New Zealand’s ‘Climate Refugee’ Visas: Lessons for the Rest of the World

The New Zealand example, while well-intentioned, shows that developed countries cannot and should not merely skip to the end result.

In October 2017, New Zealand’s (then) new minister for climate change, James Shaw, announced that the country was considering issuing “an experimental humanitarian visa” category for Pacific Islanders displaced by the effects of climate change. The new scheme would aim to bring around 100 people a year to New Zealand. “We are anchored in the Pacific,” Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said. “I see it as a personal and national responsibility to do our part.”

The “climate refugees” announcement spread around the world, with many praising the new Labour government for such a bold and necessary move. And yet, just six months later, the plan was dropped. Why? And what lessons does this move hold for other regions of the world affected by rising human mobility due to climate change?

How should we respond to human mobility due to climate change?

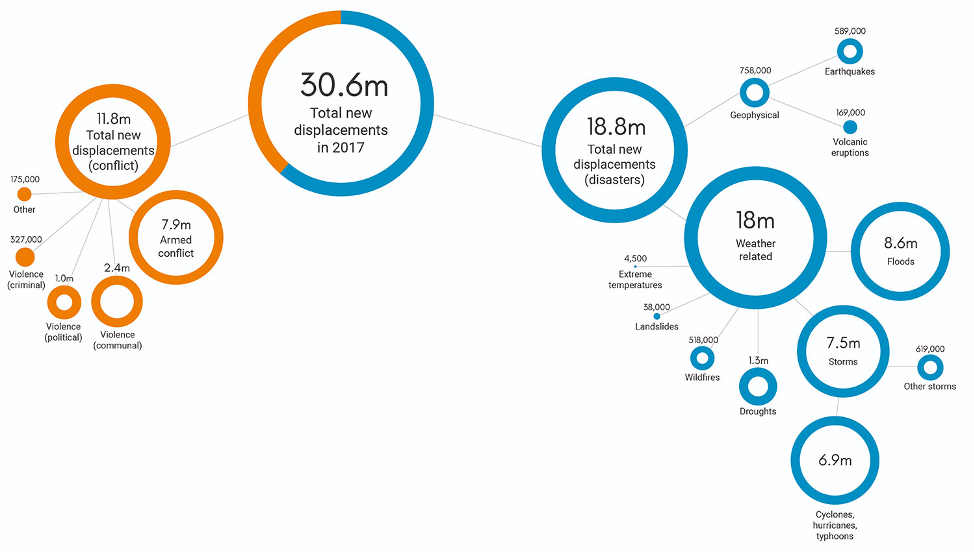

The link between climate change and human mobility is complex. We know that climate change is altering the frequency, intensity, duration, timing, and location of sudden- and slow-onset climate-related hazards. These hazards have caused extensive humanitarian needs and forced people to move both internally and outside their own borders. The data on movement due to sudden-onset hazards, like typhoons and floods, is clearer. In 2018, 18.8 million new people were displaced by these disasters, more than by conflict. But we don’t know how many people will need to move due to slow-onset hazards, like drought or desertification. The World Bank estimates that around 143 million people across sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America will move internally due to these hazards by 2050.

Figure 1. 61 percent of all internal displacements in 2018 were due to natural disasters

If global temperatures continue to rise, and slow- and sudden-onset hazards increase, we can expect to see a rise in human mobility. A recent article in Science projected this could increase asylum applications in the European Union by 28 percent by end of the century. Despite this, there is currently no international agreement on how these people should be protected. The 1951 Refugee Convention, which provides grounds for refugee status, does not cover those displaced due to climate hazards. On the one hand, some argue the Convention is outdated and should be revised to take into account new global challenges like climate change. On the other are a number of arguments as to why it shouldn’t, such as the aforementioned murky nature of the issue, the political difficulty of a negotiation, and the ensuing financial and administrative burden. Maybe, instead, we should be calling them “climate migrants,” using existing migration management instruments and policies, and new ones like the recently agreed Global Compact for Migration.

Regardless of the term used, policymakers have long debated the need for national and international policies governing human mobility due to climate change. Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), human mobility is dealt with by two different but complementary frameworks: adaptation and loss and damage (compensation for climate change impacts that exceed adaptation limits). In 2015, at the 20th session of the Conference of Parties to the UNFCCC (COP 20) in Lima, Peru, the idea of a “Climate Change Displacement Coordination Facility” was floated, which would provide emergency relief; assist in providing organized migration and planned relocation; and undertake compensation measures. However, mention of such a facility was struck from the text during negotiations at COP 21 in Paris, France, and the recent COP 25 in Madrid, Spain failed to provide new support for loss and damage, let alone a displacement facility.

While the debate about climate change impacts seems settled, policy options are decidedly less so. Given this, what should developed countries be doing? Should there be a new international policy? Many national ones? Financial support? New visa frameworks? Or something else entirely?

What do affected people actually want?

New Zealand dropped its plan to issue “climate refugee” visas for one crucial reason—Pacific Islanders didn’t want them. They saw gaining refugee status as a last resort. Instead, they called on the New Zealand government to institute a step-wise approach: reduce emissions, support adaptation efforts, provide legal migration pathways, and finally, if all fails, grant a form of legally protected status.

Reduce emissions

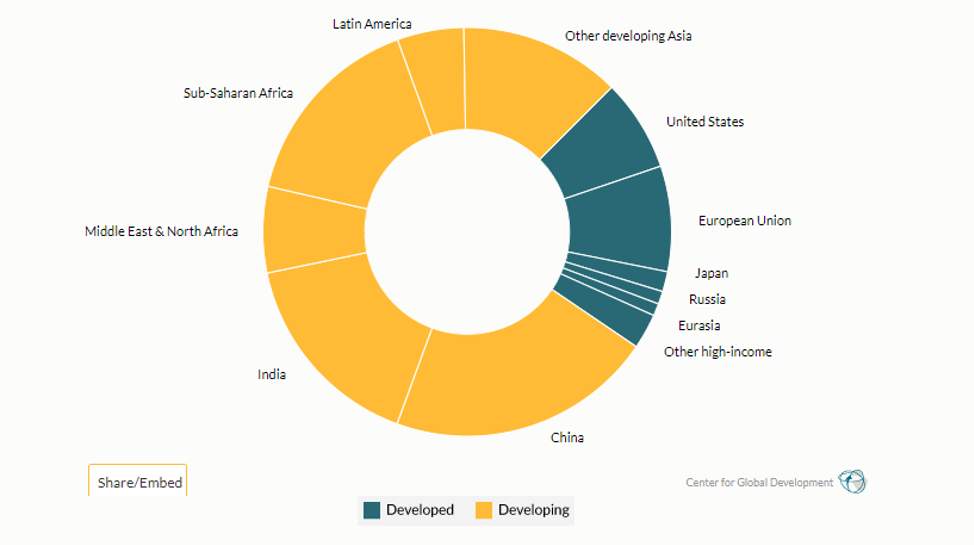

Firstly, Pacific Islanders called on New Zealand (and, by proxy, all developed countries) to not make the problem any worse. Historically, developed countries have produced the majority of emissions, and today, developing countries are disproportionately suffering. To hold the global average temperature increase to 1.5°C net, CO2 emissions need to drop 45 percent from their 2010 levels by 2030, and reach net-zero by 2050. Even if we manage this feat, by 2100 the world will still see a 48cm sea level rise, 135.2 million people exposed to severe drought, and reductions in crop yields (to name just a few impacts). As illustrated at COP 25, today’s policy context makes it difficult to imagine even being able to hold at this level of emissions. Policymakers must accept that adaptation will be necessary.

Figure 2. In 2015, developing countries shoulder 78 percent of the cost of climate change

Support adaptation efforts

Secondly, Pacific Islanders want help to stay in their homelands. Many, especially indigenous people, see migrating as a disruption of ancestral livelihoods and cultural loss. Instead, they want developed countries to support developing countries to adapt to climate change. This adaptation will not come cheap: estimates range from US$140 – US$300 billion needed per year. In 2016, only US$22 billion was provided. Efforts like the World Resources Institute’s “Adaptation Finance Accountability Initiative,” which tracks financial flows and supports civil society efforts to participate in adaptation finance decisions, may help with the funding problem. What to spend it on is another issue.

There are many adaptation options that may enable people to stay, such as providing more drought- or flood-resistant crops and/or access to alternative livelihoods outside of agriculture, but the right response depends on the context and what is “driving” displacement. It may be more helpful to start with the principle that movement will be likely (and necessary in some cases), so what would adaptation in a highly mobile world look like? Realistically, adaptation means investing in disaster risk reduction (DRR) efforts and urban planning for megacities and secondary cities, which will see high rates of migration. It also means ensuring that existing social protection measures are mobile, so that access is continuous and less onerous.

Provide legal migration pathways

Thirdly, if it is necessary for people to move, Pacific Islanders called on developed countries to provide “opportunities to migrate with dignity,” avoiding the stigma of being “refugees” per se. This will require the creation of three complementary pathways: bilateral/regional labor migration opportunities, humanitarian visas, and planned relocation/managed retreat.

On the first, Australia and New Zealand are already world leaders in providing labor migration opportunities to low-, medium-, and high-skilled workers from across the Pacific. Seasonal Worker Programs in Australia and New Zealand have formalized and extended the informal, and sometimes illegal, schemes of the past, and are a first step towards an integrated “skilled” labor market in the region. Institutions like the Australia Pacific Training Coalition (APTC) provide Pacific Islanders with Australian-recognized qualifications based on skills needs in both countries. These are excellent models on which to build—giving Pacific Islanders the ability to move safely and in a way that benefits all parties involved, without waiting for the impacts of climate change to take even greater hold. The design and execution of these schemes also provides a tried and tested way to promote low- and semi-skilled labor migration in other regions of the world. For example, the United Kingdom could mitigate the impact of climate change in Bangladesh by providing locals with training and migration opportunities.

On the second, governments need to open and expand humanitarian visas. There’s an opportunity in extending existing mechanisms, such as the US “Temporary Protected Status” scheme or Brazil’s “humanitarian visas,” which have already provided safe pathways for Haitians and Syrians. These schemes would facilitate free movement immediately after a disaster, although for a time-limited period. Recently, there has been a surge in interest in creating new visa schemes entirely, as is the case for a landmark bill introduced by Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) to welcome up to 50,000 “climate-displaced persons” every year.

On the third, we need to be realistic that unless we cut emissions dramatically and rapidly, some form of internal planned relocation/managed retreat will be necessary. In fact, a recent study finds that we have been severely underestimating the amount of sea-level rise, predicting that some 150 million people are now living on land that will be below the high-tide line by 2050. Here, planning proactively and with community buy-in is the only sensible way forward. Again, the Pacific Islands are world-leaders in this respect. Fiji has agreed to National Relocation Guidelines that provide guidance for both the government and communities affected by slow- and sudden-onset hazards. And Vanuatu’s Ministry of Climate Change Adaptation has prepared a National Policy on Climate Change and Disaster-Induced Displacement, which aims to ensure “movement takes place with dignity and with appropriate safeguards and human rights protections in place.”

Grant “refugee” status

And finally, if the above efforts fail, a legally protected status may need to be provided. The New Zealand government acknowledged that if global emissions targets were missed and rising ocean levels threatened the islands, the issue may “take on greater urgency.” Given the expert views discussed above, amending the 1951 Refugee Convention to include “climate refugees” may be more trouble than it’s worth. However, to provide comprehensive and rights-respecting support, the world will need something with the same amount of recognition and impact. As mentioned above, humanitarian visas may fill the gap partially. However, as current politics show these may be on the chopping block if less sympathetic leaders are in charge. Existing iterations of humanitarian visas need to strengthened, with very real advantages to creating pathways towards citizenship, for example. Various other policy options have been well discussed in other documents, so we will not repeat them here. Suffice to say, developed countries will need to step up—providing more routes if all else fails.

In the next 30 years, hundreds of millions of people will be affected by slow- and sudden-onset hazards, brought about by climate change. Most of these people are currently living in developing countries and lack the support to adapt to their changing environment. The New Zealand example, while well-intentioned, shows that developed countries cannot and should not merely skip only provide “climate refugee” status. They must do everything in their power to reduce emissions, support adaptation efforts, and promote legal migration pathways. This is what those affected want, and what will make the biggest positive impact on the world as a whole.

This piece was originally published on the Center for Global Development’s website.