“It’s a Suicide Act to Leave or Stay”: Internal Displacement in El Salvador

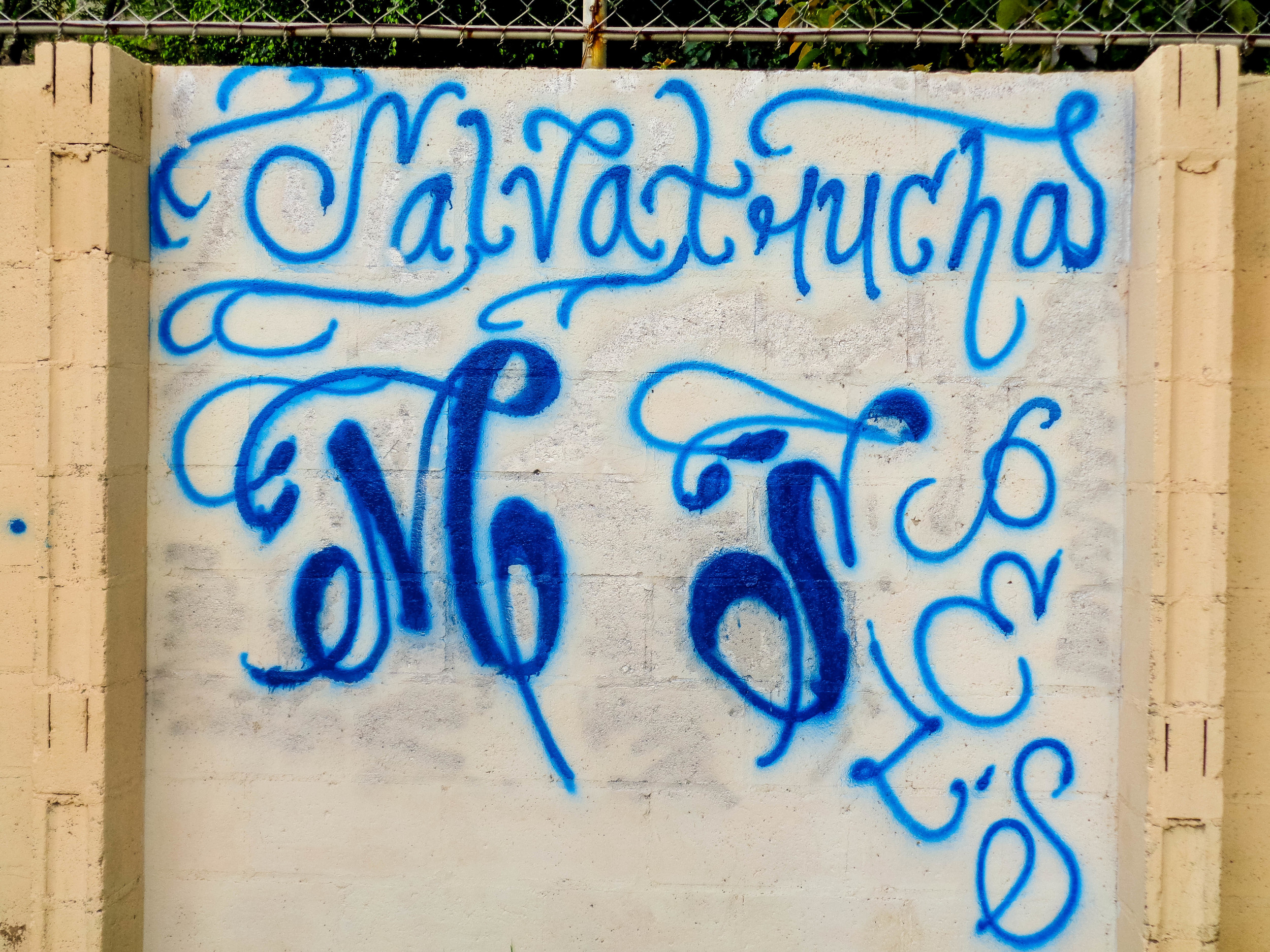

El Salvador has just achieved the grim distinction of becoming the murder capital of the world. In the first six months of this year, almost 3,000 people were murdered, and hundreds of thousands more were subject to extortion, death threats, forced recruitment, and rape by the country’s two major gangs.

So far, the government has been unable to stop this extraordinary level of violence, which is forcing tens of thousands of Salvadorans from their homes. The government is unwilling to acknowledge that gang activity is responsible for this forced displacement. However, neighboring countries are well aware of the consequences of this violence, as tens of thousands of Salvadorans are arriving at their borders requesting protection. El Salvador needs to implement a comprehensive national humanitarian strategy to respond to and assist the forcibly displaced. Until such a strategy is implemented, Salvadorans will continue to seek refuge outside the country.

Background

El Salvador’s brutal civil war officially concluded in 1992, but many Salvadorans say that the violence never really ended. This perspective is understandable. While 75,000 people were killed during the 12 years of civil war, more than 100,000 Salvadorans have died violently in the 20 years since. With a population of just over 6 million people and a size no bigger than Massachusetts, El Salvador is one of the deadliest countries in the world. More children are killed in El Salvador per capita than in any other country.

“In the past, once the gangs found people, they would threaten them. Now they just kill them.”

Municipal officer, San Salvador

The El Salvador government has not admitted formally that Salvadorans are being forcibly displaced by gangs – preferring to say instead that people are leaving the country for economic reasons or to be reunited with family. While certainly some Salvadorans are moving for these reasons, according to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), human rights, academic, and government reporting on asylum requests, massive numbers of Salvadoran youth and adults do not make the choice to leave their homes but are instead forced out. El Salvador has the highest concentration of gang members per capita in Central America, and there is also a large presence of narco-traffickers originating from Mexico. In 2013, UNHCR concluded that 66 percent of all unaccompanied Salvadoran children had fled to escape abuse by criminal actors.

They are killed because they live in communities that have been overtaken by gangs, or they are young women unwilling to submit to sexual assault or other violence meted out by gang members, or they are presumed to be gang members due to their youth or presentation and thus they are killed extra-judicially by the police or military. Sometimes gangs target a home or an apartment building simply because of their strategic locations, and once ordered out residents have no alternative but to leave. All of this happens with almost complete impunity, and it is driving forced displace- ment. In June, an RI team went to El Salvador to learn more about why people are being forcibly displaced and how the government is responding to their humanitarian needs. While there, the team met with one activist who said, “During the war we had more support because there was a big response to the needs of refugees and IDPs (internally displaced people). Now it’s each for his own.”

Recommendations

The El Salvador government should:

- Publicly acknowledge that gangs and some police and military actors are causing internal and external displacement from El Salvador and commit to developing and implementing a humanitarian response;

- Appoint the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office (PDDH) as the lead and institutional focal point on internal displacement issues within the National Council of Citizen Security and Coexistence, and establish an interdepartmental working group for coordinating humanitarian responses;

- The interdepartmental working group should include representatives from the National Institutes on Women and Children, Ministries of Housing and Education, municipal and departmental counterparts, and civil society organizations (CSOs);

- Within 12 months, the interdepartmental working group should establish a funded and functioning internally displaced person (IDP) protocol that includes a comprehensive profiling procedure and is prepared to assist IDPs with protection, shelter, documentation, education, and health care;

- Build transitional centers that provide forcibly displaced families with temporary shelter to consider next steps, and include access to legal assistance, health and psychosocial care, and expedited acquisition of birth certificates and national identifications;

- With support from the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), consult with municipal governments in all of El Salvador’s 14 departments to identify possible family relocation and resettlement sites, and ensure that planning takes into account both the concerns of host communities and the specific protection and livelihood needs of displaced families; and

- Add specific questions to the 2017 national census that facilitate the collection of data on how many people have fled their homes due to violence, where they have relocated, and the demographics of their households.

The United States government should:

- Fund programs bilaterally and through regional agreements such as the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) and the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle (PAPNT) that permit the El Salvador government to develop and respond to the humanitarian and protection needs of those internally displaced by gangs;

- Provide grants through the U.S. Agency for International Development to emerging Salvadoran CSOs exhibiting the potential to effectively develop and deliver humanitarian assistance to IDPs inside El Salvador;

- Consistent with the 1980 Refugee Act and the UN Convention Against Torture, ensure that all adults and children arriving at the U.S. border who express a fear of serious human rights violations, persecution, or torture be given due process and the opportunity to articulate their fear of return before an asylum officer; and

- Reauthorize Temporary Protected Status for Salvadorans because the El Salvador government is temporarily incapable of receiving them due to the extraordinary levels of violence and insecurity in the country.

Governments in neighboring countries including Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama should:

- With the support of the UNHCR, ensure that all Salvadorans expressing a fear of serious human rights violations, persecution, or torture be given due process and the opportunity to articulate their fear of return before an officer authorized to adjudicate asylum applications consistent with the Refugee Convention, Cartagena Declaration and Brazil Plan of Action, and other complementary forms of protection.

Sarnata Reynolds traveled to El Salvador in June 2015 to assess the humanitarian situation of people internally displaced by gangs, in consultation with Foundation Cristosal, an independent nonprofit organization partnering with the people of El Salvador in their struggle for peace, justice, and reconciliation.