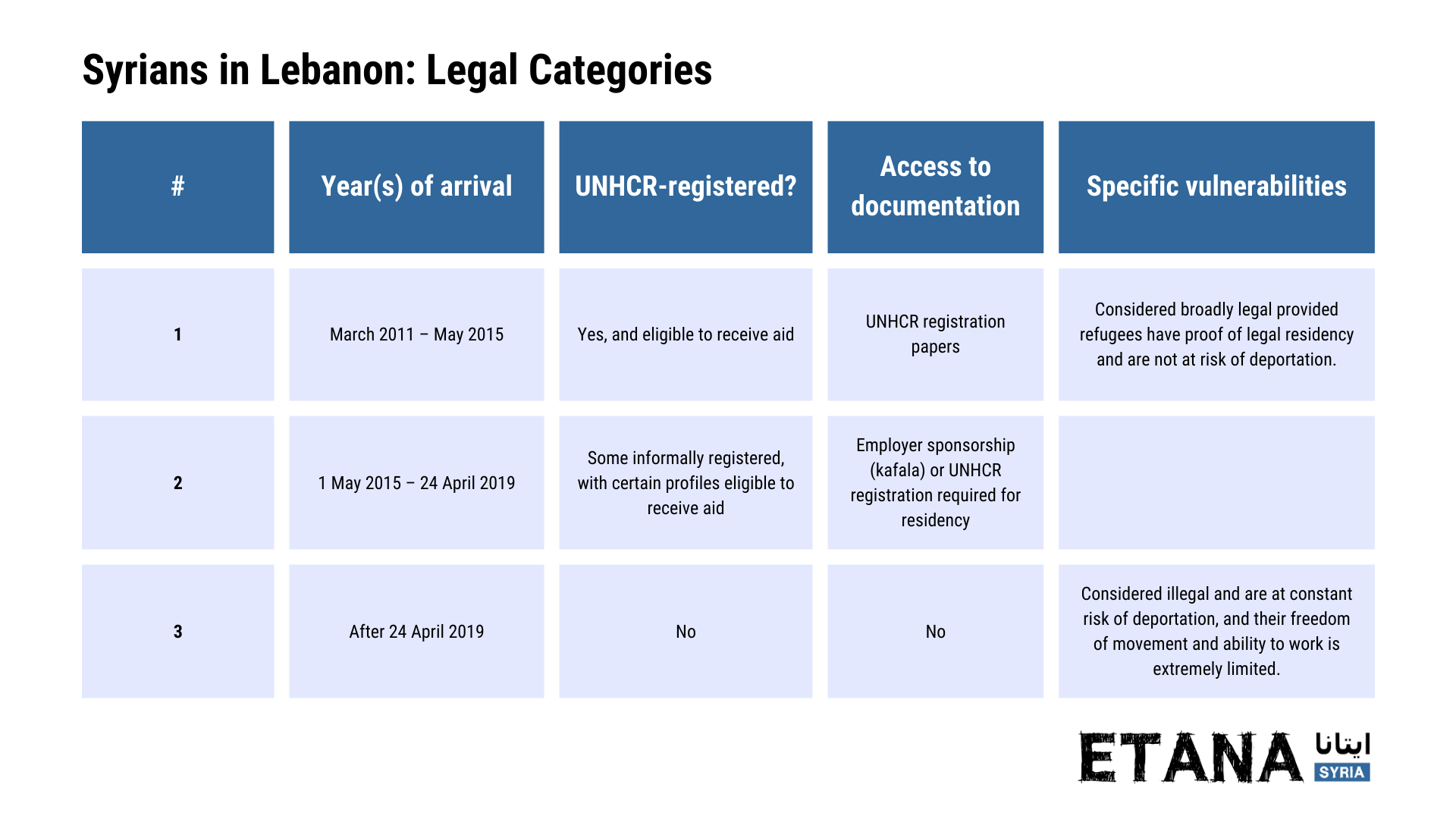

Before 2015, Syrians could enter Lebanon without a visa and register for refugee status with UNHCR. This changed in 2015 when Lebanon forced UNHCR to stop new registrations in a bid to restrict the inflow of refugees. Instead, UNHCR provided Syrians arriving after 2015 with a QR code indicating their humanitarian need, which does not grant official refugee status or provide any legal protections.

Syrians who arrived after 2015, or those without valid residency, face potential deportation by Lebanon’s General Security Office (GSO). While this process poses legal and ethical concerns, it offers a degree of due process, allowing bodies like UNHCR to contest GSO-ordered deportations. However, in 2019, the Lebanese Higher Defense Council (HDC) decreed that anyone entering unofficially after April 2019 would be expelled, sidestepping what due process the GSO offered and reversing previous assurances by Lebanese authorities they would not deport refugees. This HDC directive offers no avenue to challenge deportation orders, enabling indiscriminate deportations without regard to humanitarian concerns. See section“”Raids and Refoulement” for more on deportations.

The process of obtaining legal status is arduous for Syrian refugees, with only 17 percent of Syrians possessing valid residency due to Lebanon’s stringent immigration rules. Consequently, about 1.24 million Syrians are without legal status. As a result, most Syrian refugees lack the necessary legal recognition to safeguard them from detention, forced removal, and deportation.

On May 15, 2023, the GSO issued a decision that curtailed Syrian refugees’ chances of regularizing their status in Lebanon, closing the door for most Syrians to obtain legal status. The ruling restricts Syrian refugees who entered Lebanon irregularly before April 2019 from obtaining legal status under Lebanese law. This places a significant number of Syrian refugees, even those registered with UNHCR, at heightened risk of refoulement. Now, to gain official status, Syrian refugees must voluntarily depart for Syria, pay a number of fees, and then re-enter Lebanon. This not only imposes undo financial strain but also poses substantial risks by potentially forcing them to temporarily return to Syria and face arrest or worse.

Also in May 2033, several Lebanese municipalities implemented discriminatory regulations – refugee curfews, restraints on freedom of movement, and housing restrictions – in response to the May 2 circular (no. 42) from the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities (MoIM). This circular requires Syrian refugees to register with their local municipality or else face prohibitions on renting housing and obtaining civic documents like wedding and birth certificates. Additionally, according to local human rights monitors, certain municipalities are demanding that Syrians provide personal documents and proof of residence, using the threat of deportation as leverage for compliance.

Less Aid, Less Inclusion in Jordan

Jordan perceives Syrian refugees’ stay as provisional and ties their support directly to ongoing donor contributions for the refugee response. This poses major challenges with large-scale cuts in U.S. and UN assistance on the horizon. The topic of refugee integration locally stirs contention due to the fear that the Syrian refugee population in Jordan may be permanent. Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi, in an August 23 meeting with UNHCR High Commissioner Filippo Grandi, stressed that “the future of Syrian refugees is in their own country, not in Jordan.” King Abdullah II echoed this sentiment at the UN General Assembly in September 2023. Despite this view, Jordan’s leaders begrudgingly acknowledge that refugees are unlikely to go back to Syria. This, coupled with concerns over the future of donor support, has reduced Jordan’s cooperation with UN agencies and INGOs on refugee inclusion initiatives.

The loss of donor funding could reverse previous gains to refugee inclusion, including Jordan’s willingness to provide refugees access to healthcare, education, and other services. Some donors are pursuing other forms of direct sector support to sustain refugee access. For example, Germany announced an EU22.4 million grant to fund the salaries of teachers teaching Syrian refugees. This form of direct provision may be one near-term option to improve refugee inclusion. Other avenues include factoring Syrian refugees into bilateral funding mechanisms, such as the U.S.-Jordan Memorandum of Understanding, which provides Jordan with $1.4 billion in annual assistance. See section “Recommitting to the Syrian Refugee Response” for more.

Raids and Refoulement

Thousands of Syrian refugees have been forcibly deported from neighboring countries to Syria in the first half of 2023. This alarming trend is fueled by the misleading narrative, championed by Russia and some members of the international community, that Syria is now safe for returnees. Seizing on this narrative, host governments have exerted undue pressure on Syrians to return.

Türkiye

Turkish authorities have increased systematic raids, detention, and deportations of Syrian refugees, as reported to Refugees International by NGO and UN officials. This intensification coincides with a period of heightened uncertainty for Syrian refugees, exacerbated by the recent earthquake and growing demands for their repatriation. Although these raids began as early as January 2023, the frequency and intensity have markedly increased. Syrian refugees are being detained and transported to processing centers before being forcibly returned to Syria. According to estimates provided to Refugees International by UN and NGO representatives, as many as 20,000 Syrians have been deported since January 2023.

The intensified raids have generated fear within Syrianommunityies, particularly due to the indiscriminate nature of these deportations and the inclusion of those holding temporary protected status. Syrian refugees informed Refugees International that the “Temporary Protection” status offered little respite from potential harassment or deportation by Turkish authorities. One Syrian refugee voiced their concerns to Refugees International, stating, “Syrian refugees need clear [legal] procedures. Temporary Protection is not clear, and there is no guarantee it will protect you.” Even if Syrians can evade deportation, in some instances, minor disagreements or misunderstandings with Turkish authorities have led to the revocation of Syrians’ temporary protection status. While legal services are available through INGOs and UNHCR for those taken by Turkish authorities, most are largely unaware of how to access them, especially once in detention.

Turkish authorities maintain that the returns they facilitate are voluntary. However, credible reports from NGOs, rights monitors, and UN agencies contest this narrative. A UN official highlighted to Refugees International that UNHCR is granted access only to a limited number of cases receiving legal assistance, leaving them uninformed about the larger cohort of detained or deported individuals. Another official told the Refugees International team that Turkish authorities have resorted to threats of prolonged detention to pressure detainees into signing “voluntary” repatriation documents under duress. Reports shared with Refugees International also mentioned instances of physical abuse against refugees in detention facilities, consistent with documented incidents from 2022. Turkish authorities should allow UNHCR access to detention and processing centers, as well as border crossings to assess return conditions or identify specific protection requirements of those detained and flagged for deportation.

Lebanon

From April to May 2023, the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) launched a concentrated campaign of extensive raids and detentions aimed at Syrian refugees who lack legal residency. According to the UN and various NGO officials, the LAF actions were premised on the aforementioned HDC’s 2019 mandate, which offers no due process for those apprehended.

NGO sources informed Refugees International that LAF operations targeted areas with known high concentrations of Syrian refugees, utilizing tactics like random checkpoints and raids on housing blocs known to house Syrians. Those detained who could not produce residency permits on the spot faced immediate detention and subsequent deportation. Syrian activists told Refugees International that some deportees were handed directly to the Syrian army’s notorious Fourth Division, known for its atrocities against civilians during the war, while others were simply left stranded at the border. Those taken by Syrian authorities underwent abuse and torture in Syrian military custody according to activists and NGOs familiar with the operations. In one case reported by Human Rights Watch, a deportee was arrested and tortured by Syrian military intelligence at the infamous “Palestinian Branch” along with 12 other deportees. Similar reports of abuse were also documented by the UN Syria Commission in their report to the UN General Assembly.

By May 11, due to international pressure, the LAF reduced the scale of its operations, though isolated deportations continued, especially in the northern regions. The total number of refugees detained and deported remains undisclosed by the Lebanese Government. NGO estimates range from 500 to 2,000 deportations. Such actions, particularly refoulement, are in clear breach of human rights and international law.

The operations are traumatizing the Syrian community in Lebanon. UNHCR has observed heightened psychological distress among many affected Syrian refugees. Fearful of potential arrests, many are policing their movements, opting to stay home. Syrian refugees in border regions, where pushbacks are commonly reported, avoid traveling to UNHCR offices altogether due to concerns they might be intercepted and deported by Lebanese officials at checkpoints along the route. Simultaneously, some Syrian NGO leaders advised their teams during the most intense raids to remain indoors to evade possible targeting. This self-imposed isolation sometimes lasted over a month for some and froze some NGO-led operations until it was deemed safe for Syrian staff to return to the office.

Lebanon’s general security office (GSO) relaunched a pre-COVID program to facilitate the voluntary repatriation of Syrian refugees willing to go back, separate from the LAF deportations. Two facilitated returns in late 2022 saw approximately 700 individuals move back to Syria. These returns are relatively infrequent. However, more are expected in the future.

A UN official told Refugees International that UNHCR has a limited ability to oversee returnees due to restrictions set by the Lebanese government on border access. They can only monitor returns facilitated by the GSO, like the ones in 2022. Even this access is granted last minute, in some cases with only a single day’s notice, an insufficient window to assess conditions for hundreds of refugees at a time. UNHCR has also had no access to those detained by the LAF in the raids in May. NGOs expressed dissatisfaction with UNHCR’s muted response during these deportations, especially given their limitations to advocate, fearing potential government retaliation.

Jordan

Despite Jordan’s aforementioned coordination with the Syrian government for a timeline to return Syrians, the Kingdom has largely refrained from the widespread deportation of refugees to Syria, unlike Türkiye and Lebanon. Jordan has been accused of smaller-scale deportations in the past, particularly in cases where a refugee is perceived to be a direct threat or affiliated with terrorist actors. In these cases, Syrian refugees continue to be sent to Rukban, a desert displacement camp in eastern Syria. Meanwhile, other humanitarian personnel told Refugees International staff that some Syrian refugees who are apprehended by Jordanian authorities for a range of reasons from informal work to misdemeanors are sent to refugee camps where they face restrictions to their freedom of movement.

Closing Humanitarian Space

Syrian refugees have long played a leading role in humanitarian response both in neighboring countries and in Northwest Syria. However, harsher refugee policies targeting Syrians across the region are shrinking this humanitarian space and putting Syrian NGOs and their staff at dire risk of harassment, retaliation, or, in the worst case, deportation to Syria.

Türkiye

In Türkiye, the crackdown on Syrian refugees in Istanbul has significantly affected Syrian-led NGOs. Every Syrian NGO worker interviewed by Refugees International conveyed heightened concerns regarding both their legal status and that of their colleagues. One individual highlighted that due to bureaucratic obstacles and legal intricacies, most Syrians working for NGOs in Gaziantep do not possess proper work permits. Several NGO workers told Refugees International that state regulations stipulate that organizations must hire a certain quota of Turkish citizens for every Syrian they employ.

Some Syrian refugees have resorted to informal employment within the humanitarian sector. This, however, places greater risk on Syrian NGOs. One NGO officer expressed apprehension about potential raids on NGOs by local authorities. Other humanitarian personnel told the Refugees International team that Syrians working informally are likely to be deported if detained in raids. They also expressed that legally registered Syrians employing other refugees without work permits are also at risk of detention, and, in some cases, deportation. Many Syrian employees have chosen to work remotely to minimize the risk of unwarranted confrontations.

There are few avenues for addressing these concerns. NGOs risk repercussions if they openly criticize the government’s mistreatment of Syrian refugees, including potential reprisals from state security. As one Syrian NGO worker told Refugees International, “Effective advocacy is occurring outside of Türkiye, because doing anything inside Türkiye perceived as a threat would expose them [Syrian refugees] to losing their legal status.” Therefore, Syrian NGOs, many of which spearhead humanitarian efforts in both Türkiye and Northwest Syria, find themselves in the challenging position of balancing their contributions to the cross-border response in Northwest Syria with the safety of their staff. As articulated by a senior NGO member, “the risks of speaking out outweigh the desire to act.” Turkish authorities, who rely on Syrian NGOs to support the cross-border aid effort, need to drastically scale back pressure on NGOs or risk undermining their role in maintaining the fragile aid environment in Northwest Syria.

Lebanon

Syrian NGOs, along with INGOs, are often the sole providers of essential services like health and education to both Syrian refugees and Lebanese communities. However, Lebanon’s tightening refugee policies are squeezing the humanitarian ecosystem, particularly impacting Syrian-led NGOs. This squeeze results from a convergence of more rigid legal restrictions for Syrian refugees, increasing state pressures on NGOs, and waning donor support, all of which undermine the efficacy of refugee-led organizations operating in Lebanon’s remote regions.

Adding complexity, the Lebanese government’s intensified oversight of humanitarian activities is influencing donor decisions. Authorities now require NGOs and donors to employ either Lebanese nationals or Syrians with valid work permits. NGOs told the Refugees International team that most major donors have complied, specifying that NGOs employ only Syrians with valid permits. This compliance inadvertently disadvantages Syrian refugees, as legal work permits are challenging for them to secure. Instead, employment tends to favor Lebanese nationals. One NGO representative disclosed a compromise they made with a primary donor: while they protected current Syrian employees, they agreed not to recruit additional Syrians. This compromise, they emphasized to Refugees International, effectively creates a bias against hiring Syrians. Still, a few NGOs continue to employ Syrian refugees lacking the required permits, although they recognize the potential risks if targeted by Lebanese authorities.

Furthermore, Syrian NGOs conveyed to Refugees International their apprehensions about speaking against the raids and deportations by the Lebanese Armed Forces. They fear governmental backlash that could jeopardize their Syrian staff. One organization that openly opposed these policies reported to the Refugees International team that they experienced harassment by state authorities.

Jordan

Unlike Türkiye and Lebanon, Jordan hindered the growth of Syrian civil society by barring Syrian NGOs from operating. This has limited Syrian refugees’ participation in aid initiatives and influenced policies affecting them. The resulting communication gap between refugees and UN agencies has deepened Syrian refugees’ mistrust of them. Some Syrians even see recent waves of UN aid cuts as a tactic to force their return. A UN official told Refugees International that the lack of effective communication with refugee communities poses challenges in dispelling misconceptions, such as the notion that the UN is intentionally cutting aid to push Syrians out.

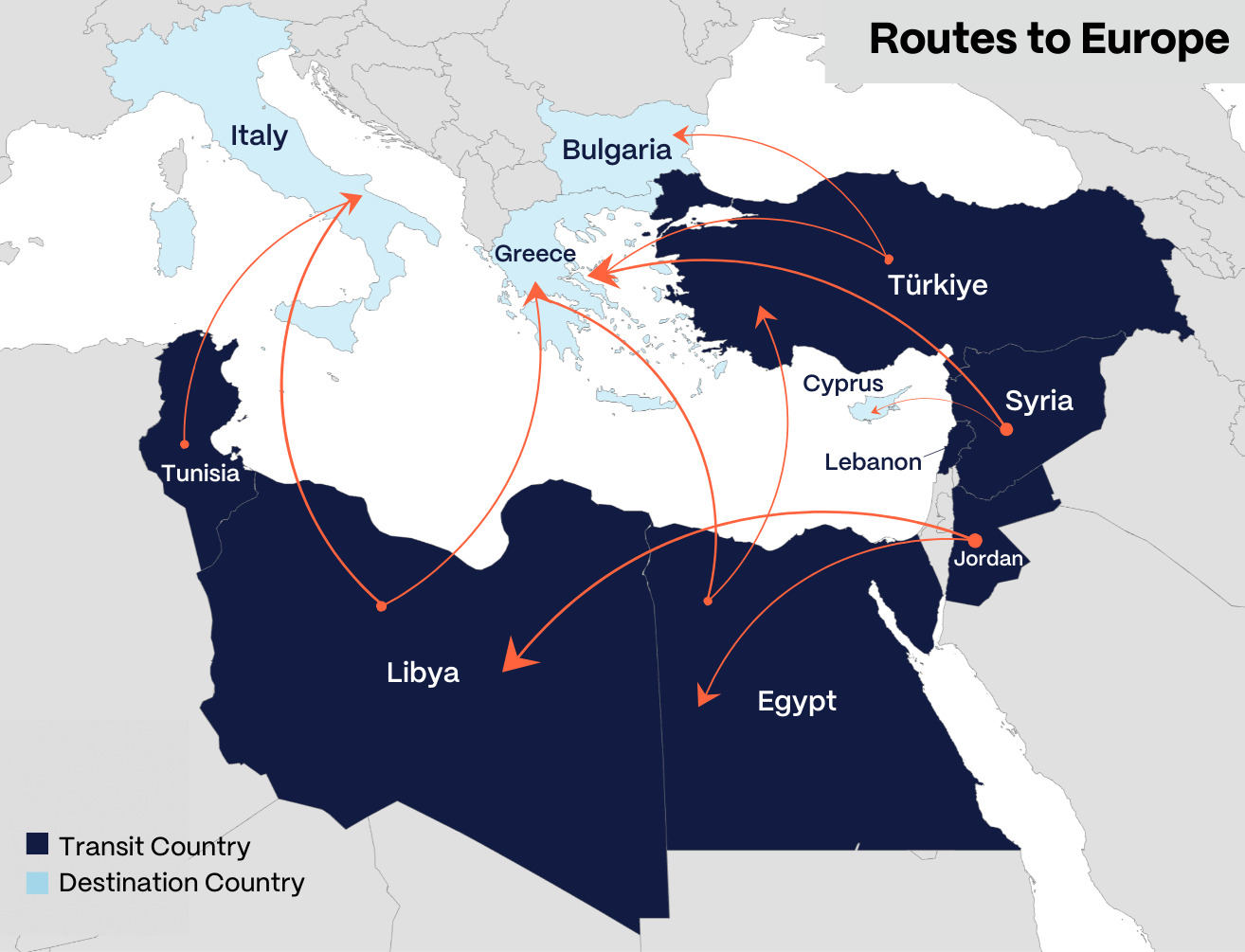

Fleeing to Europe

In 2023, roughly one in four Syrian refugees, up from 16 percent in 2022, considered relocating to Europe in search of a better life, according to UNHCR. This year also saw a marked rise in the number of Syrians seeking to travel to Europe through formal and informal channels. The first half of the year saw asylum applications in the EU surge, with 67,000 Syrians applying—the largest figure since the 2015-2016 refugee crisis. Syrians constituted 14 percent of all EU asylum applications during this period. Additionally, thousands have chosen to use dangerous land and sea routes to reach Europe. In 2023, EU reports indicate that more than 34,000 Syrians arrived via the Western Balkans by land, while around 6,000 ventured by sea via the eastern Mediterranean, primarily passing through Türkiye, Lebanon, and North Africa.

Lebanon, traditionally not a major transit country, is becoming a central point of departure for Syrians, Palestinians, and even Lebanese taking sea routes to Cyprus, Greece, and Italy. A UN official told the Refugees International team that 2022 saw a significant rise in Mediterranean crossings from Lebanon, mostly Syrians. In response, Lebanese authorities have cracked down on boats departing for Europe. UNHCR data shows around 75 percent of boats heading to Europe from Lebanon are intercepted or turned back. Syrian refugees who are intercepted by Lebanese authorities have been detained and deported to Syria upon return to shore, as witnessed in January 2023. Moreover, those who do manage to reach places like Cyprus are at risk of being deported back to Lebanon, and then subsequently deported again to Syria.

In light of rising numbers of boat arrivals via Lebanon, some EU members, notably Cyprus, are urging the EU to reconsider its policy against returning asylum seekers to Syria. They have suggested an EU-Lebanon agreement similar to the recent EU-Tunisia deal, which was aimed at curbing maritime movements to Italy. This proposition envisions compensating Lebanon to prevent boats with refugees from setting sail. However, such measures might prove ineffective as they overlook the root causes driving refugee movements from Lebanon: persistent instability in Syria, worsening conditions in Lebanon, and the narrowing legal avenues to Europe, especially resettlement. A better mechanism would be working with Lebanese authorities through increased financial support and UN humanitarian support to improve domestic conditions for Syrian refugees and poor Lebanese and Palestinian communities who are fleeing alongside Syrians.

Recommitting to the Syrian Refugee Response

The situation for Syrian refugees across the Middle East has since declined. This has had a cascading effect on refugees throughout the region. The way to reverse these trends, or even sustain a basic threshold of support to sustain neighboring host countries, is a mix of traditional and new approaches.

New Aid Package

In 2024, the Syrian humanitarian sector anticipates sharp aid reductions, with NGOs reporting to Refugees International that donors have notified them of large cuts in the next year. As international agencies, including the UN, cut back on food and cash assistance, the most vulnerable refugees stand to suffer the most. This pullback in funding not only puts strain on host nations, potentially leading to stricter measures and increased deportations, but also leaves refugees struggling for basic necessities. Such financial pressures may push refugees to return to Syria prematurely or migrate to Europe. It is vital for donors to reconsider these cutbacks and devise specific support packages for host countries.

Such packages should tackle escalating challenges faced by refugees and host communities and promote the sustainable integration of Syrian refugees. This can encompass programs that enhance access to employment, education, healthcare, and legal resources, fostering a welcoming environment for refugees. In Jordan, the United States could optimize its $1.45 billion annual Memorandum of Understanding to finance initiatives that prioritize refugee inclusion, like health, education, and job opportunities. Alongside existing strategies like the Jordan Compact, donors can also explore linking broader job market access for Syrian refugees to emerging regional development projects, especially the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor that spans Jordan.

In Lebanon, direct large-scale U.S. or EU support to the government should be considered only with safeguards in place to ensure aid reaches those target communities. Instead, they should expand support for UN agencies, INGOs, and Syrian NGOs, who serve as primary aid providers for Syrian and Lebanese communities. Donors should also push the Lebanese government to grant UNHCR the autonomy to execute its roles with minimal state intervention. Concurrently, the United States and EU should expand refugee support programs for Syrian refugees in Türkiye in exchange for Türkiye’s commitment to reduce pressure on refugees and increase operational space for Syrian NGOs to continue supporting the response in Northwest Syria.

Reviving Resettlement

The U.S. and EU’s meager resettlement quotas for Syrian refugees must also be expanded to enable legal pathways for more Syrians to reach safety – and to demonstrate better burden-sharing with frontline host countries. In 2023, the UNHCR projected 762,000 Syrian refugees from Jordan, Lebanon, and Türkiye urgently needed resettlement—marking a 22 percent surge from the previous year. Yet, the actual number of refugees resettled fell far short. Only 4.2 percent of the anticipated 610,000 from 2022 found new homes. Notably, during the first eight months of 2023, the United States has resettled a mere 3,881 Syrian refugees from the region, which is approximately 0.5 percent of the total projected need. Many fear that this number could decrease further as US resettlement priorities shift more to the Western Hemisphere. Indications from one UN official to Refugees International suggest some donors may discontinue Syrian resettlement initiatives in Lebanon for 2023-2024. To address this shortfall, the Biden administration should aim to resettle at least 20,000 Syrians in the United States annually.

Resettlement, though relatively modest in scale, plays a crucial dual role. It not only safeguards the most vulnerable from ongoing crises but also establishes a conducive environment for productive diplomatic interactions with host countries. This enhanced collaboration can pave the way for more inclusive refugee policies and initiatives, currently sidelined in many host nations’ agendas.

Energize Non-traditional Approaches

Donors should also explore innovative strategies, like launching a Syria Refugee Study Group comprising UN officials, donors, refugee leaders, scholars, and policymakers, to devise long-term solutions for the refugee crisis. Complementary pathways to resettlement, such as family reunification, private sponsorship, and employment visa schemes, should also be broadened to offer refugees swift relief from prolonged displacement. Concurrently, the United States and EU must engage non-traditional donors, including the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, BRICS+ nations like India and China, multilateral development banks, and other stakeholders in the Middle East, to augment humanitarian aid for Syrian refugees.

Conclusion

The Syrian refugee crisis in the region has reached its zenith. After over a decade of conflict, Türkiye, Lebanon, and Jordan are actively strengthening ties with the Syrian government and pushing Syrian refugees to return despite the grim realities in Syria. The Syrian government capitalizes on this situation, leveraging the crisis for political gains, even as Syrian refugees’ plight deepens. Host countries must commit to cease the refoulement of Syrian refugees, expand legal avenues for them to remain, and pursue more inclusive policies which expand access for Syrian refugees and host communities to critical services. In exchange for these commitments, donors, particularly the United States and EU, should provide a new package of support to fund local integration and drastically expand resettlement. Left with a choice between dire circumstances in their host nations or an unsafe return to Syria, many refugees may opt for uncertain paths, searching for a glimmer of hope elsewhere.

Featured Image: Syrian mother Shawafa Khodr holds a photograph of her daughter who went missing at sea off the coast of Lebanon, May 4, 2022. Photo by Delil Souleiman/AFP via Getty Images.