Human Rights in Southeast Asia: The Rohingya Crisis in Focus

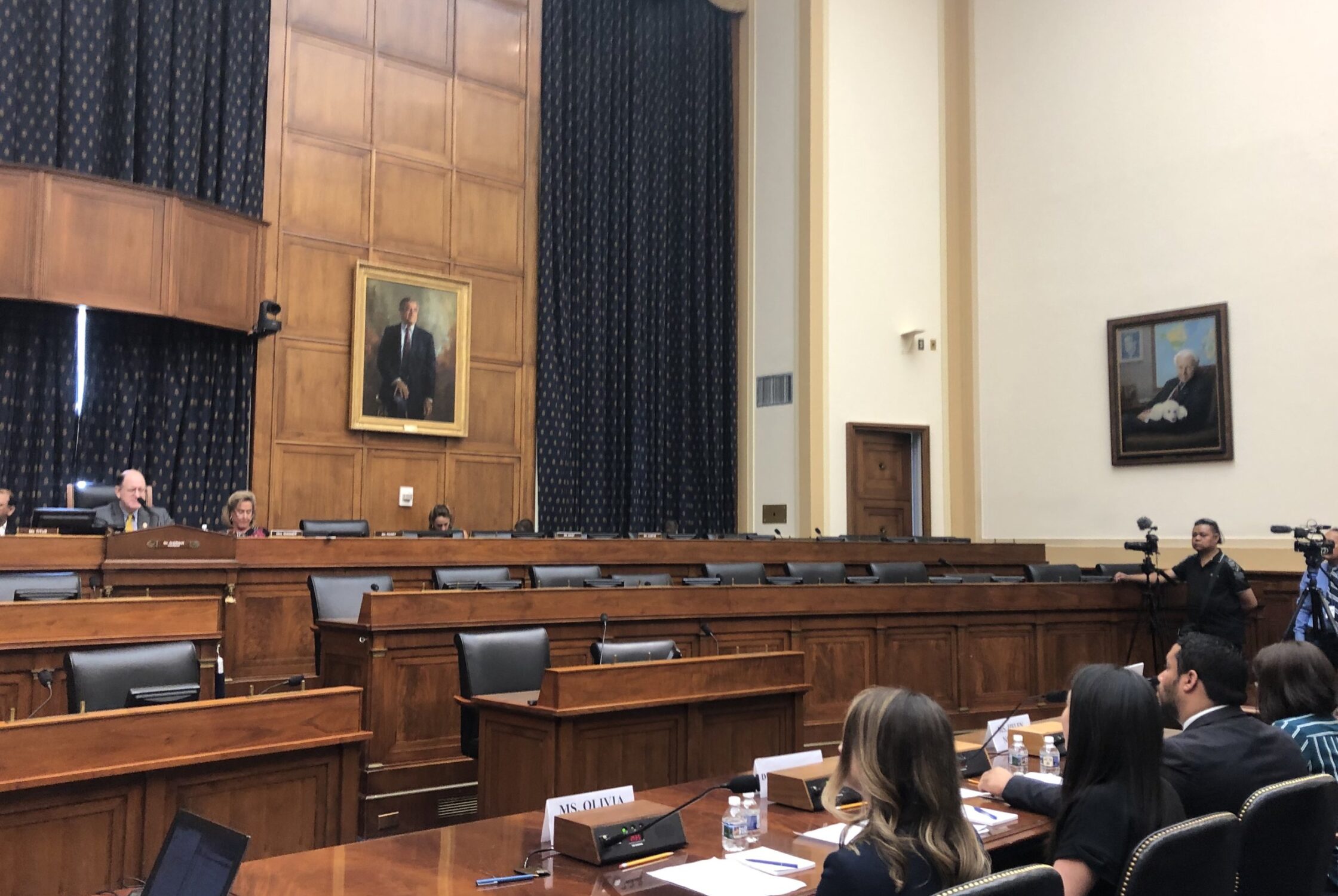

Testimony of Cindy Huang

Vice President of Strategic Outreach, Refugees International

House Committee on Foreign Affairs

Subcommittee: Asia, the Pacific, and Nonproliferation

“Human Rights in Southeast Asia: A Regional Outlook”

July 25, 2019

Watch the hearing here.

Chairman Sherman, Ranking Member Yoho, and distinguished members of the subcommittee,

Thank you for holding this timely hearing on human rights in Southeast Asia. I will be discussing today the plight of the Rohingya people, a long persecuted and stateless population. I visited the camps in Bangladesh last week and saw firsthand the urgent need for increased international support and diplomatic engagement.

Refugees International is a non-profit, non-governmental organization that advocates for lifesaving assistance and protection for displaced people in parts of the world impacted by conflict, persecution, and forced displacement. Based here in Washington, we conduct fact-finding missions to research and report on the circumstances of displaced populations in countries such as Somalia, Iraq, Bangladesh, and Syria. Refugees International has been reporting on the Rohingya population for many years on topics such as host country conditions, protection measures for women and girls, and humanitarian and human rights considerations. Refugees International does not accept any government or United Nations funding, which helps ensure that our advocacy is impartial and independent.

One month from today, August 25th, will mark the two-year anniversary of the mass violence that led more than 700,000 Rohingya Muslim people to flee Myanmar across the border into Bangladesh. Ten days after the violence began, Refugees International determined and publicly declared that crimes against humanity were taking place, findings that were later confirmed by many others—including an independent UN fact-finding mission in 2018. That mission also called for military leaders to be investigated and prosecuted for genocide.[1] It found the military conducted clearing operations and other planned activities that extended far beyond the immediate response to the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army attacks on police and military outposts. The State Department’s own report supported these findings but fell short of making a legal determination on whether crimes against humanity and genocide took place. A senior UN official called the situation a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”[2] Bangladesh is now hosting a total of more than a million Rohingya refugees. An estimated 520,000 to 600,000 Rohingya remain in Rakhine State, Myanmar.[3] Of these, 126,000 live in camps for internally displaced people (IDPs) that were established following a crackdown against the Rohingya in 2012. The UN has called the conditions in the camp “deplorable.”[4] A significant number of Rohingya refugees live in other countries in the region, including Malaysia, Pakistan, and India, where many face serious protection concerns.

The numbers displaced and their conditions speak to Myanmar’s decades-long efforts to persecute and exclude Rohingya. A turn for the worse came with the passage of the 1982 citizenship law that excluded Rohingya and several other ethnic minorities. This accelerated an already deteriorating situation for the Rohingya—including denial of basic access to healthcare and education, vulnerability to arbitrary arrest and forced labor, and restrictions on movement, marriage, and children. Alongside these trendlines, episodes of disproportionate violence have caused widespread suffering and displacement.

The hopeful news is that much more can be done to seek accountability for crimes in Myanmar and promote conditions for sustainable return and protection of Rohingya communities. In interviews last week in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, I heard repeatedly that Rohingya look to the United States for leadership. Many receive news of related Congressional hearings, such as this one, and they are closely following U.S. engagement, such as the recent announcement of a travel ban on Myanmar’s top generals.

But actions to date have failed to spur meaningful progress. For instance, it is puzzling and frustrating that the administration has failed to declare that the Myanmar military is responsible for crimes against humanity, as there is overwhelming evidence that such crimes have been committed. The recent sanctioning of Senior General Min Aung Hlaing is significant, but sanctions should go beyond a travel ban to include targeted financial sanctions on Myanmar generals and military-owned enterprises. Many Rohingya and advocates, like myself, were heartened that Rohingya leader Mohib Ullah was invited to participate in last week’s Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom. But we were disappointed when President Trump did not seem familiar with key details of these mass crimes.[5]

In fact, we are not aware of any public statements made by the president about the atrocities committed against the Rohingya. This is disappointing as the United States can and should lead a global effort to pursue a just and sustainable solution for the Rohingya people. But this can only be successful if leadership comes from the highest levels of the administration and Congress. And while senior administration officials make statements about the crisis from time to time, there is no evidence of a concerted high-level diplomatic campaign of the kind that would be necessary to create real change.

Deteriorating conditions in Rakhine State, dim prospects for return

It is of utmost concern that conditions in Rakhine State continue to deteriorate. Another dimension of the situation separate from the Rohingya is the struggle between the Myanmar government and the Arakan Army, an armed group from the ethnic Rakhine Buddhist community. In early 2019, the Arakan Army conducted coordinated attacks on police stations. Myanmar security forces responded with a crackdown that led to displacement of 30,000 ethnic Rakhine and others in the region.[6] Citing continued fighting in Rakhine, the government shutdown the internet in parts of Rakhine in late June. The UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee called the ongoing blackout “unprecedented and unacceptable,” noting that the government is blocking information, a warning sign of potential atrocities, and hampering humanitarian relief efforts among Rohingya, Rakhine, and other communities.[7]

Beyond these recent counterproductive measures, the Myanmar government has failed to make progress on human rights, protection, and conditions for the safe, dignified, and sustainable return of Rohingya refugees to Rakhine. For the several hundred thousand Rohingya who are still in Rahkine, the conditions are horrific. They face systematic and state-sponsored discrimination and segregation, including severe restrictions on freedom of movement and access to essential health and education services, and other violations including arbitrary arrests, sexual violence, and forced labor. In February and April 2019, Refugees International advocates interviewed refugees in Bangladesh, including those who had recently fled Myanmar and who described the terrible conditions firsthand.[8] For example, Noor Jan, a 70-year-old Rohingya refugee described security forces coming to her village almost every night, beating people, or taking men for forced labor or women to be sexually assaulted.

For those living in IDP camps in central Rakhine, which are essentially open-air prisons, the Myanmar government is moving forward with a plan to close the camps, ostensibly to improve conditions for the displaced. However, the closure of some IDP camps to date has resulted in superficial changes, such as shifting people to structures next to camps, without any increase in freedom of movement, access to non-segregated services and livelihoods, or opportunity to return to their lands.[9] In some cases, IDP villages of origin in central Rakhine have been built over for other use, extending the pattern of deliberate destruction observed in northern Rakhine. Restrictions on movement remain severe, affecting not only IDPs but also non-displaced Rohingya who cannot use roads due to the deliberate placement of checkpoints near villages. Arbitrary imprisonment and detention in dangerous conditions remain the reality for hundreds of Rohingya.

Most fundamentally, the question of citizenship remains outstanding. The Myanmar government continues to pursue the National Verification Card (NVC) process, which offers Rohingya temporary residence and a purported opportunity to be considered for citizenship later. However, this is based on the discriminatory 1982 Citizenship Law that requires Rohingya to renounce their identity as a distinct ethnic group. As a refugee in Bangladesh told the Refugees International team, “The NVC is the first step toward making us a foreigner.” The few thousand Rohingya who have undergone the NVC process still face significant restrictions in movement and livelihoods.

In light of these conditions, it is no surprise that Rohingya in Bangladesh refused to participate in the repatriation exercise in November 2018. In fact, Rohingya continue to flee to Bangladesh, including 946 between January and April 2019.[10] Despite rhetoric to the contrary, Myanmar’s government has demonstrated a complete lack of political will to create conditions that enable Rohingya to live with basic rights and dignity in Rakhine. In fact, they are actively pursuing policies that are making conditions worse.

Progress in Bangladesh, but near and medium-term challenges remain

The Bangladesh government must be commended for hosting more than a million refugees and continuing to allow Rohingya to seek refuge within its borders. Both the government and the international community should be proud of an effective humanitarian response in unprecedented circumstances. As the largest donor, the United States is supporting life-saving nutrition, food, health, water, sanitation, and other programs.[11] More than 300,000 Rohingya have been registered through the UNHCR-Government of Bangladesh process, providing their primary or only identity document that gives access to services and protection against forced return.[12] There was recent progress in education, with the Bangladesh government approving the first two of four levels of an informal learning framework. Critically, donors are also investing to improve the lives of host communities to address impacts, such as deforestation, and mitigate social tensions.

Despite these achievements, Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh continue to face steep challenges. The 2019 Joint Response Plan (JRP) for Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis has been funded at just a third of what is required to meet refugee and host needs.[13] In July, monsoons have displaced 6,000 refugees in the camps and killed two people.[14] Refugees remain vulnerable to food insecurity, and many resort to borrowing money or buying food on credit when their monthly assistance runs out.[15] Between July 2018 and July 2019, Rohingya households reported sharp increases in safety concerns for boys related to violence within the community (from 27 to 52 percent) and fears of kidnapping of girls (from 38 to 52 percent).[16] While progress has been made on providing gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health services, major challenges to scale and quality remain,[17] and the JRP estimates that 6,555 women and girls are at risk of sexual violence during 2019.[18] Space is a significant constraint that limits access to health, informal education, and other services. For example, many children attend informal education for only two hours to allow for multiple shifts per day. In the near-term, many issues could be partly addressed through policies that enable the construction of more semi-durable structures (including two-story ones), multipurpose cash assistance, and expanded cash-for-work opportunities.

As Refugees International has stated, Myanmar bears ultimate responsibility for addressing the root causes of the crisis and creating sustainable solutions. However, given the lack of progress to date, the reality is that most or all Rohingya will remain in Bangladesh for the foreseeable future. For this reason, the government of Bangladesh should reduce barriers that have impeded the effective delivery of humanitarian aid. As has been reported by Refugees International, it should establish clear and consistent guidance for NGO registration, project approvals, and visas.[19] More fundamentally, the Bangladesh government should recognize that the Rohingya are refugees with accompanying rights—including access to justice, health services, cash and livelihoods, and education, as well as freedom of movement—and allow aid organizations to provide these types of services. In fact, we believe the government of Bangladesh would be well advised to go further by considering opportunities for medium-term planning and investment that would create new job and livelihoods opportunities for refugees and hosts.[20] Evidence indicates that such an approach can mitigate social tensions and facilitate sustainable return when conditions exist by helping refugees develop portable skills and assets.[21] As opposed to relying on annual humanitarian aid that falls over time, this approach can generate substantial international financing and other support (e.g., trade concessions and investment facilitation) that advance outcomes for refugees, hosts, and sustainable development in Bangladesh.

In the immediate term, a major area of concern is the Bangladesh government’s plan to relocate 100,000 Rohingya to a Bhasan Char, a small island in the Bay of Bengal. The island, composed of silt, is vulnerable to cyclones and flooding and is a several hour boat ride from the mainland. As recently as last week, the government insisted that Rohingya will move to the island in the next few months, while underscoring that any relocations would be voluntary.[22] However, many questions remain about safety, access to services and livelihoods, and movement between the camps and island. In light of unanswered questions, the government should refrain from moving Rohingya to Bhasan Char.

Priorities for sustainable progress and way forward

The final report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, accepted by the Myanmar government, contains the key pillars necessary (if not sufficient) for a sustainable solution.[23] These include, but are not limited to, socio-economic development that benefits local communities; revisiting the citizenship law to align with international standards; freedom of movement for all people in Rakhine; and promoting communal representation and participation of underrepresented groups, including ethnic minorities, stateless, and displaced communities. Although the report was released just before the August 2017 wave of violence, its recommendations remain ever more relevant in light of worsening conditions.

While there has been some coordinated action, much greater progress can be achieved if the United States leads and mobilizes a global response. To support this, the United States should create a high-level envoy, with the support and confidence of the president, to work with governments and multilateral organizations to lead international efforts to end abuses, provide assistance and protection for Rohingya refugees and IDPs, and promote conditions for eventual safe and voluntary return of Rohingya to Myanmar.

The United States should forge a three-pillar plan to:

1. Increase international pressure on Myanmar toward justice, accountability, and conditions for return

- Make a legal determination, through the U.S. Secretary of State, as to whether the abuses identified in the U.S. State Department’s August 2018 report amount to crimes against humanity and genocide (or provide sufficient information to merit investigation and prosecution of senior officials for genocide).[24]

- Continue to pursue enactment of legislation, such as the bipartisan Burma United through Rigorous Military Accountability (BURMA) Act of 2019 advanced by your committee last month—or similar language as an NDAA amendment, as was recently passed by the House. I wish to thank the subcommittee members who cosponsored the BURMA Act, which would limit security assistance until impunity for human rights abuses ends and impose visa and financial sanctions on military leaders responsible for serious human rights abuses.

- Building on the targeted travel sanctions on Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and three others, impose additional travel and financial sanctions on high-level Myanmar military officials as identified in the UN Fact-Finding Mission report, as well as the leadership of military-owned enterprises.

Lead a high-level international diplomatic campaign to advance accountability and sustainable solutions, including efforts to:

- Establish an ad hoc tribunal or referral to the International Criminal Court.

- Demand access for the UN Fact-Finding Mission and the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Myanmar, and support the transition from the mission to the UN-sponsored Independent Investigative Mechanism for collecting evidence related to atrocity crimes committed against the Rohingya.

- Demand access for and inclusion of UN agencies in any plans to repatriate Rohingya to Myanmar.

- Place a multilateral arms embargo on the Myanmar military until those responsible for atrocity crimes are held to account.

- Implement recommendations of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, including those related to socio-economic development, citizenship, and freedom of movement.

2. Elevate and ensure Rohingya participation in all related forums and processes.

- As reflected in the 2019 Joint Response Plan for Rohingya Humanitarian Response, ensure robust participation of Rohingya throughout the response in Bangladesh, including through the creation of youth, men, and women committees.

- Encourage the Bangladesh government to enhance engagement with Rohingya groups to understand their needs and priorities, as well as their concerns about premature repatriation.

- Support the representation of Rohingya refugees in regional and global forums on the Rohingya crisis and consult and inform refugees on UN agreements, including those related to repatriation.

3. Increase support for Bangladesh and encourage the government of Bangladesh to support measures that enhance Rohingya and host wellbeing

- Maintain generous support for the humanitarian response and scale up investments for host communities.

- Encourage the Bangladesh government to permit the assistance necessary to meet humanitarian needs, and to begin dialogue on broader refugee and host needs that would arise in the context of protracted displacement.

Lead international efforts, including those to:

- Fully fund the JRP activities for Rohingya refugees and host communities.

- Oppose the relocation of Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char in light of ongoing questions and concerns that have not been addressed.

- Advocate for near-term policy shifts that would facilitate improved refugee wellbeing and security, such as increasing multipurpose cash assistance, cash-for-work opportunities, semi-durable structures, and community policing.

- Support a curriculum for Rohingya refugee children that aligns with national standards and provides a path for future certification.

- Support a medium-term development plan for Cox’s Bazar that includes opportunities for improved skills, livelihoods, and self-reliance for both hosts and refugees.

- Encourage the World Bank, as well as the Asian Development Bank, to scale up its investments in Cox’s Bazar and support a coordinated policy dialogue.

By pursuing these actions, the United States can play a decisive role in advancing Rohingya rights and promoting regional stability. At a time when human rights and refugee rights are increasingly under attack, standing up for the Rohingya people sends a critical message about our values and priorities. Thank you again for the opportunity to testify today.

Endnotes

[1]Myanmar: UN Fact-Finding Mission releases its full account of massive violations by military in Rakhine, Kachin and Shan States. OHCHR, 2018. (https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/Pages/NewsDetail.aspx?NewsID=23575&LangID=E)

[2]UN human rights chief points to ‘textbook example of ethnic cleansing’ in Myanmar, UN News, September 11, 2017. (https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/09/564622-un-human-rights-chief-points-textbook-example-ethnic-cleansing-myanmar)

[3]2018 Report on International Religious Freedom: Burma. U.S. Department of State, 2019. (https://www.state.gov/reports/2018-report-on-international-religious-freedom/burma/) Estimates vary widely, in large part due to lack of access to Rohingya populations in Myanmar.

[4]Myanmar Humanitarian Brief.OCHA, 2018. (https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/OCHA%20Myanmar%20Humanitarian%20Brief%20-%20September%202018.pdf)

[5]A Yazidi woman from Iraq told Trump that ISIS killed her family. ‘Where are they now?’ he asked. The Washington Post, 2019. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/a-yazidi-woman-from-iraq-told-trump-that-isis-killed-her-family-where-are-they-now-he-asked/2019/07/19/cc0c83e0-aa2d-11e9-a3a6-ab670962db05_story.html?utm_term=.1c275d3dfd57)

[6]“No one can protect us” – War crimes and abuses in Myanmar’s Rakhine state.Amnesty International, 2019. (https://www.amnestyusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Briefing-Myanmar-No-one-can-protect-us.pdf)

[7]Myanmar: Internet Shutdown Risks Lives.Human Rights Watch, 2019. (https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/28/myanmar-internet-shutdown-risks-lives)

[8]Abuse or Exile: Myanmar’s ongoing persecution of the Rohingya.Refugees International, 2019. (http://www.refugeesinternational.org/s/Bangladesh-FINAL.pdf)

[9]Erasing the Rohingya: Point of No Return.Reuters, 2017. (https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/myanmar-rohingya-return/)

[10]Operational Dashboard: 2019 Indicators Monitoring.UNHCR, 2019. (https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/70378)

[11]Bangladesh: 2019 Joint Response Plan for Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis (January-December).Financial Tracking Service, 2019 (https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/719/summary).

[12]Operational Update: Bangladesh. UNHCR, 2019. (https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/69927)

[13]Heavy monsoon rains drench Rohingya sites in Bangladesh.UNHCR, 2019. (https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2019/7/5d1f08404/heavy-monsoon-rains-drench-rohingya-sites-bangladesh.html)

[14]Bangladesh: Rohingya face monsoon floods, landslides.Human Rights Watch, 2019. (https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/12/bangladesh-rohingya-face-monsoon-floods-landslides)

[15]The Rohingya: Displacement, Deprivation and Policy. International Food Policy Research Institute, 2019. (http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/133324/filename/133535.pdf)

[16]Multi-Sector Needs Assessment II – All Camps. UNHCR-REACH, 2019. (https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/68613.pdf)

[17]Still at Risk: Restrictions Endanger Rohingya Women and Girls in Bangladesh.Refugees International, 2018. (http://www.refugeesinternational.org/s/Bangladesh-GBV-Report-July-2018-final-rfbt.pdf) & Removing Barriers and Closing Gaps: Improving Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for Rohingya Refugees and Host Communities.Center for Global Development, 2019. (https://www.cgdev.org/publication/removing-barriers-and-closing-gaps-improving-sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights)

[18]2019 Joint Response Plan for Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis. IOM, UNHCR, UNRC Bangladesh, Inter Sector Coordination Group, 2019. (https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2019%20JRP%20for%20Rohingya%20Humanitarian%20Crisis%20%28February%202019%29.compressed_0.pdf)

[19]Aid Restrictions Endangering Rohingya ahead of Monsoons in Bangladesh. Refugees International, 2018. (https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports/rohingyalivesatrisk)

[20]Toward Medium-Term Solutions for Rohingya Refugees and Hosts in Bangladesh: Mapping Potential Responsibility-Sharing Contributions.Center for Global Development, 2019. (https://www.cgdev.org/publication/toward-medium-term-solutions-rohingya-refugees-and-hosts-bangladesh-mapping-potential)

[21]Sustainable Refugee Return: Triggers, constraints, and lessons on addressing the development challenges of forced displacement.World Bank Group, 2015.

[22]Bangladesh prepares to move Rohingya to island at risk of floods and cyclones.The Guardian, 2019. (https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/jul/19/bangladesh-prepares-to-move-rohingya-to-island-at-risk-of-floods-and-cyclones)

[23]Towards a Peaceful, Fair and Prosperous Future for the People of Rakhine.Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, 2017. (http://www.rakhinecommission.org/the-final-report/)

[24]Many of these recommendations are also included in Abuse or Exile: Myanmar’s ongoing persecution of the Rohingya. Refugees International, 2019. (http://www.refugeesinternational.org/s/Bangladesh-FINAL.pdf)